My motivation for writing this post comes from recent activity on Twitter about “coercive care” in psychiatry and an opinion posted there by a psychiatrist suggesting that psychiatrists need to be aware of their role as an agent of the state when they are engaged in involuntary treatment. After seeing this I checked the literature and there were papers published on the subject – so I thought I would write a post about the issue – specifically whether coercion is an appropriate word to use and how it compares to involuntary treatment as a description and a concept.

I don’t consider the issue lightly. For most of my career I have been in acute

care settings that required knowledge and skill in negotiating involuntary care

scenarios – specifically emergency holds, probate court holds, civil

commitments, conservatorships, and guardianships. That involved hundreds of

court appearances in 7 counties and 2 different states. I also testified as an expert on the issue of

prolonged state hospital stays for a patient advocacy organization and

testified in both malpractice cases and a criminal responsibility case. I have personally seen how local politics can

affect the civil commitment and conservatorship laws to the point that they are

actively ignored for various reasons. In that unstable landscape, the staff

responsible for treating the patient needs to be very flexible and innovative

to provide the necessary care. The

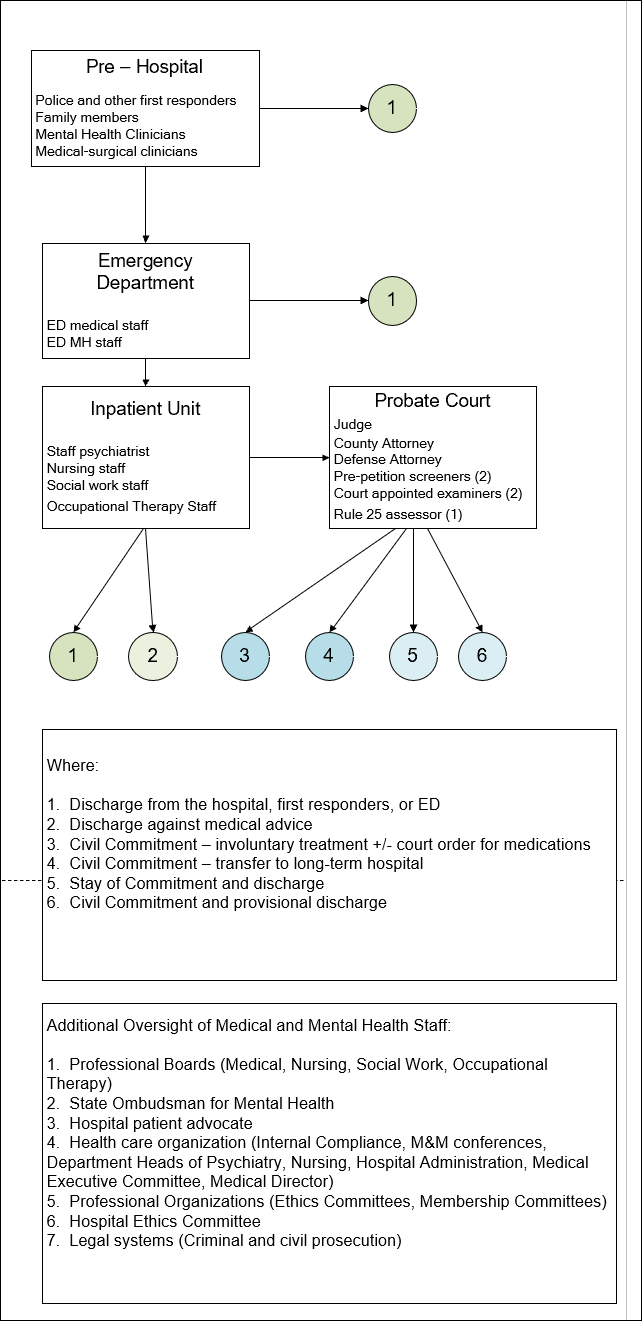

following graphics show what that care generally looks like. It is a diagram of how involuntary treatment

gets initiated and carried out.

The commonest path is that there is an incident in the

community, emergency medical services are activated, and the patient is placed

on a hold and transported to the emergency department (ED). While there an ED physician and mental health

clinician (typically a social worker) makes and assessment of the patient and

determines if they can be discharged, admitted on a voluntary basis, or

admitted on an emergency hold.

Following the admission, the inpatient staff makes their

respective assessments and typically discuss their findings and the plan in

team meetings. If the patient was admitted on a timed hold (72 or 96 hours) and

a determination is made that the patient cannot be treated on a voluntary basis

prepetition screeners are contacted.

They come in and see the patient and collect more collateral information

than the inpatient team has access to.

They compile this in a prepetition screening document and in a team

meeting separate from the hospital staff (they are typically county employees)

make a determination that the hold will be cancelled or they will refer the

patient for further court intervention. If

they determine to not support the emergency hold, the patient is typically

discharged and it is illegal for a physician to immediately place them on

another emergency hold. If they are referred to the court a probable cause

hearing is held. At that point the judge

can release the patient or refer for a final hearing. Before any final hearing, 2 court appointed

examiners (typically a psychiatrists or psychologists employed by the county)

will see and assess the patient. They will testify in court and give specific

treatment recommendations to the court – independent of the hospital staff

charged with treating the patient. At the final hearing the patient can again

be released with no court intervention based on a judge’s decision. They can

also be court ordered to follow treatment recommendations including further

hospitalization and medications. Courts

can also accept a stay of commitment – meaning that the patient is not formally

ordered to accept treatment for a duration of time but they can accept

treatment and follow up and if everything is going well at 6 months any

involvement with the court self dismisses.

There is a similar intervention for persons who have been formally

committed called a provisional discharge. In that case, the person is

discharged with a plan to report back on outpatient progress. The structure of

this process highlights the fact that no single person or discipline makes a

decision about involuntary treatment. In addition, the statutory requirements

for mental illness or substance abuse do not specify any particular diagnosis

but depend on whether there is behavior that is self-endangering, harmful to

others, or significantly affects the person’s ability to function in their own

interest at the most basic level (adequate self-care in terms of food, housing,

and addressing significant medical problems).

The question critical to this post is how is this process

coercive rather than involuntary? And is there a difference between those terms? Just looking at standard definitions coercion

is clearly more insidious and it implies malignant intent. The Webster’s

definition is “to compel by force or intimidation; to bring about by force; to

dominate or control esp. by exploiting fear, anxiety, etc.” Using the same source, the definition of

involuntary is “not voluntary, independent of one’s will.” At this level, coercion is nothing medical

staff are ever trained to do and in fact would constitute a violation of

professional ethics. In psychiatry, the

training is focused on helping psychiatrists overcome standard biases that

people experience when interacting with others who have clear problems with

severe psychiatric disorders. The entire

focus of psychiatric training is developing a cooperative and helpful

relationship.

What about legal definitions and statutes pertaining to

coercion? The legal definition of

coercion is essentially the same as the dictionary definition: Verbal and/or physical threats and other

forms of intimidation in order to force someone to do something/not do

something that they are otherwise legally allowed/not allowed to do. Laws against coercion in federal statues

range from the obvious forms like sex trafficking to threats of retaliation for

political activity or exercising rights at work. In all of these cases, the

victims of coercion are generally going to be capable of making decisions in

their best interest but are unable to make willful decisions due to coercion.

It turns out that an entirely different level of analysis

has been applied to the issue of coercion and psychiatric patients. That level

of analysis is done by philosophers using thoughts about coercion from previous

works on ethics. For example, Schramme (2)

expands arguments from Frankfurt’s work to discuss specific examples of

coercion. He begins with the informed consent model. I consider Gutheil and Appelbaum to be

authoritative in this area and they discuss three elements of informed consent:

information, voluntariness, and competence (3).

The adequate information is discussed from the perspective of a

professional level of disclosure and also a “reasonable person” or the level of

information that most people would expect. The expected information varies from

state-to-state and in some cases for psychiatry there is a written information

standard. For example, in the State of Minnesota, antipsychotic medication

consent requires a signed consent form about those potential side effects. Voluntariness means consent is freely

given. It is often assumed that since psychiatric patients are generally

considered to be vulnerable adults who may be dependent on institutions that

this is a form of situational coercion. Gutheil and Appelbaum point out

that this would in effect not recognize the decisions made by large numbers of

people in institutions just because of the place they reside. They describe

more clearcut and explicit forms of coercion such as threatening the loss of

food or clothing if the patient does not follow recommended treatment. Competence

means that the patient has mental capacity to understand the information

presented and may a make a reasonable decision in order to give informed

consent. Psychiatric disorders can

affect all three elements of informed consent.

The philosophical look at coercion is a bit more complex

and it is selectively applied to the case of psychiatric care. Just looking at

the demographics raises some questions.

There are 1.3 million people in the US under guardianship or

conservatorship. At the same time there are 6.96 million people with dementia,

500,000 people with moderate to severe intellectual impairment, 36.25 million

with subjective cognitive impairment, and an undetermined number of people with

cognitive impairment and impaired capacity secondary to severe psychiatric

disorders. Those numbers suggest that there are not nearly enough guardianships

in place to provide substituted consent for people during medical

emergencies. In many jurisdictions

guardianships and conservatorships have to be pursued by family and that often

creates an undue financial burden. In the jurisdictions that actively ignore

conservatorships and guardianships – persons needing them often incur

unnecessary medical risk because treating physicians realize that they cannot

accept their consent to procedures involving risk – like surgeries.

Schramme has analyzed the issue of coercion in the following

ways. He breaks coercion down to threats and offers. For the purpose of his discussion, he states

that he is exclusively focused on autonomous choices that are contrary to

the will of the patient. These

choices cannot be made under the influence of threats but he outlines 3

scenarios where informed consent is lacking:

1. A patient is not

able to give informed consent – I think he makes a critical mistake here by

stating that most psychiatric patients are able to give consent and their

capacity is not globally impaired. It

clearly depends on illness severity and the stage of treatment. Most forensic

hospitals are charged with the task of restoring competency to mentally ill

offenders so that they can proceed to trial.

2. A patient

disagrees with treatment and makes that known but he is forced to accept

treatment anyway. The example given is a patient who if forced to take

medication because he is potentially dangerous to others. Schramme depicts this

as “a conflict between the patient’s will and the opinion of the doctor”. But where does the dangerousness come in? Why

is the patient unable to see that he is at risk from an extremely adverse

outcome (aggression and long-term incarceration or injury and possible death

due to a confrontation with the police) and not incorporate that into his

refusal?

3. A patient passively complies with a treatment

recommendation and does not make an overt decision. Schramme states that

although this would not typically be considered as coercive treatment – it all

depends on whether the consent is given freely or not. The implication is that

passive consent is not necessarily informed consent. Schramme invents the term “interactive

coercion” to suggest that psychiatric patients can be coerced by the

interpersonal relationship beyond what is typical of medical paternalism. That

presupposes that either nonpsychiatric physicians do not have relationships

with their patients, psychiatrists are masters at manipulating people, or some

combination.

From that point he goes on to provide 3 examples of interactive

coercion

Case 1: The psychiatrist

predicts that “damage or harm” will occur if the patient does not follow

certain course of action. This may or may not be coercion. Schramme gives the

example of taking away the patient’s cigarettes or writing them a suboptimal

report (the damage or harm) unless they comply with the prescribed course of

action. He acknowledges that harm can be

predicted due to non-compliance and it may not be a threat but a natural

consequence of untreated illness. Prediction of future causal events is a

warning and not a threat hence no coercion (p. 360). On the other hand, he suggests an “unusual” prediction

such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) if the patient had no previous

experience either it would constitute a threat.

The two necessary features for predicted harm to be a threat/coercion

would be that it needs to be intentional and unusual.

Case 2: The psychiatrist proposes a “detrimental unusual

consequence if the patient does not comply an example of effective threats as

coercion. In this case, if the threats are ineffective, they are

inconsequential, lead to no coerced decision. Schramme points out that “there

is no rigid line between a threat and a warning”. He gives an example of a

patient interpreting an action as a threat that may have had more to do with

the social roles of patients and nurses on the ward.

Case 3: The psychiatrist offers a beneficial unusual

consequence if the patient complies with a specific task. In this case there may

be intermediate conditionals. For example, the patient may not be motivated or

feel like socializing but forces themselves to do it anyway to get the offer.

Schramme introduces the idea of irresistible threats

and offers at this point. An offer becomes irresistible when there is no

other real alternative. In this case

even if the choice is voluntary, it can still be against one’s will. The best example is substance use disorders

where the person may not want to take the drug but acts on the drug as an

irresistible offer rather than a preferred motivation to remain abstinent. This

is an example of an offer that is irresistible and therefore coercive in that

it they are against the will of the person.

This is not a hard rule and Schramme emphasizes that all offers are not

bad and they depend on the subjective preferences of the patient. He goes on to develop the idea that “manipulation

and coercion – at least in psychiatric hospitals – do not only stem from predicted

consequences which bring people to do A, namely that they to prevent bad things

from happening.” (p. 367). Instead, he defines it as “an influence on the

autonomous will of the patient and not on the welfare of a person”. He closes by pointing out that institutional

and interpersonal dependencies can also result in irresistible offers to

psychiatric patients. He cites some examples

that today are irrelevant or exaggerated. For example – giving a patient

cigarettes if they take a medication or the offer of a “good report” for group

attendance. I have not observed either

of these happening on inpatient units over the course of my career even when

smoking was allowed on inpatient units. Even so, Schramme concludes that these coercive

offers are not necessarily morally wrong because “it might be good to

sacrifice the freedom of the patient for the sake of his well-being.” (p.

368). That is more than a trivial

distinction and I would argue is the basis of both civil commitment and

guardianship or conservatorship.

Szmukler and Appelbaum (4)

reviewed the coercion literature to date and described their own approach to

the issue of coercion. Their first step was noting that coercion was a loaded

term and describing a graduated systems of treatment pressures including:

(1) persuasion

(2) interpersonal leverage

(3) inducements

(4) threats

(5) compulsory treatment (in the community or as an

inpatient).

They provide an example of a community psychiatric nurse following

a patient in the community and how each of these pressures may work. They

develop models based on paternalism and capacity/best interests. Their definition of paternalism based on

previous research is given as:

“…a person is acting paternalistically towards another if

his action benefits the other; his action involves violating a moral rule with

regard to the other; his action does not have the other's past, present, or

immediately forthcoming consent, and the person believes he or she can make his

or her own decision on the matter. A paternalistic act requires justification

because it involves the violation of a moral rule but with the intention of

preventing a harm to the person.” (p. 240)

A series of questions is provided to answer whether or not

a paternalistic intervention is indicted. Answering those questions for a typical

emergency admission to an inpatient setting is typically balancing the deprivation

of personal liberty against death and disability. More subtle tradeoffs don’t end up as

admissions to inpatient units.

A capacity/best interest analysis is just the way it

sounds. The patient has impaired

decision making and is not able to make decisions in their best interest. Best

interest has a degree of subjectivity but the authors describe some general guidelines

based on previous work. The authors suggest that clinicians need a consistent

ethical framework for approaching these problems that is as rigorous as the

typical technical frameworks they use in practice.

“Protection of others” is described as a more difficult

problem for Szmukler and Appelbaum largely because of the subjectivity

involved. They discuss for example the low percentages of patients with mental

illness who are aggressive and the impossibility of prediction. They do not

mention that a number of features (acute care settings, acute threats, history

of violence/aggression, psychosis, pooling of cases, access to weapons) may greatly

increase risk but they are writing from the perspective of community rather

than inpatient care. They make an interesting comment: “Mental health professionals

may accept an obligation to notify appropriate authorities if there is a

serious risk of harm to others, but what is serious and who should instigate or

implement coercive responses is a matter for debate.” (p. 242). My understanding is that there is a

duty to warn in every state and the clinician not only needs to make a good

faith effort to contact the potential victim and take what other steps may be

necessary (eg. calling the police) to protect that person.

With that review, what assures that the term coercion is

not just another term used to inappropriately criticize monolithic

psychiatry? The standard dictionary

definitions implying malignant intent is certainly consistent with

inappropriate criticism. Schramme acknowledges

that there are situations where informed consent cannot occur due to a lack of

capacity but goes on to elaborate on treatment refusal where there is probably

lack of capacity and consent where the patient interactively coerced by

institutional or interpersonal scenarios. There is a high degree of subjectivity

involved in the interactive coercion scenarios.

Schramme seems to approach the problem hypothetically rather than

interactively. For example, as a clinical psychiatrist why would I ask if the

patient was perceiving a warning or a threat – I would just ask

them. In many cases agitated and paranoid patients are spontaneously accusing

staff of threats and malignant intent before any assessment or conversation has

occurred.

The best way I can think of how to proceed is to post a vignette – in the standard way that they are posted these days – a composite of features noted over the course of 25 years and not any specific patient:

Case Vignette

He is seen the next day by the C-L team. He has

some mild cognitive impairment and memory problems. He is detached and not saying much about why

he was hospitalized. His affect is restricted but he does not appear to be

depressed. He is requesting discharge but has no clear plan of what he will do

when he leaves. When asked about the

diabetes mellitus diagnosis he replies: “I can’t have it because I don’t have a

pancreas.” The C-L team recommends

referral to inpatient psychiatry and proceeding with a probate court

referral. The team speaks to a family

member there who talks at length about the family’s concern for the patient’s

safety and their relief that he is hospitalized. Is this coercion?

This is a realistic description of how patients are

admitted to acute care hospitals. The police officers in this case call EMS and

the patient is assessed by paramedics. The patient is taken to a local

emergency department where he is seen by a physician and a social worker and

admitted. In this case an involuntary hold is initiated by the police or by the

ED physician. A psychiatric diagnosis per se is not required since the

statutory definitions of mental illness are based on impaired judgement that

endanger the person or their health. Independently 6 people (none of whom were psychiatrists) agreed those conditions

existed.

He is seen and treated by surgery staff. He passively goes

along with treatment but there are obvious concerns about his capacity. Is this

a case of “interactive coercion” by surgical staff per Schramme’s formulation?

He is non-disclosing with psychiatry staff but the key observation is that he

no longer believes he has diabetes because he no longer has a pancreas. This is not a basis for adequate medical

decision making or self-care and that is further documented by his 4 episodes

of diabetic ketoacidosis, continued inability to manage this condition and the

question of cognitive impairment after episodes of coma. This patient is

referred for civil commitment and will be seen by pre-petition screeners

(typically one screener but a team of 4-5 people make the decision), a defense

attorney, 2 court appointed examiners, and a probate court judge. A total of about 9 people are involved in a

process to determine if the patient meets statutory requirements for civil

commitment and whether treatment should be court ordered.

Looking at the formulations of both Schramme and Szmukler

and Appelbaum is instructive. The

probate court proceeding that I describe is clearly a safeguarded capacity/best

interest scenario. The patient clearly lacks the capacity to make an informed

decision and consent on the basis that he no longer recognizes that he has

diabetes or that it needs to be treated despite life threatening consequences.

It is very clear that he would not get adequate treatment of diabetes or the

frostbite injuries if he was not hospitalized, observed, and actively treated.

By their formulation they would say that maximum treatment pressure is exerted

by compulsory treatment. In the final analysis, the ethical issue is that the

patient is being deprived of his right to continue to wander the streets without

adequate clothing or medical treatment for the compulsory treatment. Apart from a magical immediate restoration of

capacity is there a better short-term solution that is better designed to

protect his rights? I don’t see any.

An additional consideration is the issue of agency on

the part of the inpatient psychiatrist.

That psychiatrist has a fiduciary responsibility to the patient. That

involves discussing all relevant aspects of diagnosis and treatment with the

patient, including the concerns about his ability to care for himself. Is that

psychiatrist and agent of the state or as some philosophers like to put it –

the will of the state is being enacted though that psychiatrist? Definitely not

and here is why – the will of the state is transacted through the commitment

court and all of those personnel. The treating psychiatrist is unnecessary for the commitment proceeding and the court is focused on what their examiners conclude. Psychiatrists have no personal stake in whether somebody is detained in

a hospital by a court order. In fact, without a court order it is an unlawful

detention subject to both criminal and civil penalties. Over the years I have had to discharge many

people because the court did not produce a timely court order or decided to release

the patient. Further, in the actual

hearing the opinions of the court examiners are the ones the judges depend on.

The only interest of the inpatient psychiatrist is making an accurate assessment,

making sure all of the patient’s medical problems are treated, and making the

optimal recommendations for medical and psychiatric care. The inpatient

psychiatrist is also talking with the patient on a daily basis assessing

progress and attempting to establish a good working relationship with the

patient whether or not a court hold is in place or not. That working relationship

is possible when the patient recognizes that there is no adversarial relationship

with the inpatient psychiatrist. In fact, the treatment of patients on court

holds should be indistinguishable from voluntary patients.

By Schramme’s formulation that patient is not a competent

consenter. As noted about his passive cooperation with the burn surgeons,

endocrinology, and the inpatient psychiatrist might be construed as interactive

coercion. There is also a chance that it might not be according to these

definitions because the psychiatrist is discussing adverse outcome with the

patient but the discussion is based on what has happened many times already. Even with compromised cognitive capacity the

patient is able to acknowledge this and the fact that he does not want to end

up in a coma in the ICU gain. Another important aspect of these discussions is the

psychiatrist is very neutral and not reactive or blaming. They are a sincere

expression of concern given everything that is going on an what has happened to

the patient.

A final consideration here is that both philosophical and

legal approaches to involuntary treatment probably do not capture what is

really happening. For example the will or the autonomous will is the focus of

both the coercion and the involuntary treatment discussion. Reading though any paper on the will,

illustrates that it is a vague, changeable, and completely subjective concept. It is also not constant over time. When

philosophers like Schramme write about it – the are typically referring to an

individual and not a class of people. It makes more sense to talk about a

person’s conscious state rather than an isolated will. Conscious states are complex and

multidimensional (6). Even though they

cannot be accurately measured at this point – on a clinical basis it can easily

be observed that conscious states can change from being adept at self-care and

day to day living to states where inadequate self-care becomes self-endangering.

It makes very little sense to think that the will or autonomous will

of a person experiencing a major psychiatric illness is constant over time. The

goal of treatment ideally is to restore the autonomous will and assist the

patient with getting back to their baseline.

I have had that confirmed many times by people who benefitted from that

process.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

References:

1: Bureau of Labor

Statistics. Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2020 29-1223 Psychiatrists https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291223.htm

2: Schramme T. Coercive threats and offers in psychiatry.

In. Schramme T, Thome J (eds). Philosophy and Psychiatry. Walter de Gruyter;

New York; 2004: 357-369.

3: Gutheil TG,

Appelbaum PS. Clinical Handbook of

Psychiatry and the Law, 3rd edition. Lippincott, Williams, and

Wilkins, New York; 2000; p. 153-162.

4: Szmukler G, Appelbaum

PS. Treatment pressures, leverage, coercion, and compulsion in mental

health care, Journal of Mental Health. 2000 17:3, 233-244, DOI: 10.1080/09638230802052203

5: Walter J.

Consciousness as a multidimensional phenomenon: implications for the assessment

of disorders of consciousness. Neurosci Conscious. 2021 Dec 30;2021(2):niab047.

doi: 10.1093/nc/niab047. PMID: 34992792; PMCID: PMC8716840.

Supplementary 1: Workforce exposed to involuntary treatment scenarios:

There are an estimate 30,451 working psychiatrists in the

United States. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics 25,540 are

employed and the rest are self-employed.

Since it is very likely that acute care psychiatrists are employed by

hospitals 4,160 are in General Medical and Surgical Hospitals and 3,550 are in

Psychiatric and Substance Use Hospitals. There are currently 37,400 members in

the American Psychiatric Association and that number may reflect

researchers and the retired. The total pool of psychiatrists

who might be involved at some level in involuntary treatment is about 7,710

from the acute care setting but that is likely a gross overestimate for

several reasons. First, not all acute care settings treat people on an

involuntary basis. In any metro area emergency medical services (EMS) generally

brings the patients to only those hospitals who can provide the full array of

emergency services. Second, even among psychiatrists employed in hospitals only

a small percentage of them will provide direct care to patients who are there

on an involuntary basis. Third, there are very few free-standing psychiatric

hospitals or substance use facilities that accept anyone on an involuntary

basis. It is very likely that less than 10% of the psychiatric workforce ever

provides treatment to people on an involuntary basis.

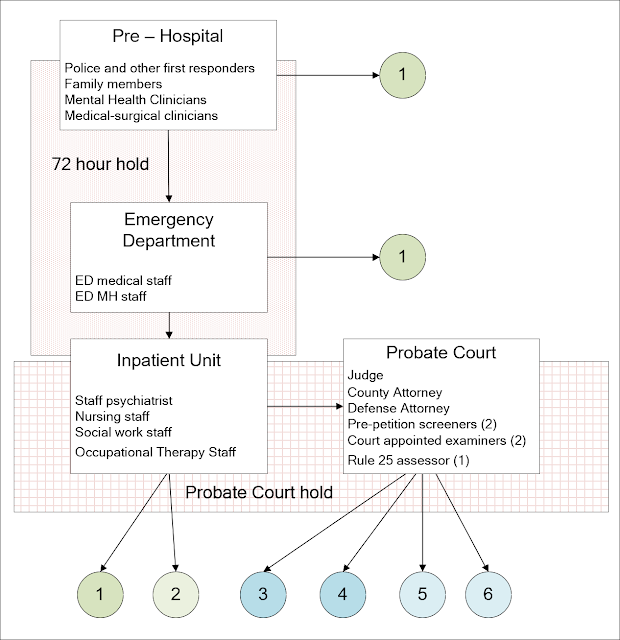

Supplementary 2: Graphic modification to show the emergency hold and probate court hold