There is a paper that just came out (1) that I consider a

must-read for all psychiatrists. Some

experts might qualify that and say that it is only necessary to know the

subjects if you are treating the medically ill, the elderly, pediatric

patients, patients with cardiovascular disease, or patients with cardiac risk

factors. The problem with those qualifications is that you have to know

everything in this paper (and others) in order to make that determination.

Beyond that you have to been trained in how to determine if your patient is

seriously ill or not. In the case of all medical specialists, serious illness generally

means treatment by another specialist or in a more intensive setting. For that

reason, the cardiac aspects of care in this paper are required knowledge.

Three of the authors of this paper are cardiologists, two

are psychiatrists, and one is a clinical pharmacist. They have produced a very

practical document on identifying problems with tachycardia, QTc prolongation,

sudden cardiac death, myocarditis, and dilated cardiomyopathy. They provide very specific endpoints and

suggest some basic intervention that can be done before the patient is referred

to cardiology. Examples would be assessment of tachycardia, suggested treatment

thresholds, common treatment interventions like beta-blockers and calcium

channel blockers, and referral to cardiology if there is a progression to other

cardiac symptoms, nonresponse to the initial therapy, or an arrhythmia beyond

sinus tachycardia. They provide similar guidance on the other common conditions

and relate them to second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs).

All of the authors are from the United Kingdom. I am not familiar with the standard settings

for practicing psychiatry in the UK, but in the US there is a high degree of

variability. For example, in practicing on inpatient settings it is not a

problem to order ECGs or even stat ECGs. Echocardiograms and other imaging

studies of the heart are easily obtained as well as cardiology consultation. In

a previous inpatient setting where I practiced, I requested a cardiology

consultation for a young woman with a QTc of 520 ms who required treatment with

antipsychotic medications. She was seen immediately and an electrophysiology study

was done. After that study I was advised by cardiology that I could safely

treat the patient with olanzapine. At the other end of the spectrum, I know

there are psychiatrists reading this who have no access ECGs, medical testing,

or cardiology consultants. They are often practicing in an office that lacks a

sphygmomanometer or staff routinely checking patient vital signs. Many of those

office settings are essentially nonmedical and any psychiatrist practicing there

- would need to bring in their own equipment and probably take their own vital signs. A basic standards would be that every practice setting for psychiatry in the country should have

the tools to make the measurements recommended in this paper, but I am not aware that any standard like that exists.

The second obstacle to realizing these guidelines is the way

electronic health records (EHR) are set up. Major organizations and the EHR

companies themselves produce templates that are typically designed for business

purposes rather than medical quality. A visit to a psychiatrist in that

organization results in that template being filled out with a business rather

than a clinical focus. In other words, sections of bullet points are completed

based on what coders believe will capture the necessary billing from insurance

companies. One of the key sections is often the review of systems (ROS). Because

these documents are not designed by physicians and there are no uniform

standards, a functional review systems is often not there. In the case of

cardiac symptoms, there needs to be a clear section that encompasses all the

symptoms described by the authors in this paper. As an example, take a look at

the cardiac symptomatology that I recorded in this post and the modified

extended review of systems that I typically ask patients about.

Any inpatient or outpatient assessment done by a psychiatrist should include a thorough medical history, a review of systems that is focused on medical rather than psychiatric systems, a set of vital signs including noting whether or not the cardiac rhythm or pulse is regular or irregular and a further description of the irregularity. A focal exam for additional heart and lung findings and determination of pulses and peripheral edema may be indicated. The take home point is that this history taking combined with a few additional findings should be all that is necessary to order further tests like an ECG, refer for an acute assessment, or refer to a primary care physician or cardiologist for further assessment. If the patient is being followed for the metabolic complications of SGAs, there may already be a fasting blood glucose, and lipid profile in the chart to assess additional risk factors. Over the years I have also found that recording a theory about why I think the patient is symptomatic is also very useful. In my practice that has ranged from medication side effects to an acute myocardial infarction.

With those issues we can proceed to consider the assessments

and treatments recommended by this group. I am not going to repeat the content

of the paper here. I recommend that any

interested psychiatrist or psychiatric resident get a copy of this paper and

study it in detail if you are not already familiar with the concepts. I will

list a few of the points that I found to be interesting after doing these

assessments for a long time.

Tacycardia is a

common problem in psychiatric patients and the population in general. Here the

authors were focused on tachycardia as a side effect of SGAs and haloperidol. They produced a table showing the incidence of

tachycardia across a number of SGAs and haloperidol and illustrate that

clozapine by far has the highest prevalence of tachycardia. In the table

haloperidol, asenapine, and sertindole at the lowest incidence of tachycardia

at about 1%. They point out this problem is generally self-limited but it

suggests a number of investigations that should be considered before monitoring

for improvement over time. The recommended treatments (bisoprolol, ivabradine) are

not recognizable medications for physicians in the US. In the US, beta-blockers

are commonly used. They suggested treatment is predicated on whether patients

are symptomatic or not with palpitations. Although UpToDate describes sinus tachycardia

as a benign condition with no worse outcome than a control group, this

tachycardia is drug-induced. My main concern with persistent drug-induced

tachycardia is tachycardia induced cardiomyopathy. My other concern is that

common causes of tachycardia in the patients I see include excessive use of

caffeine (alcohol, or other substances), deconditioning, and sleep deprivation.

Establishing a baseline prior to any of these prescriptions is important. There is always a lot of debate about whether

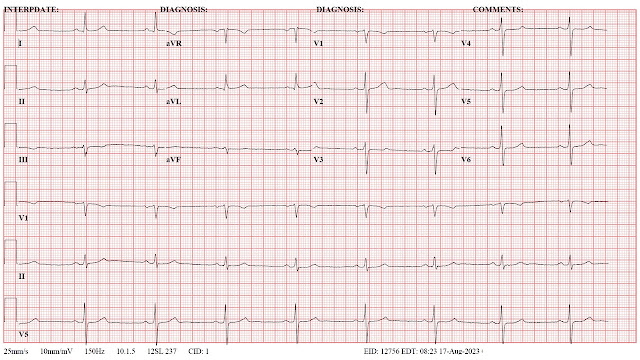

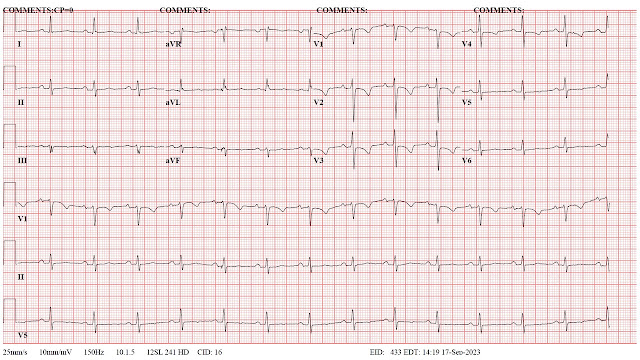

or not electrocardiogram should be done. I agree with the authors that the ECG

is an inexpensive screen and should be done to make sure that it is a sinus

rhythm. Another bit of information that may not be available is whether the

pulse is irregular or not. Many clinics have automatic blood pressure and heart

rate measuring devices and not all of them make that determination.

The section on the QTc interval was interesting because the

authors provide very clear guidance on measuring QTc, the problems with that

measurement, and very clear guidelines on what to do about that measurement.

They cite the threshold for stopping or reducing treatment with QTc prolonging

agents as an interval greater than 500 ms or relative increase of greater than

60 ms. They also use the American Heart Association definitions of prolonged as QTc > 450 ms in men and > 460 ms in women. They point out that the most common

calculation of QTc (Bazett’s formula) overcorrects heart rates greater

than 100 BPM and they suggest that other formulae may be used for that situation. Like

many psychiatrists I have ordered hundreds of ECGs for determining baseline

cardiac conduction. The vast majority have been normal. The ones that were not - were typically unrelated to the medication I was prescribing. Many conduction

abnormalities were related to increasing age and latent cardiac problems. The

other common scenario where I am concerned about cardiac conduction is

polypharmacy. It is possible for a person to be taking multiple medications for

psychiatric indications - all of which may affect cardiac conduction. The drug

interaction software for most EHRs as a very low threshold for this type of

interaction.

The myocarditis section of this paper was very interesting.

In Table 1 - the authors included prevalence figures for myocarditis in the

same table where they documented the prevalence of tachycardia for each

medication. The figures are based on isolated case reports. The review the

controversy about clozapine and widely variable reports of incidence. The

incidence quoted for Canada and the USA was 0.03%. Different criteria used to

diagnose myocarditis was considered an important point of variance. A set of

clinical criteria is provided in the paper as well as when to refer to a

cardiologist. In addition to the ECG, serum troponin, C-reactive protein,

echocardiogram, and cardiac MRI are considered. The referral indicators

included elevated troponin, CRP, and abnormalities at echocardiogram. My

interpretation is that psychiatrists in the US who have access to those

measures and ready access to cardiologists could potentially use those markers.

The most reasonable approache is to be able to recognize the symptoms of

myocarditis clinically and be able to refer the patient to cardiology were most

of the testing could occur. The clinical description of myocarditis in the paper

sounded very similar to typical viral myocarditis with chest pain, dyspnea, flu-like

illness, fever, and fatigue. These are nonspecific symptoms especially during

influenza season. The clinician has to have a high index of suspicion based

on treatment with clozapine. The paper contains an ECG tracing of saddle

-shaped ST elevation considered to be a finding consistent with myocarditis. It

was visible in most leads.

The approach to dilated cardiomyopathy was very similar in

terms of recognizing the symptoms of congestive heart failure and the necessary

investigations. There was guidance and when to request an echocardiogram based

on BNP and in NT-ProBNP measures as well as when referral to cardiology was

indicated. The standard of care in the US is the psychiatrist recognizing what is

happening but not treating dilated

cardiomyopathy. In most clinical with limited resources, this is a good reason to have a referral relationship with a primary care clinic - especially one that can do the testing on site. There are many primary care and even urgent care clinics that cannot do the testing suggested in this paper.

In the case of myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy, the

question of whether a patient should be re-challenged if they need the offending

medication and their underlying cardiac condition has improved. The authors

suggest close consultation with a cardiologist at that point. Given the data my

own practice has been to not re-challenge with the offending medication but to

try a different treatment modality. The concern in the article is that the

patient’s ability to function from a psychiatric standpoint may require use of

that specific medication. I do not think that enough is known about the outcome

of either condition to resume the original medication, but if favorable

outcome studies or case reports exist, I might revise that opinion.

All things considered this is an outstanding article on the

cardiotoxicity of SGAs. The graphics in the paper also excellent with

management flow diagrams and well-designed tables. The authors restate that cardiotoxicity is

very low. It is the job of every

psychiatrist who prescribes these medications and others to make sure that

patients are monitored for these complications. There is always a question of

what constitutes adequate informed consent when we are talking about a

potential complication rate of 0.03%. At that level it is certainly possible

that many psychiatrists have never seen these complications and never will. I

think it is reasonable to let people know that medications they are taking can

cause rare but potentially serious side effects including death. The informed

consent issue was not touched on in the paper but a day-to-day practice it is

an important one. From a practical standpoint I generally advise people that if they are taking a medication with rare but potentially life threatening side effects, they have to take all physical symptoms seriously. Physical symptoms cannot be attributed to common explanations like colds, the flu, or gastroenteritis.

This paper had a very specific focus and it did not touch on the other metabolic and neurological complications of these medications that require additional screening. One of the reasons I posted my ROS document on this blog was to make ti easy for any clinic or psychiatrist to build their own template with the relevant questions needed for their own patient population.

For some psychiatrists and clinics the work in cardiac screening just got a lot harder. For others who have been doing all of this for decades - there will be very little difference.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

References:

1: Sweeney M, Whisky

E, Patel RK, Tracy DK, Shergill SS, Plymen CM.

understanding and managing cardiac side effects of second-generation

antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Br J Psych Advances 2019:

1-15.

2: Patel RK, Moore AM, Piper S, Sweeney M,

Whiskey E, Cole G, Shergill SS, Plymen CM. Clozapine and cardiotoxicity - A

guide for psychiatrists written by cardiologists. Psychiatry Res. 2019 Jul

24:112491. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112491.

[Epub ahead of print] Review. PubMed PMID: 31351758.