On August 30, 2023, I finally bit the bullet and had a cardiac ablation for atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter. If you are one of those rare readers of this blog you may recall me writing about it and how it occurred in the first place. I happened to be speedskating 19 years ago on the John Rose Oval and just completed my warm up laps. I looked at my heart rate monitor and my pulse was 170 BPM. I pulled up to stretch a little and suddenly my HRM was chirping irregularly and the rate was 240 BPM. I checked my carotid pulse and knew I was in atrial fibrillation. I drove down to the hospital where I was cardioverted with flecainide and metoprolol and have been taking those medications ever since.

In the interim, I have seen a sports cardiologist several

times, 5 electrophysiologists (EP), and two general cardiologists as well as my

primary care physician and the physicians that cross cover for him. I have also

been seen in the emergency department for a heart rate that was down to 25

beats per minute and atrial bigeminy. The physician in the ED thought that I

might need a pacemaker, but it turns out that the combination of flecainide and

metoprolol can cause significant bradycardia. Once I learned that I started

cutting 25 mg tablets into quarters (6.25 mg) and would typically take two of

those tablets per day. I also learned that if you take flecainide, you also

need to take a beta blocker or a calcium channel blocker to prevent atrial

flutter. Atrial flutter is difficult to

diagnose without an ECG because clinically it can seem like sinus

tachycardia. For example, I have had the

flu or taken corticosteroids for asthma and developed tachycardia. When I started running rates of 130 bpm, that

seemed a little high for sinus tachycardia.

I decided to get an ECG and it was atrial flutter. I had to figure all

of that out, because my initial plan was to taper off metoprolol and that is

unrealistic.

At the same time, the combination at times would cause

severe bradycardia. I had a nocturnal

heart rate of 35 BPM recorded on a Holter monitor and saw a cardiologist. We agreed to stay at metoprolol 6.25 mg BID

unless there were extraordinary circumstances.

That generally works but my heart rate can still get into the 40s range.

That led me to the stage to consider the ablation. The other factor is that the second EP

cardiologist that I saw 15 years ago told me to wait on an ablation because the

technology was not good enough. When I saw him this Spring – he thought it had

matured and recommended the procedure. He also told me that both the atrial

fibrillation and atrial futter could be ablated in a single session rather than

two and that was the first time I heard that.

For about 15 years I have been titrating what most people

consider to be microdoses of metoprolol (Physicians typically say: “I have never heard of a dose that

small.”) against the flecainide and it has been holding very well. I get about

1 major episode of afib per year that may last 2-3 hours. I typically take the next dose of flecainide

and 12.5 of metoprolol instead of 6.25.

Multiple 24 hr Holter monitors and clinical assessments by cardiologists

have not resulted in a better combination.

They were adamant about not increasing the flecainide because of the

risk of QRS prolongation and ventricular arrythmias. There was a consensus to try the ablation –

even if the pandemic had persisted.

Researching the procedure followed three lines of

evidence. The first was efficacy and

that seems to be a moving target. Conventional wisdom for a long time was that

rate control (maintaining a heart rate of < 100 bpm even if you were in

atrial fibrillation) and rhythm control (maintaining normal sinus rhythm)

produced equivalent results. It turns out that is true only if hemodynamic

stability is maintained and for some people it is not. When that happens, they develop significant

symptoms like shortness of breath, lightheadedness, dizziness, chest pain, and

can even develop congestive heart failure and renal failure. When all of that

is not planned it is riskier to stabilize the person. There is also concern

that rate control leads to quality-of-life (QoL) problems associated with both

the direct symptoms and indirect symptoms like anxiety about palpitations and

the arrhythmia. There seems to be movement in the direction of an attempt to

stabilize the rhythm with medication and if that fails try the ablation. There

is a QoL

rating scale available for atrial fibrillation. In terms of likelihood of ablating the

arrhythmia the frequent quotes are generally 2/3 to ½ of patients, but the data

is complicated by the number and intensity of cardiac morbidities.

The second line of evidence was complications and serious

complications were noted. Radiofrequency

ablation of arrhythmias in some cases produces a full thickness burn to the

heart muscle. As a result, it can damage

adjacent structures including the esophagus and the phrenic nerve. It can also lead to pericardial effusions and

cardiac tamponade. In a very worst-case scenario atrial-esophageal fistula with

gas in the left atrium and left ventricle essentially causing an air lock in

the pumping mechanism of the heart (4).

The third line was something I had not considered in the

past and that is that atrial fibrillation is progressive. In other

words, even if you have good rhythm control with medication, unless something

is done to alter the electrical substrate the likelihood of maintaining a

normal sinus rhythm after an ablation decreases over time. Accumulating cardiac

problems outside of atrial fibrillation can predispose to the condition and

make it harder to treat.

Some additional intangibles were considered. I would like

to get back on the ice speedskating. That will take rhythm control and some

resilience against exercise induced tachycardia. Rhythm control is important because atrial

fibrillation reduces typical cardiac output by 20-30% based on inadequate

filling and pumping cycles due to the irregular heartbeat. Augmentation of ventricular filling is also

adversely affected due to a lack of coordinated atrial contractions. I am hoping the ablation gets me close to

that goal. There are some theories that interoceptive

signaling in the form of accelerated heart rate from any cause can lead to

anxiety. Certainly many people with

arrhythmias have anxiety that may seem explainable on a general medical concern

basis but there may also be an autonomic component as well as a cognitive

component based on the multiple concerns of treating a chronic disorder than

can cause stroke and congestive heart failure.

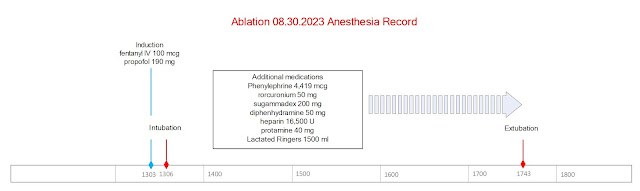

What has happened so far? I underwent the procedure. It was 4 hours and 40 minutes in duration from

intubation to extubation. The general anesthesia given is shown in the graphics below. The top graphic is the one I made until the official graphical anesthesia record could be located as the second graphic. To do the ablation 4 catheters were placed in the right femoral vein and

one in the left. I don’t know the technical details of those catheters only

that one is for cryoabalation/isolation of the pulmonary veins in the left atrium, one is for mapping the electrical fields in the surrounding tissue, and one is

for a radiofrequency ablation of the a CTI line (cavotricuspid isthmus) in the

the right atrium. That procedure targets

atrial flutter. The plan was do the CTI line ablation first and then puncture

the interatrial septum and then enter the left atrium with the cryoablation

catheter for the pulmonary vein isolation. The technical details are more complex since the ablation sites and surrounding areas need to be checked to makes sure that the abnormal conduction sites have been eliminated and no new pathways are evident. The phrenic nerve and esophagus are also checked to make sure there is no damage from ablation that occurs in proximity to these structures.

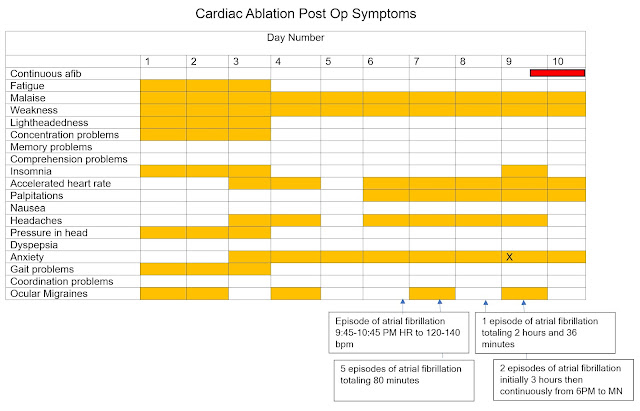

I tried to capture the post-procedure course by in the following

graphics. In clinical practice it was

common for me to see people of all ages who had ablations for various

arrhythmias. In some cases, they were told to “go home and throw your

medications away!” as a result of the ablation. That may apply to some arrhythmias but not

atrial fibrillation. They told me to expect no changes in the medications for 3

months and that I would be taking the same doses of metoprolol and flecainide. Later at the time of discharge – they told me

that in some cases there is a very rocky course until things heal up from the

procedure and that it was not uncommon for people to get palpitations and even

a return of the rhythm problems.

As noted in the graphics – the course to date has been

rocky. At this point much more atrial

fibrillation than I have experienced in the past 16 years and much longer

duration. In my reading about why athletes

get atrial fibrillation and the associated experiment work in that area –

running sustained high heart rates causes remodeling of the biological substrate

of the heart and that makes continued atrial fibrillation more likely. In 16

years, I rarely had an episode that lasted longer than 2 hours and lately more

seem to end in less than an hour. As I type this today, I have been in atrial fibrillation

for going on 48 hours continuously and just this morning converted to a rapid ventricular

response meaning that my ventricular rate is the same as the atrial rate of 150

bpm. Estimated maximum heart rate for exercise at my age is about 130 bpm.

A critical question for anyone contemplating an ablation

procedure on a non-acute basis like I did is the post operative course. I was

very aware of the low frequency serious and lethal complications, but not the

specific about length of time to recovery and what the symptoms might be. Most people experience significant if not

disabling symptoms for months rather than days or weeks following the

procedure. That is based on a small study where they did detailed interviews on

what happened to the subjects following the ablation (11). It is available to read online and I would

encourage anyone interested in the procedure or knowing more about the

procedure to read it. One of the authors' conclusions is

“The majority (85%) of the study sample did improve at six

months, but the process was much slower and more difficult than expected.

Although the symptom burden post-ablation did decrease over the six months,

only 50% of subjects (n=10) were symptom-free and off anti-arrhythmic

medications at six months.” (reference

11) These findings are qualified by the study sample size as well as the possibility of selection bias since the researchers were looking for people who could tolerate the protocol of completing rating scales and lengthy interviews about potential adverse events. Reference 11 is also very useful in terms for what kind of recovery time to expect - especially in terms of fatigue and more frequent contact with the healthcare system after atrial fibrillation ablation (12).

That is certainly consistent with my experience. Right at

this moment I have been in atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter continuously

for 48 hours. My heart rate is 160 bpm

at rest. I am contemplating taking more

medication on my own initiative or going to the ED for cardioversion. I am scheduled for a cardioversion in the cardiology clinic on Wednesday September 13 - but I don't know if I can hold off that long. I guess I am hoping for a break. There are

many mitigating factors. Whatever happens tonight – I hope to add more to this

post soon. This is an important topic

that has been neglected for too long.

Final qualifier on this post to point out that this is my experience and it does not mean it would be your experience. Much of the sensationalism about medicine in the media is based on oversimplified dichotomous thinking. Medications, procedures, tests, doctors and even diagnoses are seen as all bad or all good. Human biology is very complex and there are few if any medical interventions that address that level of complexity. That typically means that over any population there will be an array of outcomes and most of them will not be explainable. That is a hard pill to swallow but that is the state of the art of modern medicine.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

References:

1: Alobaida M,

Alrumayh A. Rate control strategies for atrial fibrillation. Ann Med. 2021

Dec;53(1):682-692. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2021.1930137. PMID: 34032538; PMCID:

PMC8158272.

2: Barbero U, Ho SY.

Anatomy of the atria : A road map to the left atrial appendage.

Herzschrittmacherther Elektrophysiol. 2017 Dec;28(4):347-354. doi:

10.1007/s00399-017-0535-x. Epub 2017 Nov 3. PMID: 29101544; PMCID: PMC5705746.

3: Lim HS, Schultz

C, Dang J, Alasady M, Lau DH, Brooks AG, Wong CX, Roberts-Thomson KC, Young GD,

Worthley MI, Sanders P, Willoughby SR. Time course of inflammation, myocardial

injury, and prothrombotic response after radiofrequency catheter ablation for atrial

fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014 Feb;7(1):83-9. doi:

10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000876. Epub 2014 Jan 20. PMID: 24446024.

4: Thomson M, El

Sakr F. Gas in the Left Atrium and Ventricle. N Engl J Med. 2017 Feb

16;376(7):683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm1604787. PMID: 28199804.

5: Manolis AS.

Transseptal Access to the Left Atrium: Tips and Tricks to Keep it Safe Derived

from Single Operator Experience and Review of the Literature. Curr Cardiol Rev.

2017;13(4):305-318. doi: 10.2174/1573403X13666170927122036. PMID: 28969539;

PMCID: PMC5730964.

6: Singh SM, Douglas

PS, Reddy VY. The incidence and long-term clinical outcome of iatrogenic atrial

septal defects secondary to transseptal catheterization with a 12F transseptal

sheath. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011 Apr;4(2):166-71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.959015.

Epub 2011 Jan 19. PMID: 21248245.

7: Kato Y, Hayashi

T, Kato R, Takao M. Migraine-like Headache after Transseptal Puncture for

Catheter Ablation: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Intern Med. 2019

Aug 15;58(16):2393-2395. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.2519-18. Epub 2019 Apr

17. PMID: 30996181; PMCID: PMC6746642.

8: Hoshina Y, Iijima

H, Kubota M, Murakami T, Nagai A. Case of atrial septal defect closure

relieving refractory migraine. Clin Case Rep. 2022 Nov 6;10(11):e6484. doi:

10.1002/ccr3.6484. PMID: 36381060; PMCID: PMC9637252.

9: Azarbal B, Tobis

J, Suh W, Chan V, Dao C, Gaster R. Association of interatrial shunts and

migraine headaches: impact of transcatheter closure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005

Feb 15;45(4):489-92. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.075. PMID: 15708691.

10: Schwedt TJ. The

migraine association with cardiac anomalies, cardiovascular disease, and

stroke. Neurol Clin. 2009 May;27(2):513-23. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2008.11.006.

PMID: 19289229; PMCID: PMC2696390.

11: Wood KA, Barnes

AH, Paul S, Hines KA, Jackson KP. Symptom challenges after atrial fibrillation

ablation. Heart Lung. 2017 Nov-Dec;46(6):425-431. doi:

10.1016/j.hrtlng.2017.08.007. Epub 2017 Sep 18. PMID: 28923248; PMCID:

PMC5811184.

12: Wood KA, Barnes AH, Jennings BM. Trajectories of Recovery after Atrial Fibrillation Ablation. West J Nurs Res. 2022 Jul;44(7):653-661. doi: 10.1177/01939459211012087. Epub 2021 Apr 26. PMID: 33899608; PMCID: PMC8801207.

13: Björkenheim A, Brandes A, Magnuson A, Chemnitz A, Svedberg L, Edvardsson N, Poçi D. Assessment of atrial fibrillation–specific symptoms before and 2 years after atrial fibrillation ablation: do patients and physicians differ in their perception of symptom relief?. JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology. 2017 Oct;3(10):1168-76.

14: Dorian P, Angaran P. Symptoms and Quality of Life After Atrial Fibrillation Ablation: Two Different Concepts. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2017 Oct;3(10):1177-1179. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2017.06.007. Epub 2017 Sep 13. PMID: 29759502.

15: Steinbeck G, Sinner MF, Lutz M, Müller-Nurasyid M, Kääb S, Reinecke H. Incidence of complications related to catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter: a nationwide in-hospital analysis of administrative data for Germany in 2014. Eur Heart J. 2018 Dec 1;39(45):4020-4029. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy452. PMID: 30085086; PMCID: PMC6269631.

16: Levy S. Overview of catheter ablation of cardiac arrhythmias. In: UpToDate, Connor RF (Ed), Wolters Kluwer. (Accessed on January 17, 2023)