(click to enlarge)

This post is part of my apparent never-ending quest to get

complex illnesses and blog about them.

About 15 years ago, I saw my primary care physician and described some

dermatology problems that I was having.

I won’t get too deep into the weeds about my symptoms, but somewhere

along the line I also recalled that my father had similar symptoms. In those

days back in the 1950s and 1960s he really did not get any formal

diagnosis. He was told instead that the

somewhat matted lesions he had on his face should be “drained” and his

physician cut into them with a scalpel. Eventually

they cleared up on their own. In my case I was given some topical metronidazole

that seemed to work for local outbreaks and have been using it ever since. It

seems good for focal lesions but it does not seem to do much for more global

symptoms such as a burning and stinging sensation of the more recently

discovered ocular symptoms of rosacea.

I first started to diagnose it and refer it for treatment

when I was seeing patients in acute care psychiatric units. I acquired a text that was considered

state-of-the art in the late 20th century (1) to assist me in

describing rashes and diagnosing dermatology diseases. The definition of rosacea was: “Papules and

papulopustules occur in the center of the face against livid erythematous background

with telangiectasias. There is also quite often diffuse connective tissue and

sebaceous gland hyperplasia and sometimes hypertrophy of the nose (rhinophyma)”

(p. 730). The disease was described as

progressive stages rather than discrete phenotypes and the pathology of each

stage was described and as a chronic inflammatory condition.

Little was known about the pathophysiology at the time but

the usual suspects of genetic predisposition and relationships to diet and

other potential irritants. The mite Demodex folliculorum was suspected. Various irritants like sun, mechanical

irritation, heat, cold, hot drinks, alcohol, and caffeine increased the

erythema (redness). The authors

described progressive stages rather than distinct phenotypes. Eye involvement

was known at the time including complications like blepharitis, conjunctivitis,

iritis, and in some cases keratitis of the cornea leading to blindness. Associated symptoms were eye pain and

photophobia. The main treatment

described was systemic and topical antibiotics, sunscreen and avoiding other

irritants.

Today like many diseases there are clearer diagnostic

criteria and there is also accumulated knowledge on possible pathophysiology. The

American Rosacea Society proposed the criteria listed in the following

table. Currently 2 or more major features are diagnostic. The criteria are controversial because they

include a number of features with low predictive value. A subsequent update by the Global ROSacea

COnsensus Panel (ROSCO) modified the criteria and expanded to 6 phenotypes. Note

that there are no formal biomarkers for the phenotypes just very approximate

clinical descriptions.

|

Primary Features

|

Central distribution of:

Transient erythema

(flushing)

Permanent erythema

Papules/pustules

Telangiectasia

|

|

Secondary Features

|

Burning or stinging sensation

Ocular involvement

Edema

Dryness

Plaque formation

Peripheral location

Phymatous changes

|

|

Phenotypes

|

Subtypes:

Erythematotelangiectatic

Papulopustular

Phymatous

Ocular

Variant:

Granulomatous

|

|

ROSCO

Phenotypes

|

|

Flushing

|

|

Persistent Erythema

|

|

Telangiectasia

|

|

Papules/pustules

|

|

Phymatous changes

|

|

Ocular manifestations

|

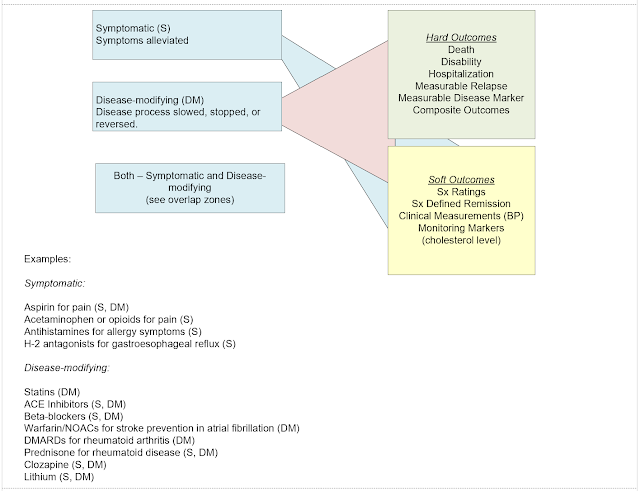

This post is not about how to make the diagnosis or treat

this disorder, although every physician including psychiatrists should be able

to recognize the condition. I am hoping to convey some diagnostic imperatives

and discuss disease complexity that underlies fairly basic diagnostic

categories. It will also be apparent that basic science research has added

quite a lot in terms of the treatment or this disorder, but that a lot of

uncertainty remains.

Let me start with pathophysiology. There is always plenty

of controversy about pathophysiology despite the fact that not much is known

about it – even in common complex diseases.

That includes psychiatric diseases and yet people seem to suspend their

critical thinking when it comes to psychiatry – and claim that the lack of

pathophysiological mechanisms and medications specific for that pathophysiology

represents something unique. In the case of rosacea since it is considered a

complex inflammatory disease there are a couple of approaches to looking at

pathophysiology. The first is to consider the two main types of immunity and

how they are modified. The first general

type in innate immunity basically comprised of various barriers to

pathogens like skin and mucous membranes, non-specific immune cells, and

inflammatory proteins like interferons.

Local chemical environments can also produce a number of physical and

chemical conditions that can kill potential pathogens. Adaptive immunity is more specific and

it depends on recognitions on antigens on pathogens and the resulting reactions

with antibodies and immune cells. In the case of rosacea there are different

theories involving both types of immunity.

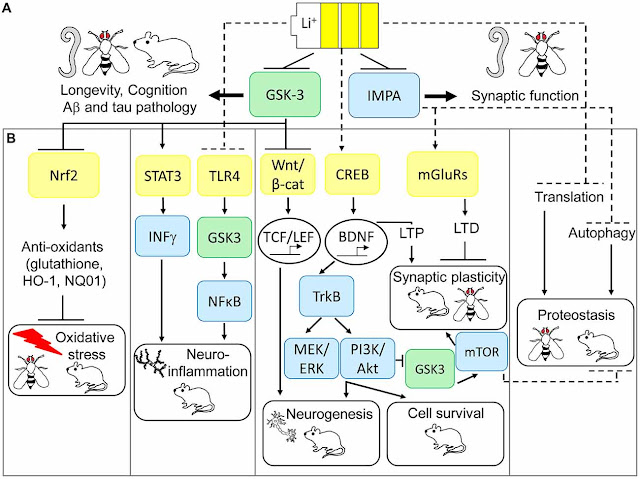

One theory suggests that there is increased production of

cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) – a component of innate immunity that

leads to the inflammatory process associated with rosacea. CAMP gene expression is regulated by VDR (a

Vitamin D dependent transcription factor) and C/EBPα (a

Vitamin D independent transcription factor). During winter months there is not

enough UV light to produce CAMP by the Vitamin D dependent process. This theory

suggests there is a mutation that allows for C/EBPα activation leading to

toll-like (TLR) receptor mediated immune responses and upregulation of

endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress responses.

Although this sequence of events leads to increased inflammation due to

a number of end products [sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), LL-37 the active

cleavage product of CAMP, interleukin-1β (IL-1β),

IL-17, IL-18, as well as associated T-helper (Th) cells and chemokines. This process is depicted in the graphic at

the top of this post (click on it to enlarge).

The activation of this inflammatory reaction can be verified by

measuring end products in both the epithelium and the ocular surface. Dry eye clinics have the capacity to check

for tear osmolarity and inflammatory markers like matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) – an enzyme. MMP-9

can be done as a point-of-care test so that the results are available within

minutes.

A logical question to ask is whether widespread activation

of the inflammatory response associated with rosacea can affect organ systems

other than skin. The degree of inflammation is also a factor. It is common to

see patients with diverse findings ranging from mild erythema on the cheeks to

intense erythema of the eyelids and central facial areas. The question of other

organ systems has been examined with interesting findings. Cardiac,

neurological, and psychiatric conditions are all more likely in patients with

rosacea (6-15). In terms of cardiac

conditions that includes a modest increased risk for atherosclerotic heart

disease. There is less evidence of

increased risk for arrhythmias but that increased risk has been demonstrated

for other inflammatory dermatological conditions like atopic dermatitis and

psoriasis (14). In the papers where the authors comment on possible

pathophysiology the suggested mechanisms are innate immunity, adaptive

immunity, or both.

Rosacea is a complex inflammatory disease that can lead to significant

ocular and dermatological complications. According to one theory the

pathophysiology of the illness may have been caused by an adaptive mutation in

Nordic populations that preserved innate immunity when Vitamin D dependent

factors were not available due to decreased photoperiod and UV light. The

general consensus is that there is no agreed up theory to explain the

underlying pathophysiology and like the immunological literature in psychiatry

different authors have differing hypotheses.

Psychiatrists need to be aware of the condition because

about 5% of the population has it, it is readily diagnosed based on visual

inspection but the ocular phenotype may require referral to a specialized dry

eye clinic. The dry eye disease untreated can lead to significant eye

complications. From a theoretical perspective there are direct parallels with

the psychiatric process including the categorial diagnoses, theoretical

pathophysiology, and a number of treatments that may or may not address that

pathophysiology. Current clinical and

future research questions include:

1: Are there immunological

mechanisms common to both rosacea and common psychiatric disorders? Immune etiopathophysiological hypotheses for

psychiatric disorders have been proposed since 1985 (16) and their complexity

and the number of disorders covered have only increased since that time. Over the same time frame much more has been

discovered about the basic science of immunology. Do the proposed immune

mechanisms of rosacea affect other organ systems in the same way that the skin

is affected? Are these mechanisms

responsible for some of the early observations about PET imaging of the brain

(15) in rosacea?

2: What about the

immunological products of rosacea? Is it

possible that they are contributing to what are considered symptoms of general

disorders like anxiety and depression?

Cytokines like IL-17 can lead to flu-like symptoms and a general feeling

of malaise – could this lead to the appearance of a treatment resistant anxiety

or depressive disorder? Could it lead to

the misdiagnosis of a psychiatric disorder?

3: Even if there is

no direct physiological connection between rosacea and anxiety and depression

can pathophysiological processes lead to psychiatric complications especially

with pre-existing anxiety and depression. For example- rosacea leads to neurovascular

hyperactivity in the form of facial flushing and skin sensitivity to a variety

of physical and chemical irritants. If you have a pre-existing concern about

embarrassment, humiliation, and obvious physical signs of anxiety rosacea

compounds that. It also can lead to

sleep problems due to skin sensitivity that will compound any associated

psychiatric disorder.

4: Dealing with the

stress of a chronic disorder activates additional processes that can either

exacerbate or precipitate anxiety or depression. There is an inherent bias to

see conditions like rosacea as a minor problem rather than a potentially very

stressful problem with considerable morbidity that can actually lead to

physical disability.

That is what I have found to be interesting about rosacea

and dealing with it at an individual level. I hope there is more research focused on it in

the future from the combined perspectives of psychiatry, dermatology, and

immunology. There is much more to be

learned.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

References:

1: Braun-Flaco O,

Plewig G. Wolff HH, Winkelmann RK.

Dermatology. Springer-Verlag,

Berlin 1991: 730-731.

2: Melnik BC. Rosacea: the blessing of the Celts – an

approach to pathogenesis through translational research. ACTA Derm Venerol 2016; 96: 147-156.

3: Ratajczak MZ, Pedziwiatr D, Cymer M,

Kucia M, Kucharska-Mazur J, Samochowiec J. Sterile inflammation of brain, due

to activation of innate immunity, as a culprit in psychiatric disorders.

Frontiers in psychiatry. 2018 Feb 28;9:60.

4: Salam AP, Borsini A, Zunszain PA. Trained

innate immunity: A salient factor in the pathogenesis of neuroimmune

psychiatric disorders. Molecular Psychiatry. 2018 Feb;23(2):170-6.

5: Zengeler KE, Lukens JR. Innate immunity at

the crossroads of healthy brain maturation and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Nature Reviews Immunology. 2021 Jul;21(7):454-68.

6: Garrett ME, Qin XJ, Mehta D, Dennis MF, Marx

CE, Grant GA, VA Mid-Atlantic MIRECC Workgroup, PTSD Initiative, Injury and

Traumatic Stress (INTRuST) Clinical Consortium, Psychiatric Genomics Consortium

PTSD Group, Stein MB. Gene expression analysis in three posttraumatic stress

disorder cohorts implicates inflammation and innate immunity pathways and uncovers

shared genetic risk with major depressive disorder. Frontiers in Neuroscience.

2021 Jul 29;15:678548.

7: Pape K, Tamouza R, Leboyer M, Zipp F.

Immunoneuropsychiatry—novel perspectives on brain disorders. Nature Reviews

Neurology. 2019 Jun;15(6):317-28.

8: Bekkering S, Domínguez-Andrés J, Joosten LA,

Riksen NP, Netea MG. Trained immunity: reprogramming innate immunity in health

and disease. Annual review of immunology. 2021 Apr 26;39:667-93.

9: Dounousi E, Duni A, Naka KK, Vartholomatos G,

Zoccali C. The innate immune system and cardiovascular disease in ESKD:

monocytes and natural killer cells. Current Vascular Pharmacology. 2021 Jan

1;19(1):63-76.

10: Scott Jr L, Li N, Dobrev D. Role of

inflammatory signaling in atrial fibrillation. International journal of

cardiology. 2019 Jul 15;287:195-200.

11: Zhou X, Dudley Jr SC. Evidence for

inflammation as a driver of atrial fibrillation. Frontiers in cardiovascular

medicine. 2020 Apr 29;7:62.

12: Bellocchi C, Carandina A, Montinaro B,

Targetti E, Furlan L, Rodrigues GD, Tobaldini E, Montano N. The Interplay

between Autonomic Nervous System and Inflammation across Systemic Autoimmune

Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022 Feb 23;23(5):2449.

13: Choi D, Choi S, Choi S, Park SM, Yoon HS.

Association of Rosacea With Cardiovascular Disease: A Retrospective Cohort

Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021 Oct 5;10(19):e020671. doi:

10.1161/JAHA.120.020671. Epub 2021 Sep 24. PMID: 34558290; PMCID: PMC8649155.

14: Schmidt SAJ,

Olsen M, Schmidt M, Vestergaard C, Langan SM, Deleuran MS, Riis JL. Atopic

dermatitis and risk of atrial fibrillation or flutter: A 35-year follow-up

study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Dec;83(6):1616-1624. doi:

10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.039. Epub 2019 Aug 20. PMID: 31442537; PMCID:

PMC7704103.

15: Liu Y, Xu Y, Guo

Z, Wang X, Xu Y, Tang L. Identifying the neural basis for rosacea using

positron emission tomography-computed tomography cerebral functional imaging

analysis: A cross-sectional study. Skin Res Technol. 2022 May 29. doi:

10.1111/srt.13171. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35644027.

16: Knight JG. Possible autoimmune mechanisms in

schizophrenia. Integrative Psychiatry

1985; 3: 134-143.