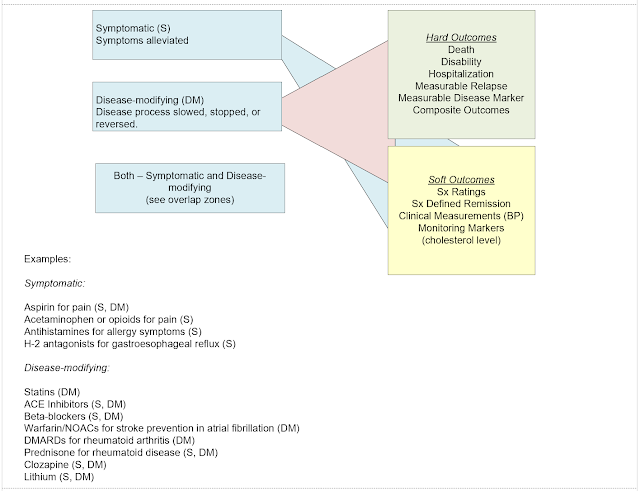

My last post was not satisfactory after I read thorough it

several times. I decided to diagram the

concepts of symptomatic and disease modifying with the suggested parameters and

cite a few specific examples in the diagram.

An obvious problem with the definitions as used by Professor Ghaemi is

that it involved a lot of inductive reasoning on the pathophysiology side of

the equation.

How can you say a medication is affecting underlying

pathophysiology if it is unknown? Much

pathophysiology of complex disease is at the hypothetical rather than

theoretical level. The hypotheses are restated over time, but there are no widely

accepted theories. That has resulted in measurable proxies for pathophysiology

being used like serum biomarkers for rheumatological disease and brain plaques

for active disease and remissions in multiple sclerosis.

The problem with that approach is highlighted with the

recent controversy in the FDA approval of aducanumab ( an anti-beta~amyloid antibody) for Alzheimer’s Disease or mild

cognitive impairment. The biomarker of

PET visualized beta~amyloid plaques were significantly improved in two clinical

trials relative to placebo. Both of

these trials were terminated early when it became apparent, they would not

reach primary efficacy endpoints. In this case, the drug did not reach clinical

efficacy as a disease-modifying drug and it is effective against a biomarker

that may not be a true marker of the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s

Disease. Additionally, the drug was

associated with amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) at a significantly

higher rate than placebo. These lesions

were thought to represent vasogenic edema and microhemorrhages and necessitate

careful screening at baseline for preexisting vascular disease.

There are biases in the literature on where

the term was used. Disease-modifying

seems to be associated primarily with rheumatological and some specific

illnesses like multiple sclerosis. In

other areas it is mentioned primarily as an absence as in: “there are no

disease-modifying drugs for this condition”.

What are the main points that I tried to incorporate into the diagram?

1. Neither the disease-modifying or symptomatic interventions are 100% effective. With any complex, polygenic illness there will be non-responders, partial responders, and optimal responders. In many studies the optimal responders will meet study criteria for remission – but that also happens in clinical practice. For example, it is common to assess people undergoing antidepressant treatment and find that from a subjective standpoint their depressive symptoms are gone and they feel like they are back at their baseline. Of course, in randomized clinical trials there is an intent-to-treat analysis that counts study drops outs in the denominator no matter what the cause. In clinical practice that group would be provided with an alternate treatment.

2. There can be overlap between disease-modifying and symptomatic treatment. There are a few examples in the graphic, but prednisone for rheumatoid arthritis is probably the best example. It treats acute joint and systemic inflammation while preventing bone erosion early in the course of illness. There are many drugs that are either symptomatic or disease-modifying.

3. Many of the

outcomes are not cleanly separable.

Symptom ratings and symptom defined remission can be associated with

hospitalizations, disease markers, and composite outcomes. Measurable disease

markers or biomarkers are certainly preferable, but as noted in the case of

aducanumab there may be unexpected findings suggesting other important

underlying pathophysiology. In the case

of complex diseases we are learning more and more that many genes and many gene

networks are potentially involved. In

that case – a final common pathway or a parsimonious analysis should not be

expected. We appear to be at the very

early stages of being able to analyze these complex interactions.

No matter how you parse it – the definitions considered

above do not allow for a very clearly defined category of disease-modifying and

symptomatic. Does regulatory language

from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the European Medicines Agency

(EMA) help? The standard for disease-modifying

approvals apparently changed before 2019 (2).

Up until that time the standards were largely descriptive like delaying

disability or slowing the progress of illness.

The authors note an uneven approach to the term disease-modifying with

a tendency to use it in rheumatic diseases but less so in neurodegenerative

diseases. They attribute that to disease-modifying being an inferential

concept because “changes in the brain cannot be directly observed”.

This is an important concept because it applies to all of

the hypothetical mechanisms of action of most drugs that exist. In the previous post I pointed out that all

of the disease modifying drugs for multiple sclerosis have no widely accepted

theories about their mechanism of action.

The hypotheses may be listed but more commonly are listed as unknown or

not fully understood. The same is true

for the disease-modifying drugs in psychiatry listed by Ghaemi in his recent

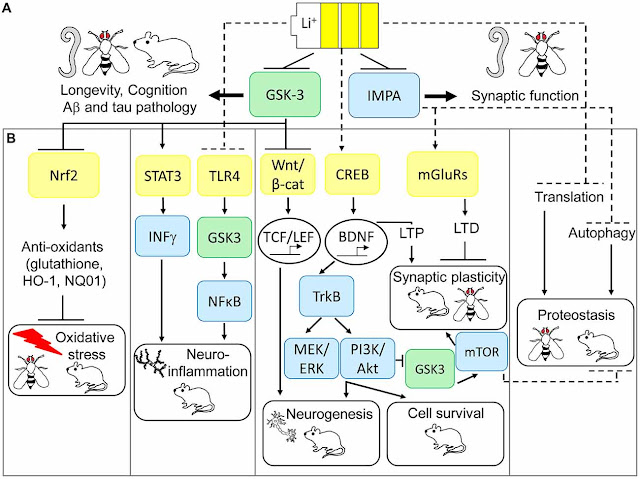

paper (4). Various signaling systems are

cited, but the reality is there is no widely accepted mechanism of action and

more importantly no mechanistic way to explain lithium nonresponse.

The best way to approach disease-modifying drugs in general

and more specifically in psychiatry is to discuss the hypothetical mechanisms

of action and the implications of those mechanisms. That is the focus of research and the basis

for many purported biomarkers of disease in psychiatry but clearly in many

other fields of medicine. With the advent of genomics we are also witnessing a

necessary paradigm shift away from simple explanations.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

References:

1: Rabinovici GD.

Controversy and Progress in Alzheimer's Disease - FDA Approval of Aducanumab. N

Engl J Med. 2021 Aug 26;385(9):771-774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2111320. Epub 2021

Jul 28. PMID: 34320284.

2: Morant AV,

Jagalski V, Vestergaard HT. Labeling of Disease-Modifying Therapies for

Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front Med (Lausanne). 2019 Oct 17;6:223. doi:

10.3389/fmed.2019.00223. PMID: 31681780; PMCID: PMC6811601.

3: Schubert, K.O.,

Thalamuthu, A., Amare, A.T. et al. Combining schizophrenia and

depression polygenic risk scores improves the genetic prediction of lithium

response in bipolar disorder patients. Transl Psychiatry 11, 606

(2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01702-2

4: Ghaemi SN.

Symptomatic versus disease-modifying effects of psychiatric drugs. Acta

Psychiatr Scand. 2022 Jun 2. doi: 10.1111/acps.13459. Epub ahead of print.

PMID: 35653111

5: Alda M. Lithium

in the treatment of bipolar disorder: pharmacology and pharmacogenetics. Mol

Psychiatry. 2015 Jun;20(6):661-70. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.4. Epub 2015 Feb 17.

PMID: 25687772; PMCID: PMC5125816.

6: Kerr F, Bjedov I

and Sofola-Adesakin O (2018) Molecular Mechanisms of Lithium Action: Switching

the Light on Multiple Targets for Dementia Using Animal Models. Front. Mol.

Neurosci. 11:297. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00297

Graphic Credit:

Reference 6 and the following copyright and Open Access license:

Thanks again for this series of posts George. I respect much of Ghaemi's work but I find his perspective on disease modifying drugs problematic for the reasons you lay out here.

ReplyDelete