The New York Times came out with an article on prolonged grief disorder. I thought I would write about it because in some ways it is a continuation of the criticism that started with the DSM-5 release in 2015. The response to that piece is one of the most read articles on thisblog. As I pointed out in that article and several since, the release of the DSM-5 has been a predicted non-event. There were no scandalous developments based on releasing a document that hardly anyone reads and is not even owned by most of the people who prescribe medications for psychiatric indications – primary care physicians.

The new piece based on the release of DSM5-TR is much more

balanced. A well-known psychiatric

researcher Katherine Shear, MD is quoted as well as an epidemiologist Holly Prigerson,

PhD who discovered data supportive of the diagnosis and studied the reliability

and validity. Paul Appelbaum, MD is the

head of the committee to include new diagnoses in the manual and he also

explains the rationale.

What did I not like about the article? It starts out with the old saw about how the

DSM 5 is sometimes known as psychiatry’s bible. I appreciate the

qualifier but let’s lose the term bible in any reference to the DSM. That descriptor is wrong at several levels –

the most important one being that it is a classification system. Please refer to it as psychiatry’s phone

book or catalogue from now on, even though it is nowhere near as

accurate as a phone book or any commercial catalogue.

The author goes on to describe the inclusion of prolonged

grief disorder into the latest revision of DSM as controversial and then

collects opinions on either side of what I consider to be an imaginary

controversy. Why am I so bold to call this controversy imaginary? Maybe it is not entirely imaginary, but it

certainly is not as big a deal as it is portrayed in the article and here is

why.

The first argument is that including it in the DSM means

that professionals can now bill for it. In fact, all hospitals, clinics, public

payers, and insurance companies require ICD-11 codes and not DSM codes. Granted, the DSM codes are typically

coordinated to match ICD-11 codes but there is not a perfect match. ICD-11 codes are available for free and do

not require a copy of the DSM 5 TR. The diagnosis of prolonged grief

disorder was included in the ICD-11 in 2020 (2) and it is easier to make

the diagnosis. Quoting from reference 2:

“To meet PGDICD-11 criteria one

needs to experience persistent and pervasive longing for the deceased and/or

persistent and pervasive cognitive preoccupation with the deceased, combined

with any of 10 additional grief reactions assumed indicative of

intense emotional pain for at least six months after bereavement. Contrary

to the 5th revision of the Diagnostical and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders [DSM-5; (11)] and

the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases [ICD-10; (12)],

the ICD-11 only uses a typological approach, implying that diagnosis

descriptions are simple and there is no strict requirement for the number of

symptoms one needs to experience to meet the diagnostic threshold.”

The insurance company billing is further complicated by the

fact that there are many other current diagnoses that can be used to treat a

person severely incapacitated over a prolonged or severe course of grief. Per my original blog Paula Clayton, MD

explained this 45 years ago based on her research that also showed a small

percentage of people become depressed during grief and require treatment. A

prolonged grief disorder (PGD) diagnoses is not necessary and, in some cases,

may lead to problems with insurance companies. It is well known that some

insurance companies will not reimburse for some diagnoses that they think do

not require treatment by a mental health provider. What they think of a PGD

diagnosis is unknown at this time.

The second argument is that it may lead to biological

treatments for the disorder. They cite a naltrexone trial for this disorder.

Let me be the first to predict that the naltrexone will probably not work but I

will also point out it is a medication that could be prescribed right now

without putting PGD in the DSM 5 TR. The author states this may set off a

competition among pharmaceutical companies for effective medications. That may

be true – but what will the likely outcome be?

We already know that many people with PGD actually have treatable

depression and respond to conventional treatments. We also know that those

medications are all generics, very inexpensive, and the pharmaceutical benefit

managers control most prescriptions for expensive drugs. These factors combined

with the low prevalence of this disorder and well as the responsiveness to psychotherapy

and supportive measure will not produce a windfall for Big Pharma.

There is an inherent bias by some against medical

interventions for any disorder that seems to start out as a phenomenon seemingly

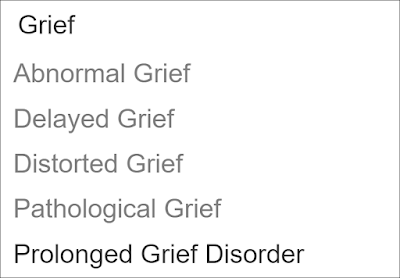

explained by social or psychological factors. Grief was listed as one of the

four major causal factors for depression in Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT)

and there were no complaints. IPT has

been around for 40 years. Is that because the treatment emphasized was

psychotherapy? Throughout my career I

have always had resources available for people who were grieving. Clergy are a

professional resource but with the continued secularization of the country it

is common to find that most people do not have an identifiable clergy person.

Grief support groups are very common – both as self-help groups and groups run

by professionals. The question is what if those resources are not enough to assist

the grieving person?

The third argument is that there will be “false positives”

or people given the diagnosis when they are emerging from the symptoms. That

supposes that the doctor has no discussion with the patient about what might be

helpful including non-medical supportive measures and watchful waiting. It also

supposes that the patient’s interest in what is happening with them

specifically how it is affecting their life and whether they want to do

anything about it is never discussed. I

don’t think most doctors – even if they are in a hurry operate that way.

The fourth argument is the danger of making a diagnosis and

how that impacts the person. Grief is a universal phenomenon that everyone

experiences many times in their life. Everyone knows that through experience. Empathically

discussing with a person that this episode of grief is affecting them differently

than others does not seem to be discounting or minimizing their emotions or

experience to me. The very definition of empathy is that the patient agrees

with the empathic statements as adequately explaining their experience.

A fifth argument buried in there is that clinician want to

rapidly classify people so that they can get reimbursement. I have already

addressed each half of that argument about but let me add – does naming a

disorder mean that it did not exist before? There are thousands of examples in medicine

and psychiatry of new diagnoses that basically classify earlier conditions

where the diagnosis was never made before. A striking example from psychiatry

is autoimmune encephalitis. It was

previously misdiagnosed as either a psychosis or bipolar disorder until the

actual diagnosis was discovered. Rapid classification leads to many paths other

than reimbursement. In the case of autoimmune encephalitis – life saving

treatment.

The fundamental problem in writing articles about human

biology from a political perspective is that it fails to address the biology. The

biology I am referring to here are unique human conscious states and all of the

associated back up mechanisms that make them more or less resilient,

intelligent, and creative. Is the general classification “grief” likely to

capture a large enough number of possibilities to qualify as a rigorous definition?

We have known for some time that is not supported by the empirical evidence and

that evidence has become more robust over the past 20 years. A small number of

people experiencing grief will have a much more difficult time recovering and,

in some case, will not recover without assistance. In spite of that, there

remain biases against studies that focus on elucidating biological mechanisms

or treatments. It is easier to invoke emotional

rhetoric like medicalization or psychiatrization and try to avoid the issue. To the author’s credit none of those terms

were used.

There is also the issue of what this new diagnosis suggests

in terms of the science of psychopathology. Does this mean we are closer to

classifying all of the possible problems of the human psyche and developing

treatments? It reminds me of what one of my psychoanalyst supervisors used to

say about the state of the art. In those

days there were basically biological psychiatrists and psychotherapists.

He referred to anyone without a comprehensive formulation of the patient’s

problem as a dial twister. Are we closer to becoming dial twisters? I have some concerns about the checklist

approach associated with the diagnosis and its understudied phenomenology. That

is compounded by the limited time clinicians have to see patients these days

and the predictable electronic health record templates with minimal typing of

formulations.

Practical considerations aside only time will tell if the

new research leads to better identification and treatment of people with clear

complications of grief. That does not mean that science has all of the answers.

It should be clear that the science of prolonged grief disorder like most of

psychiatry only deals with the severe aspects of human experience. There are clearly other ways to conceptualize

grief and learn about it without science. The science is useful for mental

health practitioners charged with providing treatments to the severely distressed and with grief the vast majority of people (90+%) will never see a practitioner and even fewer than that will ever see a psychiatrist.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

1: Ellen Berry. How Long Should It Take to Grieve? Psychiatry

Has Come Up With an Answer. NY Times March 18,2022.

2: Eisma MC, Rosner

R, Comtesse H. ICD-11 Prolonged Grief Disorder Criteria: Turning Challenges

Into Opportunities With Multiverse Analyses. Front Psychiatry.

2020;11:752. Published 2020 Aug 7. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00752

Excerpted per open-access article distributed under the

terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).

3: Prigerson HG,

Horowitz MJ, Jacobs SC, Parkes CM, Aslan M, et al.

(2013) Correction: Prolonged Grief Disorder: Psychometric Validation of

Criteria Proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLOS

Medicine 10(12): 10.1371/annotation/a1d91e0d-981f-4674-926c-0fbd2463b5ea.

4: Lenferink LIM,

Eisma MC, Smid GE, de Keijser J, Boelen PA. Valid measurement of DSM-5 persistent

complex bereavement disorder and DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 prolonged grief disorder:

The Traumatic Grief Inventory-Self Report Plus (TGI-SR+). Compr Psychiatry.

2022 Jan;112:152281. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2021.152281. Epub 2021 Oct 21.

PMID: 34700189.

5: Shear MK,

Reynolds CF, Simon NM, Zisook S. Prolonged grief disorder in adults:

Epidemiology, clinical features, assessment, and diagnosis. In Peter P

Roy-Byrne and D Solomon (eds) UpToDate https://www.uptodate.com/contents/prolonged-grief-disorder-in-adults-epidemiology-clinical-features-assessment-and-diagnosis#H210445955

accessed on 03/21/2022

6: Klerman GL,

Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES.

Interpersonal Therapy of Depression.

Basic Books, New York, 1984.

7: Ratcliffe M. Towards

a phenomenology of grief: Insights from Merleau-Ponty. European Journal of Philosophy 2019; 28:

657-669 DOI: 10.1111/ejop.12513

8: Clayton PJ. Bereavement in Handbook of Affective of Disorders. Eugene S. Paykel (ed). The Guilford Press. New York. 1982 pages 413-414

Supplementary 1:

Quote from an initial post on this subject 9 years ago as written by Paula Clayton, MD:

"There are many publications that deal with treating psychiatric patients who report recent and remote bereavement. It is possible to find a real or imagined loss in every patient's past. However, for the most part, because there is little evidence from reviewing normal bereavement that there is a strong correlation between bereavement and first entry into psychiatric care, those bereaved who are seen by psychiatrists should be treated for their primary symptoms. This is not to say that the death should not be discussed, but because these people represent a very small subset of all recently bereaved, they should be treated like other patients with similar symptoms but no precipitating cause. A physician seeing a recently bereaved with newly discovered hypertension might delay treatment one or two visits to confirm its continued existence, but treat it if it persists. So the psychiatrist should treat the patient with affective symptoms with somatic therapy but only if the symptoms are major and persist unduly. A careful history of past and present drug and alcohol intake is indicated. Then, the safest and most appropriate drugs to use are the antidepressants. Electroconvulsive therapy is indicated in the suicidal depressed." (Paykel p413-414)