Well known neurologist and author Oliver Sacks has written an essay in the New Yorker about his drug experiences in the 1960s. From about 1963-1967 Dr. Sacks ingested various compounds including cannabis, amphetamines, intravenous morphine, LSD, morning glory seeds, Artane (trihexyphenidyl hydrochloride) and massive doses of chloral hydrate with an accompanying withdrawal state. He does an excellent job of describing various intoxication and delirium states. As an example he describes his experience reading a text on migraines from 1873 while taking amphetamine:

"...In a sort of catatonic concentration that in 10 hours I scarcely moved a muscle or wet my lips, I read steadily through "Megrim"....At times I was unsure if I was reading the book or writing it...." p. 47

In my current professional iteration as an addiction psychiatrist these are familiar scenarios. At some level Sacks realizes that he is lucky to have survived chloral hydrate withdrawal induced delirium tremens and amphetamine-induced tachycardia up to the 200 beats per minute range with an unknown blood pressure. Vivid visual and auditory hallucinations and a distorted sense of time are described. There is also the familiar interpersonal dimension that gets activated when a person's life is affected by drug use - concerned colleagues that implore him to seek help and take care of himself.

Dr. Sacks is an intellectual and this is presented in an intellectual context that may not have been very evident at the time of the experimentation. He describes the sociocultural antecedents of a need for chemical transcendance that has been present throughout human history. He proceeds to describe some of the relevant historical writings of physicians and other intellectuals.

The usual debate about whether or not there is any utility in taking life threatening amounts of drugs occurs in the text and on the podcast. Not surprisingly, intellectuals derive insights from their experiences and taking drugs is no exception. In the article, the revolution in neurochemistry was one of the preludes to the period of experimentation. The problems with psychotic symptoms and manic states are well described as well as what states might be the preferred ones. We learn on the podcast that these experiences have provided insights into possible brain mechanisms and that this might be part of the basis for the author's new book Hallucinations that comes out in the fall.

Dr. Sacks describes himself as an observer and explorer of psychotic symptoms and how that seems to be protective when he is tripping. What is missing here compared to the people I have talked with is a highly subjective response that increases the risk for drug use. I typically hear about intense euphoria, high energy, and increased competence in physical, intellectual and social spheres. Not having that response may be protective and may allow one to avoid the risks of ongoing chemical use. In some cases there may just be a compulsion to recreate the drug induced state. The essay may have been a lot more complicated or written by someone else if those descriptions were there.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

Oliver Sacks. Altered States - Self experiments in chemistry. The New Yorker, August 27, 2012: 40-47.

Oliver Sacks. Podcast: The New Yorker Out Loud.

Saturday, September 1, 2012

Friday, August 24, 2012

Lance Armstrong and parallels with physician discipline

I read the headlines in the paper today "Armstrong stripped of seven Tour titles." I had just read his personal position on Facebook. For those who have not followed this issue, the US Anti Doping Agency (USADA) has been trying to say that Armstrong violated doping regulations by using banned substances despite a significant amount of objective evidence in his favor. The objective evidence in his favor was to such a degree that the Department of Justice dropped a 2 year investigation of him. The USADA is not a branch of law enforcement branch but it does have the power to ban athletes, ban them for life, and apparently remove any awards that they have won in a retrospective manner even though they were under intense scrutiny at the time. In my reading the USADA also apparently believes that their test results are infallible which makes their spin on those results even more confusing. As Armstrong points out - during competition he had to submit for testing 24/7 at at no time did the USADA say that he had a positive test result or pull him from competition. I am not going to review the pros and cons of the decision - only to say that at this point it has been politicized and a stunning amount of objective evidence has been ignored. My interest in the process is how it resembles similar processes that are conducted against physicians.

The "disruptive physician" concept seems to have been the driving force behind a lot of these initiatives. Disruptive physicians to me would be physicians who have not violated the medical practice statutes in their states. They would be basically physicians that somebody doesn't like because of their behavior or personality. The Joint Commission has a position statement:

The "disruptive physician" concept seems to have been the driving force behind a lot of these initiatives. Disruptive physicians to me would be physicians who have not violated the medical practice statutes in their states. They would be basically physicians that somebody doesn't like because of their behavior or personality. The Joint Commission has a position statement:

"Intimidating and disruptive

behaviors including overt actions such as verbal outbursts and physical

threats, as well as passive activities such as refusing to perform assigned

tasks were quietly exhibiting uncooperative attitudes during routine

activities. Intimidating and disruptive behaviors are often manifested by

healthcare professionals in positions of power. Such behaviors include

reluctance or refusal to answer questions, return phone calls or pages,

condescending language or voice intonation, and impatience with questions or it

overt and passive behaviors undermine team effectiveness and can compromise the

safety of patients. All intimidating and disruptive behaviors are

unprofessional and should not be tolerated."

They go on to cite research suggesting that these behaviors are widespread as high as 40% in some settings. The research is survey research and there are no concerns about its potential quality or biases. My concern and working in a number of medical settings for the past 30 years is that I have witnessed it exactly once. An attending physician personally verbally attacked me several times after he learned I was going to be a psychiatrist at least until I outguessed him on the correct diagnosis of acute abdominal pain. I think that behavior would clearly qualify.

On the other hand, I have become aware of many physicians being disciplined and even losing their jobs over trivial situations in the workplace. Apparently the threshold for a complaint against a physician is that the complainant feels as if they were "disrespected". In today's healthcare environment that complaint plus a personal dislike from a department chairman is enough to get you fired or at least live a miserable existence until you decide to quit. That is true irrespective of the number of people who would testify on your behalf, service to the department, patient satisfaction ratings, ratings by residents and medical students, and other professional accomplishments. If you are a physician these days all it takes is the subjective opinion from someone who does not know you or your personal motivation or reasons for doing things to file a complaint and potentially destroy your career. Even if you are not fired outright, there could be a lingering process of accumulating demerits and reviews by other physicians who are not sympathetic to your plight before you are ultimately let go.

At least Lance Armstrong can say that a ton of objective evidence was ignored in order to make this decision. The decision against a physician can be based on a single subjective complaint irrespective of how reliable or credible the complainant is and what sort of evidence exists.

That is all it takes to be a disruptive physician.

That is all it takes to be a disruptive physician.

George Dawson, MD. DFAPA

Monday, August 20, 2012

AMA, DOJ, and managed care all on the same side?

That's right and they are all potentially aligned against doctors.

The lesson from the 1990's and again in the early 20th century was that politicians who were not competent to address health care reform in any functional way could come up with all sorts of off-the-wall-theories. One of the most off-the-wall theories was that widespread health care fraud was a major cause of health care inflation. It stands to reason if that is the case that is true, the perpetrators would be easy to find and put out of business. To borrow typical language of the Executive branch it was a War on Healthcare Fraud.

To anyone who did not endure it, it is now a well kept secret. The tactics of the government used in those days - entering clinics and doctors offices in an intimidating manner and taking out boxes and boxes of charts for review by special agents who were "coding experts" and then assigning some tremendous fine based on alleged "fraud" have been expunged from most places. I sent two Freedom of Information Act requests to involved federal agencies and was told that information "did not exist" even after I provided the front page from one of the documents with the name of the agency.

It was quite a spectacle and it had doctors everywhere running scared. After all, the interpretation of notes and linking them to billing documents was entirely subjective. If a handful of notes was reviewed and bills were actually sent through the mail - racketeering charges via RICO statutes were possible and the fines would skyrocket to the point that nobody could ever pay them. Federal prison was a possibility. All for having a deficient note?

What followed was a carefully orchestrated set of maneuvers to render beleaguered physicians even weaker. A decade of millions and millions of hours wasted on worthless documentation out of paranoia of a government audit. Whose notes actually "fit" the government criteria? The notes varied drastically from clinic to clinic and year to year in the same clinic. And then a masterful stroke. The government probably realized that their micromanagement of progress notes as leverage against physician productivity was probably undoable. It would take far more agents than the budget would allow and they would no longer be able to demonstrate "cost effectiveness" in terms of recovered funds on the DOJ web site.

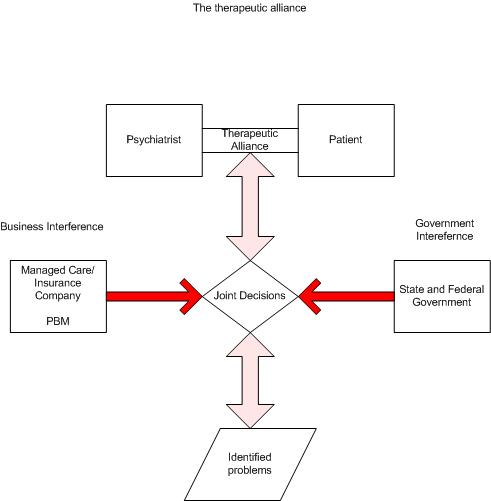

At that point they were able to turn this political device over to managed care companies who could selectively apply it anyway they wanted. Some physicians noted that their documentation and coding scores by internal audit could be the best in the organization one year and the worst then next even though they had not changed any of their paperwork practices. These audits to assure compliance with federal guidelines quickly became a mechanism for managed care organization (MCOs) to deny payment and "downcode" a practitioner's billing based on their review of chart notes. Incredibly the MCO could deny payment for a block of billing submitted or pay much less than what was submitted. Where else in our society can you decide to pay whatever you want for a service rendered? That is the kind of power that the government gives MCOs.

Enter the new "partnership" to deal with health care fraud. It is basically a coalition of the same players who have been using the health care fraud rhetoric for the past 20 years. The DOJ, FBI, HHS OIG, large insurance companies and managed care corporations. This quote says it all:

"The joint effort acknowledges the limitations of each health care insurer relying solely on its own data and fraud prevention techniques. After a 2010 summit, 21 private payers and government agencies discovered that they were victims of the same scams. As a result, the participants pledged to ban together against fraud."

The HHS Secretary chimed in:

"This partnership puts criminals on notice that we will find them and stop them before they steal health care dollars."

The newly elected psychiatrist-AMA president Jeremy Lazarus advises:

"Claims coding and documentation involve complicated clinical issues and the analysis of these claims requires the clinical lens of physician education and training."

Good luck with that Dr. Lazarus and heaven help any physician who gets caught under the managed care-federal government juggernaut. And who protects physicians against those who are defrauding them by non payment or trivial payment for services rendered based on a totally subjective interpretation of a chart note? Nobody I guess. I guess we will continue to deny that is possible and a common occurrence.

This can only happen in a country where the government provides businesses with every possible bit of leverage against physicians and where most political theories about health care reform are pure fantasy.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

Charles Feigl. New public-private partnership targets health fraud. AMNews August 20, 2012.

The lesson from the 1990's and again in the early 20th century was that politicians who were not competent to address health care reform in any functional way could come up with all sorts of off-the-wall-theories. One of the most off-the-wall theories was that widespread health care fraud was a major cause of health care inflation. It stands to reason if that is the case that is true, the perpetrators would be easy to find and put out of business. To borrow typical language of the Executive branch it was a War on Healthcare Fraud.

To anyone who did not endure it, it is now a well kept secret. The tactics of the government used in those days - entering clinics and doctors offices in an intimidating manner and taking out boxes and boxes of charts for review by special agents who were "coding experts" and then assigning some tremendous fine based on alleged "fraud" have been expunged from most places. I sent two Freedom of Information Act requests to involved federal agencies and was told that information "did not exist" even after I provided the front page from one of the documents with the name of the agency.

It was quite a spectacle and it had doctors everywhere running scared. After all, the interpretation of notes and linking them to billing documents was entirely subjective. If a handful of notes was reviewed and bills were actually sent through the mail - racketeering charges via RICO statutes were possible and the fines would skyrocket to the point that nobody could ever pay them. Federal prison was a possibility. All for having a deficient note?

What followed was a carefully orchestrated set of maneuvers to render beleaguered physicians even weaker. A decade of millions and millions of hours wasted on worthless documentation out of paranoia of a government audit. Whose notes actually "fit" the government criteria? The notes varied drastically from clinic to clinic and year to year in the same clinic. And then a masterful stroke. The government probably realized that their micromanagement of progress notes as leverage against physician productivity was probably undoable. It would take far more agents than the budget would allow and they would no longer be able to demonstrate "cost effectiveness" in terms of recovered funds on the DOJ web site.

At that point they were able to turn this political device over to managed care companies who could selectively apply it anyway they wanted. Some physicians noted that their documentation and coding scores by internal audit could be the best in the organization one year and the worst then next even though they had not changed any of their paperwork practices. These audits to assure compliance with federal guidelines quickly became a mechanism for managed care organization (MCOs) to deny payment and "downcode" a practitioner's billing based on their review of chart notes. Incredibly the MCO could deny payment for a block of billing submitted or pay much less than what was submitted. Where else in our society can you decide to pay whatever you want for a service rendered? That is the kind of power that the government gives MCOs.

Enter the new "partnership" to deal with health care fraud. It is basically a coalition of the same players who have been using the health care fraud rhetoric for the past 20 years. The DOJ, FBI, HHS OIG, large insurance companies and managed care corporations. This quote says it all:

"The joint effort acknowledges the limitations of each health care insurer relying solely on its own data and fraud prevention techniques. After a 2010 summit, 21 private payers and government agencies discovered that they were victims of the same scams. As a result, the participants pledged to ban together against fraud."

The HHS Secretary chimed in:

"This partnership puts criminals on notice that we will find them and stop them before they steal health care dollars."

The newly elected psychiatrist-AMA president Jeremy Lazarus advises:

"Claims coding and documentation involve complicated clinical issues and the analysis of these claims requires the clinical lens of physician education and training."

Good luck with that Dr. Lazarus and heaven help any physician who gets caught under the managed care-federal government juggernaut. And who protects physicians against those who are defrauding them by non payment or trivial payment for services rendered based on a totally subjective interpretation of a chart note? Nobody I guess. I guess we will continue to deny that is possible and a common occurrence.

This can only happen in a country where the government provides businesses with every possible bit of leverage against physicians and where most political theories about health care reform are pure fantasy.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

Charles Feigl. New public-private partnership targets health fraud. AMNews August 20, 2012.

Thursday, August 16, 2012

Violence Prevention - Is The Scientific Community Finally Getting It?

I have

been an advocate for violence prevention including mass homicides and mass

shootings for many years now. It has involved

swimming upstream against politicians and the public in general who seem to

believe that violence prevention is not possible. A large part of that attitude is secondary to

politics involved with the Second Amendment and a strong lobby from firearm advocates. My position has been that you can study the

problem scientifically and come up with solutions independent of the firearms

issue based on the experience of psychiatrists who routinely treat people who

are potentially violent and aggressive.

I was

very interested to see the editorial in this week's Nature advocating the scientific study of mass homicides and

firearm violence. They make the interesting observation that one media story

referred to one of the recent perpetrators as being supported by the United States

National Institutes of Health and somehow implicating that agency in the

shooting spree and that:

"In this climate,

discussions of the multiple murders sounded all too often like descriptions of

the random and inevitable carnage caused by a tornado or earthquake".

Even

more interesting is the fact that the National Rifle Association began a

successful campaign to squash any scientific efforts to study the problem in

1996 when it shut down a gun violence research effort by the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention. The authors go on to list two New England

Journal of Medicine studies from that group that showed a 2.7 fold greater risk

of homicide in people living in homes where there was a firearm and a 4.8 fold

greater risk of suicide. Even worse:

"Congress

has included in annual spending laws the stipulation that none of the CDC's

injury prevention funds "may be used to advocate or promote gun

control"."

This

year the ban was extended to all agencies of the Department of Health and Human

Services including the NIH. There is

nothing like a gag order on science based on political ideology.

The

authors conclude by saying that rational decisions on firearms cannot occur in

a "scientific vacuum". That

is certainly accurate from both a psychiatric perspective and the firearms

licensing and registration perspective. Based on their responses to the most

recent incidents it should be clear that politicians are not thoughtful about

this problem and they certainly have no solutions. We are well past time to

study this problem scientifically and start to design approaches to make mass

shootings a problem of the past rather than a frequently recurring problem.

George

Dawson, MD, DFAPA

Who

calls the shots? Nature. 2012 Aug 9;488(7410):129. doi: 10.1038/488129a. PubMed

PMID: 22874927.

Saturday, August 11, 2012

DSM5 Dead on Arrival!

That's right. The latest sensational blast on the fate of that darling of the media the DSM5 is that it is dead on arrival. That recent proclamation is from the Neuroskeptic and it is based on the analysis of criticism of DSM5 criteria for Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). OK - the original proclamation was "increasingly likely DOA". I confess that at this point I have not read the original article by Starcevic, Portman, and Beck but the Neuroskeptic provides significant excerpts and analysis.

The broad criticism is that the category has been expanded and is therefore less specific. The authors are concerned that this will lead to more inclusion and that will have "negative consequences." The main concern is the "overmedicalization" of the worried and the dilution of clinical trails. All this gnashing of the teeth leads me to wonder if anyone has actually read the Generalized Anxiety Disorder DSM5 criteria that is available on line. The proposed new criteria, the old DSM-IV criteria and the rationale for the changes are readily observed. The basic changes include a reduction on the time criteria for excessive worry from 6 months to three months, the elimination of criteria about not being able to control worry, and the elimination of 4/6 symptoms under criteria C (easy fatigue, difficulty concentrating, irritability and sleep disturbance). A new section on associated behaviors including avoidance behavior a well known feature of anxiety disorders is included. The remaining sections on impairment and differential diagnosis are about the same. The GAD-7 is included as a severity measure although I note that the Pfizer copyright is not included.

So what about all of the criticism? The "Rationale" tab is a good read on the DSM5 web site. I can say that clinically non-experts are generally clueless about the DSM-IV features of anxiety especially irritability. Most psychiatrists have a natural interest in irritability because we tend to see a lot of irritable people. There has been some isolated work on irritability but it really has not produced much probably because it is another nonspecific symptoms that cuts across multiple categories like the authors apply to cognitive problems and pain. So I will miss irritability but not much. Psychiatrists have to deal with it whether we have a category for it or not and hence the need for a diagnostic formulation in addition to a DSM diagnosis (managed care time constraints permitting).

But like most things psychiatric - the worried masses rarely present to psychiatrists for treatment these days. How likely is it that a busy primary care physician is going to review ANY DSM criteria for GAD? How likely is it that a person with a substance abuse disorder is going to disclose those details to a primary care physician as a probable cause of their anxiety disorder? How likely is it that benzodiazepines will be avoided as a first line treatment for any anxiety disorder? In my experience as an addiction psychiatrist I would place the probability in all three questions to be very low. It doesn't really matter if you use DSM-IV criteria or DSM5 criteria - the results are the same.

As far as "medicalization" goes, I am sure that somebody (probably on the Huffington Blog) will whip this into another rant about how the DSM5 enables psychiatrists to overdiagnose and overprescribe in our role as stooges for Big Pharma. But who really has an interest in treating all anxiety like a medical problem? I have previously posted John Greist's single handed efforts in promoting psychotherapy and computerized psychotherapy for anxiety disorders even to the point of saying that the results are superior to pharmacotherapy. In the meantime, what has the managed care cartel been doing? Although their published guidelines appear to be nonexistent it would be difficult to not see the parallels between approaches that use the PHQ-9 to assess and treat depression and using the parallel instrument GAD-7 in a similar manner. The problem with both approaches is that they are acontextual and the severity component cannot be adequately assessed. The goal of managed care approaches to treat depression is clearly to get as many people on medications as possible and call that adequate treatment. Why would the treatment of GAD be any different?

It should be obvious at this point that I am not too concerned about the DSM5, DSM-IV, or whatever diagnostic system somebody wants to use. The DSM5 is clearly about rearranging criteria based on recent studies with the sole exception of including valid biological markers for the sleep disorders section. Like many my speculation is that the ultimate information based approach to psychiatric disorders rests in genomics and refined epigenetic analysis and I look forward to that information being incorporated at some point along the way.

But let's get realistic about why the results of DSM technology are limited. As it is with DSM-IV and as it will be with DSM5, clinicians are free to interpret and diagnose basically whatever they want. Even with the vagaries of a DSM diagnosis, I doubt that the majority of primary care treatment hinges on a DSM diagnosis of any sort. I also doubt that the dominant managed care approach to diagnosis and treatment of GAD depends on a psychiatric diagnosis or research based treatment. It certainly excludes psychotherapy. Trying to pin those serious deficiencies as well as overexposure to medication on the DSM and psychiatrists is folly.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

1: Gorman JM. Generalized anxiety disorders. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987; 22: 127-40. PubMed PMID: 3299062.

The broad criticism is that the category has been expanded and is therefore less specific. The authors are concerned that this will lead to more inclusion and that will have "negative consequences." The main concern is the "overmedicalization" of the worried and the dilution of clinical trails. All this gnashing of the teeth leads me to wonder if anyone has actually read the Generalized Anxiety Disorder DSM5 criteria that is available on line. The proposed new criteria, the old DSM-IV criteria and the rationale for the changes are readily observed. The basic changes include a reduction on the time criteria for excessive worry from 6 months to three months, the elimination of criteria about not being able to control worry, and the elimination of 4/6 symptoms under criteria C (easy fatigue, difficulty concentrating, irritability and sleep disturbance). A new section on associated behaviors including avoidance behavior a well known feature of anxiety disorders is included. The remaining sections on impairment and differential diagnosis are about the same. The GAD-7 is included as a severity measure although I note that the Pfizer copyright is not included.

So what about all of the criticism? The "Rationale" tab is a good read on the DSM5 web site. I can say that clinically non-experts are generally clueless about the DSM-IV features of anxiety especially irritability. Most psychiatrists have a natural interest in irritability because we tend to see a lot of irritable people. There has been some isolated work on irritability but it really has not produced much probably because it is another nonspecific symptoms that cuts across multiple categories like the authors apply to cognitive problems and pain. So I will miss irritability but not much. Psychiatrists have to deal with it whether we have a category for it or not and hence the need for a diagnostic formulation in addition to a DSM diagnosis (managed care time constraints permitting).

But like most things psychiatric - the worried masses rarely present to psychiatrists for treatment these days. How likely is it that a busy primary care physician is going to review ANY DSM criteria for GAD? How likely is it that a person with a substance abuse disorder is going to disclose those details to a primary care physician as a probable cause of their anxiety disorder? How likely is it that benzodiazepines will be avoided as a first line treatment for any anxiety disorder? In my experience as an addiction psychiatrist I would place the probability in all three questions to be very low. It doesn't really matter if you use DSM-IV criteria or DSM5 criteria - the results are the same.

As far as "medicalization" goes, I am sure that somebody (probably on the Huffington Blog) will whip this into another rant about how the DSM5 enables psychiatrists to overdiagnose and overprescribe in our role as stooges for Big Pharma. But who really has an interest in treating all anxiety like a medical problem? I have previously posted John Greist's single handed efforts in promoting psychotherapy and computerized psychotherapy for anxiety disorders even to the point of saying that the results are superior to pharmacotherapy. In the meantime, what has the managed care cartel been doing? Although their published guidelines appear to be nonexistent it would be difficult to not see the parallels between approaches that use the PHQ-9 to assess and treat depression and using the parallel instrument GAD-7 in a similar manner. The problem with both approaches is that they are acontextual and the severity component cannot be adequately assessed. The goal of managed care approaches to treat depression is clearly to get as many people on medications as possible and call that adequate treatment. Why would the treatment of GAD be any different?

It should be obvious at this point that I am not too concerned about the DSM5, DSM-IV, or whatever diagnostic system somebody wants to use. The DSM5 is clearly about rearranging criteria based on recent studies with the sole exception of including valid biological markers for the sleep disorders section. Like many my speculation is that the ultimate information based approach to psychiatric disorders rests in genomics and refined epigenetic analysis and I look forward to that information being incorporated at some point along the way.

But let's get realistic about why the results of DSM technology are limited. As it is with DSM-IV and as it will be with DSM5, clinicians are free to interpret and diagnose basically whatever they want. Even with the vagaries of a DSM diagnosis, I doubt that the majority of primary care treatment hinges on a DSM diagnosis of any sort. I also doubt that the dominant managed care approach to diagnosis and treatment of GAD depends on a psychiatric diagnosis or research based treatment. It certainly excludes psychotherapy. Trying to pin those serious deficiencies as well as overexposure to medication on the DSM and psychiatrists is folly.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

1: Gorman JM. Generalized anxiety disorders. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987; 22: 127-40. PubMed PMID: 3299062.

Friday, August 10, 2012

Managed Care - A Variant of Looterism?

I follow several economic and financial blogs and I came across this piece on looterism yesterday. For those of you not interested in clicking on the blog post, looterism is defined as maximizing private benefit irrespective of a goal of creating value or "private benefit regardless of the damage." The author is focused on economic examples like banking corruption. If you actually follow the politics and corruption in our financial system there turn out to be endless examples. Dao references an earlier paper that nicely describes the current dynamic of maximizing extractable value rather than net economic worth so that the current creditors are left holding the bag.

I can't think of better example of looterism than managed care. Starting at the top end, what exactly occurs when a managed care company decides that they are not going to pay for an inpatient hospitalization for a patient with suicidal thinking. It gets more complicated in a hurry if that person has no housing, a history of actual suicide attempts, and a substance abuse problem. What happens if they say that they can be seen in an outpatient visit despite the fact that visit is two weeks away and it will involve a 15 minute conversation and a prescription that also may not be covered by the managed care company? I am a psychiatrist - so all of these denials are abhorrent to me, but what is the economic analysis of this situation?

The economic analysis is straightforward. The managed care company is not creating any value. Their product is supposed to be patient care and the situation as I described it is anything but patient care. Managed care advocates might say they are creating value by being better stewards of the resources. That is quite a stretch when they have essentially destroyed inpatient psychiatric care by promoting their mantra that a person needs to be "dangerous to oneself or others" in order to get admitted. Forget the notion that things are out of control at home and nobody has slept for a week. If the patient doesn't use the suicide word in the emergency department they are not getting in.

That completely artificial barrier to hospitalization has destroyed inpatient psychiatric care as a resource. People come in a crisis and many leave in the same crisis. There is no time for stabilization or a thoughtful analysis of the problem. Short crisis stays and inadequate reimbursement has a corrosive effect on staff morale, resources for the physical plant, and the quality of care delivered. Less and less value is created.

Eventually, staff with expertise can no longer tolerate the environment - especially when they are seeing more people and they are less able to help them given the managed care restraints. These staff leave and move to a more suitable patient care environment. The loss of knowledge workers creates even less value but it is a critical strategy in extracting value from mental health services and putting it somewhere else. If knowledge workers can't be demoralized managed care can always come up with a strategy to simply not pay them or pay them very little. The outpatient equivalent of inpatient care is seeing high volumes of outpatients - often for the sake of producing billing documents. The associated appointments are often low in value.

I would say that looterism is alive and well in the medical industry. You don't have to look very far in the health care economics field or your own health plan. The associated marketing campaigns that talk about high quality care associated with looterism should be cautiously approached. But that is a story for a different day.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

Francisco Dao. Looterism: The Cancerous Ethos That is Gutting America. August 7, 2012.

I can't think of better example of looterism than managed care. Starting at the top end, what exactly occurs when a managed care company decides that they are not going to pay for an inpatient hospitalization for a patient with suicidal thinking. It gets more complicated in a hurry if that person has no housing, a history of actual suicide attempts, and a substance abuse problem. What happens if they say that they can be seen in an outpatient visit despite the fact that visit is two weeks away and it will involve a 15 minute conversation and a prescription that also may not be covered by the managed care company? I am a psychiatrist - so all of these denials are abhorrent to me, but what is the economic analysis of this situation?

The economic analysis is straightforward. The managed care company is not creating any value. Their product is supposed to be patient care and the situation as I described it is anything but patient care. Managed care advocates might say they are creating value by being better stewards of the resources. That is quite a stretch when they have essentially destroyed inpatient psychiatric care by promoting their mantra that a person needs to be "dangerous to oneself or others" in order to get admitted. Forget the notion that things are out of control at home and nobody has slept for a week. If the patient doesn't use the suicide word in the emergency department they are not getting in.

That completely artificial barrier to hospitalization has destroyed inpatient psychiatric care as a resource. People come in a crisis and many leave in the same crisis. There is no time for stabilization or a thoughtful analysis of the problem. Short crisis stays and inadequate reimbursement has a corrosive effect on staff morale, resources for the physical plant, and the quality of care delivered. Less and less value is created.

Eventually, staff with expertise can no longer tolerate the environment - especially when they are seeing more people and they are less able to help them given the managed care restraints. These staff leave and move to a more suitable patient care environment. The loss of knowledge workers creates even less value but it is a critical strategy in extracting value from mental health services and putting it somewhere else. If knowledge workers can't be demoralized managed care can always come up with a strategy to simply not pay them or pay them very little. The outpatient equivalent of inpatient care is seeing high volumes of outpatients - often for the sake of producing billing documents. The associated appointments are often low in value.

I would say that looterism is alive and well in the medical industry. You don't have to look very far in the health care economics field or your own health plan. The associated marketing campaigns that talk about high quality care associated with looterism should be cautiously approached. But that is a story for a different day.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

Francisco Dao. Looterism: The Cancerous Ethos That is Gutting America. August 7, 2012.

Sunday, August 5, 2012

What does the Minnesota bill collecting scandal really mean?

The news this week in Minnesota was that the Attorney General had negotiated a settlement with Accretive Health Care over their collection techniques. When I read the original articles and summaries on the AG's web site, it reminded me of a conversation I had with a psychiatrist many years ago. He was hired by a hospital CEO who told him that he would be responsible for reminding patients that they needed to bring their insurance card for appointments. I thought that was an odd job for a physician but chalked it up to the generally poor level of administrative and clinical support that most psychiatrists get. One of his patients complained to the CEO about this process and he was fired. Another example of medical professionalism being compromised and then scapegoated by business practice.

I encourage anyone with more than a passing interest in just how far business practices have intruded and compromised medical practice to read the scenarios described in this Pioneer Press article. Patient after patient describing a situation where they were confronted bill collectors when they were either critically ill or just before surgery. The article also contain the industry's perspective:

"Point of service collections have become fairly standard practice." (page 6A, par 5)

The bottom line here is that this is really not quite the scandal that the Attorney General and the media are holding it up to be. The reason is very simple. Managed care is the dominant force in health care markets today. They hold that position because politicians in both state and federal governments want them to have that kind of power. As an example, Minnesota Statutes have managed care tactics written into them. These tactics have misplaced any professional input from physicians a long time ago. They use their own standards - many of which are made up within the industry and have no scientific backing. Business entities do not have any ethical standards. The ethics of a business are relative and depend a lot on the executives running it. It is clearly acceptable to confront you for a co-payment or past due bill even if you were too sick to think about picking up your wallet.

There is no reason to expect that these onerous collection practices will not be routine in the future. That should be obvious to anyone who can see that the influence of medicine and medical doctors is at an all time low. We frequently hear from politicians and bureaucrats that physician influence is never coming back and we should all: "Get used to it.". Hoping for a series of activist Attorney Generals is about all that's left.

If you are critically ill and somebody asks you for your charge card and looks irritated when you don't have it - you will have the managed care cartel and the government backing them to thank.

George Dawson, MD. DFAPA

Cristopher Snowbeck. Patients, hospital see lesson in billing furor. Pioneer Press. August 5, 2012.

I encourage anyone with more than a passing interest in just how far business practices have intruded and compromised medical practice to read the scenarios described in this Pioneer Press article. Patient after patient describing a situation where they were confronted bill collectors when they were either critically ill or just before surgery. The article also contain the industry's perspective:

"Point of service collections have become fairly standard practice." (page 6A, par 5)

The bottom line here is that this is really not quite the scandal that the Attorney General and the media are holding it up to be. The reason is very simple. Managed care is the dominant force in health care markets today. They hold that position because politicians in both state and federal governments want them to have that kind of power. As an example, Minnesota Statutes have managed care tactics written into them. These tactics have misplaced any professional input from physicians a long time ago. They use their own standards - many of which are made up within the industry and have no scientific backing. Business entities do not have any ethical standards. The ethics of a business are relative and depend a lot on the executives running it. It is clearly acceptable to confront you for a co-payment or past due bill even if you were too sick to think about picking up your wallet.

There is no reason to expect that these onerous collection practices will not be routine in the future. That should be obvious to anyone who can see that the influence of medicine and medical doctors is at an all time low. We frequently hear from politicians and bureaucrats that physician influence is never coming back and we should all: "Get used to it.". Hoping for a series of activist Attorney Generals is about all that's left.

If you are critically ill and somebody asks you for your charge card and looks irritated when you don't have it - you will have the managed care cartel and the government backing them to thank.

George Dawson, MD. DFAPA

Cristopher Snowbeck. Patients, hospital see lesson in billing furor. Pioneer Press. August 5, 2012.

Saturday, August 4, 2012

"Preventing Violence: Any Thoughts?"

The title of this post may look familiar because it was the title of a recent topic on the ShrinkRap blog. That is why I put it in quotes. I put in a post consistent with some the posts and articles I have written over the past couple of years on this topic. I know that violence, especially violence associated with mental illness can be prevented. It is one of the obvious jobs of psychiatrists and one of the dimensions that psychiatrists are supposed to assess on every one of their evaluations. It was my job in acute care setting for over 25 years and during that time I have assessed and treated all forms of violence and suicidal behavior. I have also talked with people after it was too late - after a homicide or suicide attempt had already occurred.

The responses to my post are instructive and I thought required a longer response than the brief back and forth on another blog. The arguments against me are basically:

1. You not only can't prevent violence but you are arrogant for suggesting it.

2. You really aren't interested in violence prevention but you are a cog machine of the police state and inpatient care is basically an extension of that.

3. You can treat aggressive people in an inpatient setting basically by oversedating them.

4. People who are mentally ill who have problems with violence and aggression aren't stigmatized any more than people with mental illness who are not aggressive.

These are all common arguments that I will discuss in some detail, but there is also an overarching dynamic and that is basically that psychiatrists are arrogant, inept, unskilled, add very little to the solution of this problem and should just keep quiet. All part of the zeitgeist that people get well in spite of psychiatrists not because of psychiatrists. Nobody would suggest that a Cardiologist with 25 years experience in treating acute cardiac conditions should not be involved in discussing public health measures to prevent acute cardiac disorders. Don't tell anyone that you are having chest pain? Don't call 911? Those are equivalent arguments. We are left with the curious situation where the psychiatrist is held to same medical level of accountability as other physicians but his/her opinion is not wanted. Instead we can listen to Presidential candidates and the talking heads all day long who have no training, no experience, no ideas, and they all say the same thing: "Nothing can be done."

It is also very interesting that nobody wants to address the H-bomb - my suggestion that there should be direct discussion of homicidal ideation. Homicidal ideation and behavior can be a symptom. There should be public education about this. Why no discussion? Fear of contagion? Where does my suggestion come from? Is anyone interested? I guess not. It is far easier to continue saying that nothing can be done. The media can talk about sexual behavior all day long. They can in some circumstances talk about suicide. But there is no discussion of violence and aggression other than to talk about what happened and who is to blame. That is exactly the wrong discussion when aggression is a symptom related to mental illness.

So what about the level of aggression that psychiatrists typically contain and what is the evidence that they may be successful. Any acute care psychiatric unit that sees patients who are taken involuntarily to an emergency department sees very high levels of aggression. That includes, threats, assaults, violent confrontations with the police, and actual homicide. The causes of this behavior are generally reversible because they are typically treatable mental illnesses or drug addiction or intoxication states. The news media likes to use the word "antisocial personality" as a cause and it can be, but people with that problem are typically not taken to a hospital. The police recognize their behavior as more goal oriented and they do not have signs and symptoms of mental illness. Once the psychiatric cause of the aggression is treated the threat of aggression is significantly diminished if not resolved.

In many cases people with severe psychiatric illnesses are treated on an involuntary basis. They are acutely symptomatic and do not recognize that their judgment is impaired. That places them at risk for ongoing aggression or self injury. Every state has a legal procedure for involuntary treatment based on that principle. The idea that involuntary treatment is necessary to preserve life has been established for a long time. Civil commitment and guardianship proceedings are recognition that treatment and in some cases emergency placement can be life saving solutions.

The environment required to contain and treat these problems is critical. It takes a cohesive treatment team that understands that the aggressive behavior that they are seeing is a symptom of mental illness. The meaning is much different than dealing with directed aggression by people with antisocial personalities who are intending to harm or intimidate for their own personal gain. That understanding is critical for every verbal and nonverbal interaction with aggressive patients. Aggression cannot be contained if the hospital is run by administrators who are not aware of the cohesion necessary to run these units and who do not depend on staff who have special knowledge in treating aggression. All of the staff working on these units have to be confident in their approach to aggression and comfortable being in these settings all day long.

Medication is frequently misunderstood in inpatient settings. In 25 years of practice it is still very common to hear that medication turns people into "zombies". Comments like: "I don't want to be turned into a zombie" or "You have turned everyone into zombies" are common. I remember the last comment very well because it was made by an observer who was looking at people who were not taking any medication. In fact, medication is used to treat acute symptoms and in this particular case symptoms that increase the risk of aggression. The medications typically used are not sedating. They cannot be because frequent discussions need to occur with the patient and a plan needs to be developed to reduce the risk of aggression in the future. An approach developed by Kroll and MacKenzie many years ago is still a good blueprint for the problem.

There is no group of people stigmatized more than those with mental illness and aggression. It is a Hollywood stereotype but I am not going to mention the movies. This group is also disenfranchised by advocates who are concerned that any focus on this problem will add stigma to the majority of people with mental illness who are not aggressive or violent. There are some organizations with an interest in preventing violence and aggression, but they are rare.

At some point in future generations there may be a more enlightened approach to the primitive thoughts about human consciousness, mental illness and aggression. For now the collective consciousness seems to be operating from a perspective that is not useful for science or public health purposes. There is no better example than aggression as a symptom needing treatment rather than incarceration and the need to identify that symptom as early as possible.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

The responses to my post are instructive and I thought required a longer response than the brief back and forth on another blog. The arguments against me are basically:

1. You not only can't prevent violence but you are arrogant for suggesting it.

2. You really aren't interested in violence prevention but you are a cog machine of the police state and inpatient care is basically an extension of that.

3. You can treat aggressive people in an inpatient setting basically by oversedating them.

4. People who are mentally ill who have problems with violence and aggression aren't stigmatized any more than people with mental illness who are not aggressive.

These are all common arguments that I will discuss in some detail, but there is also an overarching dynamic and that is basically that psychiatrists are arrogant, inept, unskilled, add very little to the solution of this problem and should just keep quiet. All part of the zeitgeist that people get well in spite of psychiatrists not because of psychiatrists. Nobody would suggest that a Cardiologist with 25 years experience in treating acute cardiac conditions should not be involved in discussing public health measures to prevent acute cardiac disorders. Don't tell anyone that you are having chest pain? Don't call 911? Those are equivalent arguments. We are left with the curious situation where the psychiatrist is held to same medical level of accountability as other physicians but his/her opinion is not wanted. Instead we can listen to Presidential candidates and the talking heads all day long who have no training, no experience, no ideas, and they all say the same thing: "Nothing can be done."

It is also very interesting that nobody wants to address the H-bomb - my suggestion that there should be direct discussion of homicidal ideation. Homicidal ideation and behavior can be a symptom. There should be public education about this. Why no discussion? Fear of contagion? Where does my suggestion come from? Is anyone interested? I guess not. It is far easier to continue saying that nothing can be done. The media can talk about sexual behavior all day long. They can in some circumstances talk about suicide. But there is no discussion of violence and aggression other than to talk about what happened and who is to blame. That is exactly the wrong discussion when aggression is a symptom related to mental illness.

So what about the level of aggression that psychiatrists typically contain and what is the evidence that they may be successful. Any acute care psychiatric unit that sees patients who are taken involuntarily to an emergency department sees very high levels of aggression. That includes, threats, assaults, violent confrontations with the police, and actual homicide. The causes of this behavior are generally reversible because they are typically treatable mental illnesses or drug addiction or intoxication states. The news media likes to use the word "antisocial personality" as a cause and it can be, but people with that problem are typically not taken to a hospital. The police recognize their behavior as more goal oriented and they do not have signs and symptoms of mental illness. Once the psychiatric cause of the aggression is treated the threat of aggression is significantly diminished if not resolved.

In many cases people with severe psychiatric illnesses are treated on an involuntary basis. They are acutely symptomatic and do not recognize that their judgment is impaired. That places them at risk for ongoing aggression or self injury. Every state has a legal procedure for involuntary treatment based on that principle. The idea that involuntary treatment is necessary to preserve life has been established for a long time. Civil commitment and guardianship proceedings are recognition that treatment and in some cases emergency placement can be life saving solutions.

The environment required to contain and treat these problems is critical. It takes a cohesive treatment team that understands that the aggressive behavior that they are seeing is a symptom of mental illness. The meaning is much different than dealing with directed aggression by people with antisocial personalities who are intending to harm or intimidate for their own personal gain. That understanding is critical for every verbal and nonverbal interaction with aggressive patients. Aggression cannot be contained if the hospital is run by administrators who are not aware of the cohesion necessary to run these units and who do not depend on staff who have special knowledge in treating aggression. All of the staff working on these units have to be confident in their approach to aggression and comfortable being in these settings all day long.

Medication is frequently misunderstood in inpatient settings. In 25 years of practice it is still very common to hear that medication turns people into "zombies". Comments like: "I don't want to be turned into a zombie" or "You have turned everyone into zombies" are common. I remember the last comment very well because it was made by an observer who was looking at people who were not taking any medication. In fact, medication is used to treat acute symptoms and in this particular case symptoms that increase the risk of aggression. The medications typically used are not sedating. They cannot be because frequent discussions need to occur with the patient and a plan needs to be developed to reduce the risk of aggression in the future. An approach developed by Kroll and MacKenzie many years ago is still a good blueprint for the problem.

There is no group of people stigmatized more than those with mental illness and aggression. It is a Hollywood stereotype but I am not going to mention the movies. This group is also disenfranchised by advocates who are concerned that any focus on this problem will add stigma to the majority of people with mental illness who are not aggressive or violent. There are some organizations with an interest in preventing violence and aggression, but they are rare.

At some point in future generations there may be a more enlightened approach to the primitive thoughts about human consciousness, mental illness and aggression. For now the collective consciousness seems to be operating from a perspective that is not useful for science or public health purposes. There is no better example than aggression as a symptom needing treatment rather than incarceration and the need to identify that symptom as early as possible.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

Monday, July 30, 2012

PROP Petitions the FDA on Opiates

Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing (PROP) has petitioned the FDA to modify the warnings about opioids. They cite the well known dimensions of the current epidemic including a four fold increase in opioid prescribing and a four fold increase in opioid related overdose deaths. They also cite numerous references about the real risks of prescribing opioids for chronic non cancer pain with very little guidance.

PROP highlights a big problem in medical research and associated public policy and that is the biasing influence of the pharmaceutical industry and a few people at the top. The Institute of Medicine was instrumental in highlighting the issue of chronic pain and framing it as a discrete disease. Although not mentioned specifically by PROP, the Joint Commission (then known as JCAHO) promoted pain recognition and treatment in the year 2000. As this excerpt shows that initiative did not go well.

"In 2001, the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) introduced the concept that pain was the “fifth vital sign,” in an effort to increase the awareness of pain in the hospitalized patient, and by design, improve the treatment of that pain. Unfortunately, the current emphasis on pain assessment as the fifth vital sign has resulted in the potential overmedication of a group of patients (139)" (see ref 1).

Without going into detail at this time, I think that are recurrent patterns of federal and state governments, the managed care industry, and the pharmaceutical industry and their affiliated organisations driving practice patterns and treatment guidelines based on very little evidence. That culminates in broad initiatives like the PPACA that are widely hyped as advances in medical treatment, but they are basically an experiment in medicine founded on business and financial rather than scientific principles. There may be no better example than the practice of prescribing opioids for chronic non cancer pain.

Another contrast for this essay is the comparison with what has been years of psychiatric criticism based on the same principles. The basic argument from the media, antipsychiatrists, generic psychiatric critics, and grandstanding politicians has been that the pharmaceutical industry has been able to financially influence psychiatrists to prescribe drugs that are at the best worthless or at the worst downright dangerous (their characterizations). That despite the fact that black box warnings on psychiatric medication may be held to a much higher standard than other medication even if they target the same level of morbidity and mortality. After all, there is no known psychiatric medication that is mass prescribed and has resulted in overdose deaths at the rate that people are currently dying from prescribed opioids.

Just a few weeks ago, the FDA posted a number of initiatives on their web site focused on the prescription of extended release opioids. My read through the most detailed document shows that it does not touch on the principles outlined by PROP. The idea that this is strictly a matter of educating physicians is an oversimplification. This is a matter of creating initiatives that governments and sanctioning bodies insist that physicians follow and then coming up with other rules when the original ideas fail.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

PROP highlights a big problem in medical research and associated public policy and that is the biasing influence of the pharmaceutical industry and a few people at the top. The Institute of Medicine was instrumental in highlighting the issue of chronic pain and framing it as a discrete disease. Although not mentioned specifically by PROP, the Joint Commission (then known as JCAHO) promoted pain recognition and treatment in the year 2000. As this excerpt shows that initiative did not go well.

"In 2001, the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) introduced the concept that pain was the “fifth vital sign,” in an effort to increase the awareness of pain in the hospitalized patient, and by design, improve the treatment of that pain. Unfortunately, the current emphasis on pain assessment as the fifth vital sign has resulted in the potential overmedication of a group of patients (139)" (see ref 1).

Without going into detail at this time, I think that are recurrent patterns of federal and state governments, the managed care industry, and the pharmaceutical industry and their affiliated organisations driving practice patterns and treatment guidelines based on very little evidence. That culminates in broad initiatives like the PPACA that are widely hyped as advances in medical treatment, but they are basically an experiment in medicine founded on business and financial rather than scientific principles. There may be no better example than the practice of prescribing opioids for chronic non cancer pain.

Another contrast for this essay is the comparison with what has been years of psychiatric criticism based on the same principles. The basic argument from the media, antipsychiatrists, generic psychiatric critics, and grandstanding politicians has been that the pharmaceutical industry has been able to financially influence psychiatrists to prescribe drugs that are at the best worthless or at the worst downright dangerous (their characterizations). That despite the fact that black box warnings on psychiatric medication may be held to a much higher standard than other medication even if they target the same level of morbidity and mortality. After all, there is no known psychiatric medication that is mass prescribed and has resulted in overdose deaths at the rate that people are currently dying from prescribed opioids.

Just a few weeks ago, the FDA posted a number of initiatives on their web site focused on the prescription of extended release opioids. My read through the most detailed document shows that it does not touch on the principles outlined by PROP. The idea that this is strictly a matter of educating physicians is an oversimplification. This is a matter of creating initiatives that governments and sanctioning bodies insist that physicians follow and then coming up with other rules when the original ideas fail.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

1. Trescot AM, Helm S, Hansen H, Benyamin R, Glaser SE, Adlaka R, Patel S, Manchikanti L. Opioids in the management of chronic non-cancer pain: an update of American Society of the Interventional Pain Physicians' (ASIPP) Guidelines. Pain Physician. 2008 Mar;11(2 Suppl):S5-S62. Review. PubMed PMID: 18443640.

Monday, July 23, 2012

Politics and Prescribing: The Case of Atomoxetine

Prior authorizations for medications have been a huge waste of physician time and they are a now classic strategy used by PBMs and managed care companies to force physicians to prescribe the cheapest possible medication. The politics for the past 20 years is that all of the medications in a particular class (like all selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) are equivalent and therefore the cheapest member of that class could be substituted for any other drug. The managed care rhetoric ignores the fact that the members of that class do not necessarily have the same FDA approved indications. It also ignores basic science that clearly shows some members of the class may have unique receptor characteristics that are not shared by all the members in that class. Most of all it ignores the relationship between the physician and the patient especially when both have special knowledge about the patient's drug response and are basing their decision-making on that and not the way to optimize profits for the managed care industry.

The latest best example is atomoxetine ( brand name Strattera.). Atomoxetine is indicated by the FDA for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. It is unique in that it is not a stimulant and that it is not potentially addicting. Many people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder prefer not to take stimulants because they feel like they are medicated and it dulls their personality. In that case, they may benefit from taking atomoxetine. The problem at this time is there are no generic forms of atomoxetine in spite of the fact that there are many good reasons for taking it rather than a stimulant. As a result physicians are getting faxes from pharmacies requesting a "substitute" medication for the atomoxetine. Stimulants are clearly not a substitute. Some people respond to bupropion or venlafaxine but they are not FDA indicated medications for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Guanfacine in the extended release form is indicated for ADHD in children, but it is also not a generic and is probably at least as expensive. There is no equivalent medication that can be substituted especially after the patient has been out of the office for a week or two and a discussion of a different strategy is not possible.

I am sure that in many cases the substitutions are made and what was previously a unique decision becomes a decision that is financially favoring the managed care industry. I would like to encourage anyone in that situation to complain about this to the insurance commissioner of your state. It is one of the best current examples I can think of to demonstrate the inappropriate intrusion of managed care into the practice of medicine and psychiatry.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

The latest best example is atomoxetine ( brand name Strattera.). Atomoxetine is indicated by the FDA for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. It is unique in that it is not a stimulant and that it is not potentially addicting. Many people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder prefer not to take stimulants because they feel like they are medicated and it dulls their personality. In that case, they may benefit from taking atomoxetine. The problem at this time is there are no generic forms of atomoxetine in spite of the fact that there are many good reasons for taking it rather than a stimulant. As a result physicians are getting faxes from pharmacies requesting a "substitute" medication for the atomoxetine. Stimulants are clearly not a substitute. Some people respond to bupropion or venlafaxine but they are not FDA indicated medications for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Guanfacine in the extended release form is indicated for ADHD in children, but it is also not a generic and is probably at least as expensive. There is no equivalent medication that can be substituted especially after the patient has been out of the office for a week or two and a discussion of a different strategy is not possible.

I am sure that in many cases the substitutions are made and what was previously a unique decision becomes a decision that is financially favoring the managed care industry. I would like to encourage anyone in that situation to complain about this to the insurance commissioner of your state. It is one of the best current examples I can think of to demonstrate the inappropriate intrusion of managed care into the practice of medicine and psychiatry.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

Saturday, July 21, 2012

Colorado Mass Shooting Day 2

I have been watching the media coverage of

the mass shooting incident today - Interviews of family members,

medical personnel and officials. I saw a trauma surgeon at one

of the receiving hospitals describe the current status of patients taken to

his hospital. He described this as a "mass casualty

incident". One reporter said that people don’t want insanity to

replace evil as a focus of the prosecution.

In an interview that I think surprised the interviewer, a family member talked about the significant impact on

her family. When asked about how she would "get her head around

this" she calmly explained that there are obvious

problems when a person can acquire this amount of firearms, ammunition, and

explosives in a short period of time. She went on to add that she works

in a school and is also aware of the fact that there are many children with

psychological problems who never get adequate help. She thought a lot of

that problem was a lack of adequate financing.

I have not listened to any right wing talk radio

today, but from the other side of the aisle the New York Times headline

this morning was "Gunman Kills 12 in Colorado, Reviving Gun Debate."

Mayor Bloomberg is quoted: “Maybe it’s time that the two people who

want to be president of the United States stand up and tell us what they are

going to do about it,” Mr. Bloomberg said during his weekly radio program,

“because this is obviously a problem across the country.”

How did the Presidential candidates respond?

They both pulled down the campaign ads and apparently put the

attack ads on hold. From the President today: " And if there’s

anything to take away from this tragedy, it’s a reminder that life is

fragile. Our time here is limited and it is precious. And what

matters in the end are not the small and trivial things which often consume our

lives. It’s how we choose to treat one another, and love one

another. It’s what we do on a daily basis to give our lives meaning and

to give our lives purpose. That’s what matters. That’s why we’re

here." A similar excerpt from Mitt Romney: "There will be

justice for those responsible, but that’s another matter for another day. Today

is a moment to grieve and to remember, to reach out and to help, to appreciate

our blessings in life. Each one of us will hold our kids a little closer,

linger a bit longer with a colleague or a neighbor, reach out to a family

member or friend. We’ll all spend a little less time thinking about the worries

of our day and more time wondering about how to help those who are in need of

compassion most."

These are the messages that we usually hear from

politicians in response to mass shooting incidents. At this point these messages are necessary, but the transition from this incident is as important. After the messages of condolences, shared grief, and

imminent justice that is usually all that happens. Will either candidate

respond to Mayor Bloomberg's challenge? Based on the accumulated history

to date it is doubtful.

A larger question is whether anything can be done apart from the reduced access to firearms argument. In other words, is there an approach to directly intervene with people who develop homicidal ideation? Popular consensus says no, but I think that it is much more likely than the repeal of the Second Amendment.

A larger question is whether anything can be done apart from the reduced access to firearms argument. In other words, is there an approach to directly intervene with people who develop homicidal ideation? Popular consensus says no, but I think that it is much more likely than the repeal of the Second Amendment.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

Barack Obama. Weekly

Address: Remembering the Victims of the Aurora Colorado Shooting.

July 21, 2012.

Mitt Romney. Remarks by Mitt

Romney on the Shooting in Aurora, Colorado. NYTimes July 20,

2012.

Friday, July 20, 2012

Mass shootings - How Many Will Be Tolerated?

I have been asking myself that question repeatedly for the past several decades. I summarized the problem a couple of months ago in this blog. In the 12 hour aftermath of the incident in Aurora, Colorado I have already seen the predictable patterns. Condolences from the President and the First Lady. Right wing talk radio focused on gun rights and how the liberals will predictably want to restrict access to high capacity firearms. Those same radio personalities talking about how you can never predict when these events will happen. They just do and they cannot be prevented. One major network encouraging viewers to tune in for more details on the "Batman Massacre."

We can expect more of the same over the next days to weeks and I will not expect any new solutions. Mass shootings are devastating for the families involved. They are also significant public health problems. There is a body of knowledge out there that has not been applied to prevent these incidents and these incidents have not been systematically studied. The principles in the commentary statement listed below still apply.

It is time to stop acting like this is a problem that cannot be solved.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

A Commentary Statement submitted to the StarTribune January 18, 2011 from the Minnesota Psychiatric Society, The Barbara Schneider Foundation, and SAVE - Suicide Awareness Voices of Education

We can expect more of the same over the next days to weeks and I will not expect any new solutions. Mass shootings are devastating for the families involved. They are also significant public health problems. There is a body of knowledge out there that has not been applied to prevent these incidents and these incidents have not been systematically studied. The principles in the commentary statement listed below still apply.

It is time to stop acting like this is a problem that cannot be solved.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

A Commentary Statement submitted to the StarTribune January 18, 2011 from the Minnesota Psychiatric Society, The Barbara Schneider Foundation, and SAVE - Suicide Awareness Voices of Education

Wednesday, July 18, 2012

On the Validity of Pseudopatients

Every

now and again the detractors and critics of psychiatry like to march out the

results of an old study as "proof" of the lack of validity of

psychiatric diagnoses. In that study, 8 pseudopatients feigned

mental illness to gain admission to 12 different psychiatric hospitals.

The conclusion of the study author was widely seen as having significant

impact on the profession, but that conclusion seems to have been largely

retrospective. I started my training about a decade later and there were

no residuals at that time. I learned about the study

largely through the work of antipsychiatrists and psychiatric

critics.

Several

obvious questions are never asked or answered by the promoters of this test as

an adequate paradigm. The first and most obvious one is why this has not

been done in other fields of medicine. It would certainly be easy to do.

I could easily walk into any emergency department in the US and get

admitted to a Medicine or Surgical service with a faked diagnosis. I know

this for a fact, because one of the roles of consulting psychiatrists to

Medicine and Surgery services is to confront the people who have faked illness

in order to be admitted. Kety (9) uses a more blunt example in response to

the original pseudopatient experiment (1):

"If I were to drink a quart of blood and,

concealing what I had done, come to the

emergency room of any hospital vomiting blood, the behavior of the staff

would be quite predictable. If they labeled and treated me as having

a bleeding peptic ulcer, I doubt that I could argue convincingly that

medical science does not know how to diagnose that condition. "(9)

I also

know that this happens because of the current epidemic of prescription opiate abuse and the problem of drug seeking

and being successful at it. An estimated 39% of diverted drugs (7) come from "doctor shopping." By definition

that involves presenting yourself to a physician in a way

to get additional medications. In the case

of prescription opioids that usually means either faking a pain

disorder or misrepresenting pain severity. So it is well established that

medical and surgical illness well outside of the purview of psychiatry can be

faked. And yet to my knowledge, there is hardly any research on this

topic and nobody is suggesting that medical diagnoses don't exist because they

can be faked. Does that mean the researchers consider the time of these

other doctors too valuable to waste? More likely it did not fit a preset

research agenda.

The

second obvious question has to do with conflict of

interest. It is currently in vogue to suggest that psychiatrists

are swayed in their prescribing practices by incentives ranging from

a free pen to a free meal. Compensation as a company employee or to give

lectures is also thought of as a compromising incentive. The free pen/free meal

incentive is pretty much historical at this time. What about

intentionally misrepresenting yourself? What is the conflict of

interest involved at that level and how neutral can you stay when you are