Showing posts with label psychiatry. Show all posts

Showing posts with label psychiatry. Show all posts

Wednesday, April 13, 2016

Euthanasia And Other Ethical Arguments Applied To Psychiatric Patients

An article entitled Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide of Patients With Psychiatric Disorders in the Netherlands 2011-2014 caught my eye in this month's JAMA Psychiatry (1). It wasn't that long ago that I recall being in the midst of a rather intense argument in a staff meeting about euthanasia in the broadest of terms. Like many heated political arguments (I consider a lot of what goes on under the heading of ethics to be little more than politics) this one degenerated to personal terms. The pro-euthanasia proponent ended the argument with: "Well if I am dying of terminal cancer and I want to end it, there is no one who is going to tell me that I can't do it. Not you or anyone else." In the dead silence that followed nobody brought up the obvious point that is the state of affairs currently. Euthanasia proponents have always made that argument when in fact what they really want is to recruit physicians to provide them with euthanasia. That is hardly the same thing as actively stopping them. I would make the secondary argument that nobody really needs to be actively recruited these days. I can't remember the last legal battle about whether a physician providing hospice care ordered too many opioids and benzodiazepines for a suffering terminally ill patient. If I had to guess, the last time I saw that question raised in a court in the Midwest was about 20 years ago.

The concept of euthanasia in patients with psychiatric disorders is an even more complicated process. Psychiatric disorders per se are not terminal illnesses, there is no protracted phase of increasing suffering and futile live saving measures with a fairly predictable death. Death primarily due to psychiatric disorders occurs as a result of suicide, risk taking, comorbid medical illnesses, and severe disruptions in self care and homeostasis due to acute disorders like catatonia. These are all relatively acute processes. That does not mean that there are no people with chronic mood disorders, personality disorders, and psychoses. Is the suffering in these situations acute and severe enough that euthanasia should be considered and if so, do any standards apply?

The authors of the Dutch study set out to study the characteristics of psychiatric patients receiving euthanasia or assisted suicide (EAS) in Belgium and the Netherlands. The case studies of 66 cases were reviewed in the database of the Dutch regional euthanasia review committees. There were 46 women and 20 men. A little over half (52%) had made previous suicide attempts. 80% had been hospitalized in psychiatric units. Most of the patients were aged 50-70 but 1/3 were older than 70. Most (36) had depression and 8 of those patients had psychotic features. The patients were described as chronically symptomatic and 26 patients had electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Two had deep brain stimulation - one for obsessive compulsive disorder and one for depression. There was significant medical comorbidity. The authors comment that there was very little social history to the point that they could not reconstruct the persons current living situation from what was abstracted. Some of the reports contained fairly subjective data - as an example: "The patient was an utterly lonely man whose life had been a failure." There was extensive treatment but also treatment refusal in 56%.

Twenty-one patients had been refused EAS at some point and in 3 of these cases the original physician changed their mind and performed EAS. In the other 18 patients, the physician performing the EAS was new to the patient. In 14 of those cases that physician was affiliated with a mobile euthanasia practice called the End-of-Life Clinic. In 27 cases a psychiatrist did EAS and the rest were general practitioners. Physicians disagreed in about 24% of the cases and EAS proceeded despite the disagreement. In 8 cases the psychiatric consultant did not think that due care criteria specifying "no reasonable alternative" had been met. The Euthanasia Review Committee (ERC) found that due care criteria were met in all psychiatric cases referred except for one. In another case the ERC was described as being critical but in the end agreed with the euthanasia decision. It was a case of a man who broke his leg in a suicide attempt and then refused all treatment and requested EAS.

The authors come to several conclusions. The first involves the issue that in this study the ratio of women to men was 2.3 to 1 and that is the opposite of what is expected with suicide. They suggest that the availability of EAS may make the desire to die "more effective" for women. Although the overall psychiatric sample was younger than the non-psychiatric EAS cases, they argue that the fact that a significant portion have significant comorbidities and this may indicate that Dutch physicians tend to self regulate EAS to a specific patient profile. They point out that more judgment is required in psychiatric cases than in the cases involving terminal physical illness - 83% of which involved a malignancy. They note that decision-making capacity can be affected by neuropsychiatric illness and that medical futility is difficult to determine especially when care is refused. There were no official EAS psychiatric consultants involved in 41% of the cases. In 11% of cases there was no psychiatric involvement at all. Their overarching observation was that EAS for psychiatric illnesses involved making decisions about complex disorders and considerable judgment needed to be exercised. They suggested that the decision about EAS required "considerable physician judgment" and that regional committees overseeing euthanasia deferred to the opinion of the treating physician when consultants disagreed.

I have never seen it discussed but conflict of interest issues are prominent in any decisions about the autonomy of people who are designated psychiatric patients. At the first level, there is the wording of the policy or statute. There are criteria that are thought to be very objective that are used to decide if a person should be subject to civil commitment, guardianship, conservatorship, or any of the laws involving competency to proceed to trial, cooperate with one's defense attorney, or a mental illness or defect defense. In all cases, the wording of each state's statute would seem to determine an obvious standard. Those standards are routinely compromised in practice by any number of political considerations. In the case of not guilty by reason of mental illness, the compromise occurs any time there are high profile cases that involve heinous crimes. No matter how severe the mental illness, there will be a raft of experts on either side and the verdict will almost always be guilty. At the other end of the spectrum is civil commitment. Observing any commitment court over time will generally show the oscillation between libertarian approaches to more strict standards where need for psychiatric treatment is the more apparent standard. The libertarian approach often uses a standard of "imminent dangerousness" as an excuse to dismiss the patient irrespective of what the statute may say. It also seems to coincide with the available resources of the responsible county. That is why in Minnesota the land of 10,000 lakes and 87 counties we say: "On any given day there are 87 interpretations of the civil commitment law." Despite that range of interpretations, it would be highly unlikely that a patient who broke his leg in a suicide attempt (a case presented in this paper) would not be a candidate for court ordered treatment rather than euthanasia. On the other hand, I do not know anything about civil commitment and forced treatment in the Netherlands.

There is no reason I can think of that a euthanasia standard can be interpreted any more logically. This Dutch study points to that. It also points to another issue that is never really discussed when it comes to psychiatric diagnosis or the ethics and laws that apply to them. The conscious state of the individual is never recognized. Brain function is parsed very crudely into separate domains of symptoms, cognitions, and decisions. The examiner or legal representative usually has some protocol by which they declare the person competent or not and the legal or ethical consequences proceed from that. There may be a discussion of personality that is also based on this parsing process. Very occasionally there is a discussion of the person's baseline, but that is about it. That is a serious problem for any student of human consciousness. Let me explain why. I think that it is a universal human experience to experience a transient (days to months) change in your conscious state that might result in you not wanting to live. The insult could be a physical or mental illness. It would seem to me that at a minimum there can be multiple conscious states operating here that look like a request for assisted suicide or euthanasia. The limits would be bounded by a completely rational decision based on medical futility and suffering on one side and an irrational decision based on the altered conscious state on the other. The only way for any examiner to make that kind of determination is to know the patient very well over time to recognize at the very least that they are not themselves. Doing an examination for the express purpose of determining if a person meets criteria for euthanasia in a short period of time is by contrast a very crude process.

There is too much variability in the patient's conscious state and how that impacts treatment and ultimately recovery to consider psychiatric disorders as a basis for a decision about euthanasia and assisted suicide.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

References:

1: Kim SH, De Vries RG, Peteet JR. Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide of Patients With Psychiatric Disorders in the Netherlands 2011 to 2014. JAMA Psychiatry.2016;73(4):362-368. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2887.

2: Appelbaum PS. Physician-Assisted Death for Patients With Mental Disorders—Reasons for Concern. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(4):325-326. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2890.

Supplementary 1: I intentionally wrote the above post without reading the accompanying commentary by Paul S. Appelbaum, MD. Dr. Appelbaum is an expert in forensic psychiatry and has written extensively on ethical issues in psychiatry. Dr. Appelbaum's essay provides some additional facts, but his areas of concern do not touch on my focus on the conscious state of the individual.

Sunday, May 31, 2015

The NIMH Director and the RDoC - The Politics and The Science

|

from: Insel TR, Cuthbert BN. Medicine. Brain disorders? Precisely.

Science. 2015 May1;348(6234):499-500.

|

I caught this article about the RDoC criteria for classifying mental illnesses based on various non descriptive parameters and neuroscience in the journal Science a couple of weeks ago. As any reader of this blog can attest, there is no stronger advocate for the role of neuroscience in current psychiatric practice and the future of psychiatry than me. There has been media controversy on this subject and it is always difficult to determine how much real controversy exists and how much of it is just made up for the sake of media self promotion like much of the DSM-5 controversy was. Reading through the article by Thomas Insel and Bruce Cuthbert there are statements that can be taken at face value. I think these statements are consistent with the position that clinicians in general are not very scientific and are also outright clueless in some areas. This is a bias that I have certainly heard from other scientists and it does not serve the cause of science very well, especially if the goal is to advance neuroscience and bring everyone up to speed on that discipline. Dr. Insel has presented his view that all of the trainees in the clinical neurosciences of psychiatry, neurology, and neurosurgery should rotate through a year or two of a shared neuroscience. When I first heard him present it five years ago I thought it was a great idea. In the time since and especially after getting a response from him, I think it is less clear. It would be great if every department of psychiatry had neuroscientists on staff to teach neuroscience. But they don't and there is also the problem of neuroscientists being focused on research rather than teaching. On the other hand, there are plenty of bright people in those departments who know a lot about the brain. It is a question of reconciling these two points to come up with the necessary infrastructure yet in this article the authors make it seem as if large clinical problems are not addressed and that clinicians are fumbling around with very crude assessment methods.

They list three articles as examples of the RDoC. The most interesting of these articles is one from the American Journal of Psychiatry that proposes that computer abstracted data from hospital notes that is converted to RDoC criteria are better predictors of hospital length of stay (LOS) than DSM criteria. Just considering that method my first impression was that there was a lot wrong with that picture. First of all, LOS data is tremendously skewed based on non-clinical practices. All it takes is hospital case managers with some success in intimidating physicians to skew the data in favor of business rather than actual medical or psychiatric discharge decisions. Second, the quality of data from inpatient settings is incredibly bad due to the toxic combination of electronic health records and government billing and coding regulations. As a reviewer, I have seen thousands of inpatient records, some of them hundreds of pages in length and I have found EHR records are notoriously poor in information content. And finally, I thought the RDoC was a new system designed to be dependent more on neuroscience than the DSM-5? How does methodology that looks at this DSM biased, sketchy clinical data result in a RDoC diagnosis? Looking at the graphic from the Science article at the top of this post, it is pretty clear that 3 out 5 data dimensions under "Integrated Data" are basically clinical data. There is a smugness displayed in the report similar to what might be seen in a rant by an antipsychiatrist: "For now clinicians might be best advised simply to be aware of the usefulness of dimensional models to capture psychopathology." and "This result should provide some reassurance to clinicians that their notes do contain relevant detail for deriving dimensional measures of illness; like Molière’s Bourgeois Gentlemen speaking prose without knowing it, clinicians may already speak some RDoC."

Really?

The average person I see has chronic insomnia and has had possible sleep terrors and nightmares in childhood along with social phobia. At some point they developed either severe anxiety or depression, but they can't recall the sequence of events and they currently have both. They typically think that they have had "manic episodes" and may have been diagnosed with bipolar disorder even though they don't know what a manic episode is. All they know is that their symptoms have persisted usually without remission for the past 10 to 15 years. Of course that is complicated by the fact that they have been using marijuana, alcohol, and opioids in excessive amounts since then, they may not have a significant family history of psychiatric and addiction problems, and they have the expected childhood adversity and adult markers of psychological trauma and abuse. Further, I know from talking to the same people in repeated initial evaluations over the years that they don't give the same history twice and rarely remember much about their medications or psychotherapy treatment. Should I use a "placeholder diagnosis" (pejorative term from reference 4) or should I assume that I am dealing with the social phobia that the patient may have had in childhood? The idea that an RDoC diagnosis is going to give me an answer to that question any better than a DSM-5 diagnosis is pure folly if you ask me. At least until we get the promised neuroscientific markers promised by the NIMH. In fact, the description of the RDoC in these articles is reminiscent of another technology that was supposed to diagnose mental illness and that was quantitative EEG or QEEG. I know quite a lot about QEEG, because I purchased a machine in the 1980s after a promising article on the technology came out in the journal Science. I researched it using highly skilled EEG techs and an expert in neurophysiology to run the protocols, and concluded the diagnoses that came from the computerized analysis of the tracing were no better than chance in terms of what patients presented with. Like RDoC diagnoses, the computerized analysis of QEEG data was highly dependent on the input of clinical data collected by the clinician. It allowed the clinician to add and subtract clinical variables and look at how the diagnosis varied.

The staff and researchers at the NIMH need to decide if a superior and critical attitude toward physicians who use current clinical approaches and are successful with them is the best one. It should be obvious from the above analysis that many of us are not as naive or as ignorant about science as they expect. My proposed solution would be a more collaborative approach including the following:

1. Recruit and train neuroscience teachers - most of them are already out there. For example much of what I teach to trainees interested in addiction and addiction medicine is neuroscience. It is also much more realistic than waiting for every department to have access to neuroscience researchers and then expecting those researchers to teach in addition to doing research. My guess is that every Psychiatry department already has faculty that teach neuroanatomy, pharmacology, brain science and neuroscience already and that most of them are not officially scientists.

2. Make the reading list available online - the article refers to over 1,000 published articles that focus on the RDoC criteria. These should be available though the National Library of Medicine web site along with other neuroscience articles of interest to psychiatrists. An added bonus would be CME activity available for self study.

3. Post a list of neuroscience modules and build on that list - In a previous post, I posted two links to neuroscience modules through the NIMH. I would put up two lists, one containing a growing list of modules and the second with a list of the neuroscience concepts that need to be illustrated. This would be useful for psychiatrists, psychiatrists in training, and medical school professors hoping to make their basic science lectures more relevant, since many clinicians still seem to have difficulty understanding how neuroscience is important in psychiatry.

4. Better graphics - make high resolution graphs that illustrate detailed brain anatomy and basic science available online for teachers. Pulling this material together is often the most difficult part of the teaching job and it requires an intensive effort to not run afoul of copyright laws. It would be easier to recruit neuroscience teachers if there are high quality teaching materials available.

5. A neuroscience teaching blog - In addition to the NIMH staff posting the references, concepts and modules, an open teaching blog should also be available. I would encourage it to be a platform for discussing concepts and how to present them to trainees. Ideally, it would be a place for active dialogue about the concepts and teaching them.

I think that all of these measures would be helpful in building an infrastructure of neuroscience teachers, neuroscience teaching, and a mechanism for the widespread dissemination of this material in residency programs and in educational programs for practicing psychiatrists. If the RDoC is in fact worthwhile, there is plenty of brainpower outside of the NIMH to figure that out.

It is the brainpower that is currently focused on coming up with solutions and resolving problems of incredible clinical complexity. And that happens every day.

I plan to send these recommendation to Director Insel and see what he thinks.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

1: Insel TR, Cuthbert BN. Medicine. Brain disorders? Precisely. Science. 2015 May

1;348(6234):499-500. doi: 10.1126/science.aab2358. PubMed PMID: 25931539.

2: Casey BJ, Craddock N, Cuthbert BN, Hyman SE, Lee FS, Ressler KJ. DSM-5 and RDoC: progress in psychiatry research? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013 Nov;14(11):810-4. doi: 10.1038/nrn3621. Review. PubMed PMID: 24135697.

3: NIMH. Research Domain Criteria

4: McCoy TH, Castro VM, Rosenfield HR, Cagan A, Kohane IS, Perlis RH. A clinical perspective on the relevance of research domain criteria in electronic health records. Am J Psychiatry. 2015 Apr;172(4):316-20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14091177. PubMed PMID: 25827030.

2: Casey BJ, Craddock N, Cuthbert BN, Hyman SE, Lee FS, Ressler KJ. DSM-5 and RDoC: progress in psychiatry research? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013 Nov;14(11):810-4. doi: 10.1038/nrn3621. Review. PubMed PMID: 24135697.

3: NIMH. Research Domain Criteria

4: McCoy TH, Castro VM, Rosenfield HR, Cagan A, Kohane IS, Perlis RH. A clinical perspective on the relevance of research domain criteria in electronic health records. Am J Psychiatry. 2015 Apr;172(4):316-20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14091177. PubMed PMID: 25827030.

Supplementary 1:

The above figure is licensed through the American Association for the Advancement of Science - license number 3637270124183.

Wednesday, March 18, 2015

Neuroscience In Psychiatry Now - It Is A Lot Easier Than It Looks

I read the article "The Future of Psychiatry as Clinical Neuroscience. Why Not Now?" by Ross, Travis, and Arbuckle in JAMA Psychiatry and found little to disagree with. I was in one of the venues a few years ago when Thomas Insel, Director of the NIMH talked about a clinical neuroscience rotation for neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry residents to bring neuroscience to the clinical side of things. Unfortunately he was a lot less enthusiastic about it when I sent him a follow up e-mail and at that time suggested it would probably have to wait for some time in the future.

As a long time neuroscience enthusiast, I have always found the reluctance to head in this direction puzzling. On a historical basis, neuroscience has always has a prominent role in psychiatric theory. One of the arguments against neuroscience has been that there are no clinical applications. Even back in the day with Alzheimer, Nissl, Kraepelin and other German neuropsychiatrists were studying brain anatomy of patients in asylums, there were important correlations - most notably those consistent with both Alzheimer's Disease and Binswanger's Disease. About two decades later, Constantin von Economo penned his treatise Encephalitis Lethargica - Its Sequelae and Treatment and described conditions that were relevant right up to the point that I started my training in the 1980s.

Being a practicing psychiatrist with an interest in neuroscience presents a variety of CME events ranging from behavioral neurology and developmental pediatric conferences in Boston to the annual Movement Disorders conference in Aspen. There were the occasional very unique courses, like the brain dissection course run by the late Lennart Heimer, MD and a faculty of outstanding neuroanatomists. But most of the neuroscience in psychiatry is typically packed into a course that focuses on the specialized diagnosis and treatment of specific disorders. A good example would be the American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry (AAGP) courses that would include a detailed discussion of Alzheimer's pathology and vascular dementia and how they might not be that disparate at the microscopic level (that was also an ongoing debate in the movement disorder conferences). In an AAGP event there would be 1 lecture out of 7 for that day devoted to neuroscience. On the teaching level, neuroscience has always been there in the form of neurotransmitters, localization of cognitive and neuropsychiatric disorders associated with various brain lesion and insults, cell signaling, and plasticity. In the past 20 years there has been an unprecedented integration of neurotransmitters and specific brain structures as seen in this diagram of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex.

I have been fantasizing about a foundation and several years ago came up with the idea that it should fund neuroscience education in psychiatry. This would be my preliminary plan:

1. Contract with the top neuroscientists in psychiatry to come up with the syllabus.

From the reviews in review edition of Academic Psychiatry (reference 4) there are already residency training programs that have come up with a systematic approach to this training. There should be a place for all programs to post what neuroscientists and researchers consider the top areas for focus. From the reviews mentioned in the above narrative it is very likely that there are fairly complete syllabi at this point but looking at the reviews in Academic Psychiatry they seem to be fairly disparate in terms of what faculty see as the most relevant. The vignettes prepared by the NIMH (reference 2 and 3) are illustrative of what is possible. If I was designing a curriculum, I would want every possible concept that could be illustrated in these vignettes and build the course work around that.

2. Develop neuroscience teaching as a specialty.

I doubt that there are enough neuroscientists around to teach the subject to psychiatry residents. A group dedicated to teaching neuroscience and neuroscientific formulations would be a logical approach. There are currently plenty of nonscientist faculty with an interest and more than a passing knowledge of neuroscience.

3. Develop a repository of graphics and teaching materials.

There is no area of psychiatry that could benefit more from high quality graphics for teaching. Current faculty engaged in teaching need to run a gauntlet of copyright related issues ranging from implicit copyright permission (yes you can use for teaching without going through Copyright Clearance Center) to repetitive licensing fees that are difficult to track. All of those problems are from publishers controlling these rights and in some cases charging unrealistic amounts for reuse of some of these works. Open access work is a potential solution but it is doubtful that enough graphics currently exist to illustrate key neuroscience principles. A coalition of residency programs can potentially contract for the production of custom figures for a central repository that could be used in residency programs across the country. There is already a precedent for this process with the psychopharmacology course available to residency programs from the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology (ASCP) who produce a large number of PowerPoints that are available to residency programs for a very reasonable fee.

5. Don't forget about addiction science.

The field of addiction has contributed immensely to understanding how the brain functions. In many cases psychiatry residents have minimal exposure to the treatment of substance use disorders and the associated syndromes and that could potentially strengthen both those areas in any residency program.

6. Hold annual review courses.

The field as it applies to psychiatry contains neuroscience spread across gatherings for psychopharmacology, geriatric psychiatry, general psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, sleep medicine, addiction medicine and behavioral neurology. There should be meetings across the country that focus on the necessary neuroscience and formulations presented by the top experts in the world with that focus.

7. Suggested readings.

I try to keep up with Nature, Science, and Neuron and the Science Signaling series as a cost effective approach to learning new developments about neuroscience and whatever open access journals that seem to have the best content. There are top journals that are too expensive or require memberships where the threshold is set for researchers and not teachers. A good general approach to how to approach the literature would be very useful for most of the teachers and some of the expensive journals might offer packages for teachers rather than researchers. I can recall that when I interviewed for residency positions and asked about department recommended reading lists there was only one department who provided one in those days. I will let readers guess about which department that was.

8. Reviewing imaging studies and teaching files.

Some of the best neuroanatomical preparation and training in my career came from reviewing imaging studies with radiologists, neuroradiologists, neurologists and neurosurgeons. Current electronic medical records make viewing imaging studies easier than at any time in the past. There is no better learning procedure than to organize findings, order the test, and confirm the problem. That is possible currently if you treat a lot of patients with apparent lesions on imaging but functional imaging is becoming more available it has the potential to revolutionize psychiatric practice. As an example, listen to the story called How To Cure What Ails You and an enthusiastic Eric Kandel talk about the importance of the anatomical substrate (reference 5) in psychiatric disorders.

These are some of my current ideas. I look forward to the day that a neuroscientific formulation about what might be relevant is contained in the same paragraph that includes social and psychological formulations. It will also put psychiatrists back where most of us belong - seeing people with the most difficult problems rather giving out advice on how to prescribe antidepressants.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

References:

1: Ross DA, Travis MJ, Arbuckle MR. The Future of Psychiatry as ClinicalNeuroscience: Why Not Now? JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 Mar 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3199. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 25760896

2: National Institute of Mental Health neuroscience and psychiatry modules. 2012a. Available at http://www.nimh.nih.gov/neuroscience-and-psychiatry-module/index.html. Accessed on March 16, 2015.

3: National Institute of Mental Health neuroscience and psychiatry modules: 2012b. Available at http://www.nimh.nih.gov/neuroscience-and-psychiatry-module2/index.html. Accessed on March 16, 2015.

4: Coverdale J, Balon R, Beresin EV, Louie AK, Tait GR, Goldsmith M, Roberts LW. Teaching clinical neuroscience to psychiatry residents: model curricula. Acad Psychiatry. 2014 Apr;38(2):111-5. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0045-7. Epub 2014 Feb 4. Review. PubMed PMID: 24493360.

4: Coverdale J, Balon R, Beresin EV, Louie AK, Tait GR, Goldsmith M, Roberts LW. Teaching clinical neuroscience to psychiatry residents: model curricula. Acad Psychiatry. 2014 Apr;38(2):111-5. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0045-7. Epub 2014 Feb 4. Review. PubMed PMID: 24493360.

5: How To Cure What Ails You. Radiolab Accessed on March 17, 2015.

Supplementary:

The header to this article is all of my copies of The Biochemical Basis of Neuropharmacology and the book I consider to be its successor Introduction to Neuropsychopharmacology. New editions of BBN came out in 1970, 1974, 1978, 1982, 1986, 1991, 1996, and 2003. The copy with the white cover in the middle (a little faded) was the first copy I owned. In those days I wrote the year I purchased books in the front jacket and that year was 1984. This book with its elegant little drawings and low purchase price served as an introductory neuroscience text to many classes of psychiatry residents.

Supplementary:

The header to this article is all of my copies of The Biochemical Basis of Neuropharmacology and the book I consider to be its successor Introduction to Neuropsychopharmacology. New editions of BBN came out in 1970, 1974, 1978, 1982, 1986, 1991, 1996, and 2003. The copy with the white cover in the middle (a little faded) was the first copy I owned. In those days I wrote the year I purchased books in the front jacket and that year was 1984. This book with its elegant little drawings and low purchase price served as an introductory neuroscience text to many classes of psychiatry residents.

Saturday, March 7, 2015

The Chai Man

Back in the 1970s I was in the US Peace Corps in Kenya East Africa. I worked in an all boys school as a chemistry teacher. The school was about 100 miles north of Nairobi on a high plateau next to Mt. Kenya. On the weekends my fellow volunteers and I would drive over to the closest town for a Coke and an inexpensive snack at the White Rhino Hotel. In those days a Coke or a bottle of beer would cost about a Kenyan Shilling (KES) and a meat pie or a samosa would cost about a Shilling and a half. One Shilling was about 14 cents American. Outside the hotel was an apparently homeless man. He would beg for money often by creating disturbances. He would obstruct people in the street going to and from the hotel. He would shout out the word "Chai, Chai..." repeatedly while spitting down the front of his shirt. "Chai" is the Kiswahili word for tea. He would appear agitated and tearful at times. He was not tolerated very well by hotel security or the local people - people who could speak fluent Kiswahili and the local Kikuyu language. Some of them would become physically aggressive toward him and cause him to run down the street. At other times he would show up with a can of dirty water and try to clean auto windshields by wetting down a newspaper and wiping the water all over. These attempts were always unsolicited and the drivers would become enraged because their windshields were always less clean than when he started. We eventually referred to him as the Chai Man because nobody ever knew his name. The Chai man clearly struggled, alienated practically every person I ever watched him interact with, and he got minimal assistance from anyone. At the time he reminded me of homeless men I would see in my local public library. It was the only they place they could go in a small town to get a break from the weather. They would occasionally ask for money, but for the most part avoided people. When you are down and out and mentally ill, most people seem to know better than to ask.

By the time my fellow teachers and I made it to our placement north of Nairobi we had contact with hundreds if not thousands of people living on the street as beggars. Many had physical deformities to the point that they were unable to walk. Coming into town from the airport was enough contact to convince the most altruistic Peace Corps volunteer (PCV) that they personally did not have nearly enough resources to address the problem. PCVs had to learn to not look at the people begging on the street and walk quickly by or risk people coming out and grabbing their leg or arm until they were given money. Like the US, only certain streets and areas allowed for the aggregation of these homeless beggars. PCVs were not rich by any means but when we got to our eventual destinations, they were usually places where there were no homeless people in sight. We were rather scruffy ourselves but we could sit in classy places like the New Stanley Hotel and sip on a Coke.

I thought of the Chai Man last night as I listed to a program on "The World" on MPR about a mental health initiative in Kenya (reference 1). The focus of the program was a young woman Sitawa Wafula started mental health crisis intervention service on her own. It is a formidable problem. The program describes how children and adults are "locked up" by their families and may not see the light of day. Neighbors often do not know that a mentally ill brother or sister exists. This is reminiscent of Shorter's description of the problem of psychosis in Europe and how it was handled in the early 20th century. It also happened in my own family in the early 1950s. In Kenya, there are currently 79 psychiatrists or one for very 500,000 people. Ms. Wafula gets a number of calls to her crisis intervention service and says that if the problem involves suicidal thinking many people with that problem have had two previous suicide attempts. The World Health Organization puts Kenya in the top quartile of suicide rates in all countries worldwide.

I was picked up by a Kenyan physician once when I was hitchhiking back to Nairobi one day. I asked him what was available in terms of psychiatric services at the time. He said there was only one hospital and that the basic medication being prescribed by physicians was chlorpromazine. At that time, the chlorpromazine generation of antipsychotics were the only ones available and antidepressants were more difficult to prescribe. Medical care in general was difficult to access. I would typically get scabies at least one a month. When I was initially infected I made the mistake of going to a local clinic and standing in line in the hot sun. I was about number 300 in the line and it moved about 4 or 5 spaces every hour. I realized that I could hitchhike 100 miles to Nairobi and back and pick up the appropriate treatment from the Peace Corps physician in less time than it took to go to the local clinic. Eventually I just picked up a large bottle scabicide and applied it whenever I got infected. At the time Kenya also had one of the fastest growing populations making it more difficult to provide medical and psychiatric care.

About 8 years after I left Africa, I was sitting in a seminar full of fellow psychiatry residents at the University of Wisconsin. The topic of the day was whether or not the prognosis of schizophrenia was better in what was then called the "the third world" based on some outcome studies available at the time. Our job was to critique the literature and it was apparent that there were technical differences in studies and in many areas the follow up and methodology was different. At one point I suggested that exposure to antipsychotic medications may lead to negative outcomes and that raised an eyebrow or two. I also pointed out that that at least half of the people I was treating had significant alcohol and drug problems and were not interested in quitting. I doubted that many of the people in these studies had widespread access to street drugs that were known to precipitate psychotic states. I remembered the Chai Man very well, but knew better than to introduce my anecdotal experience from Kenya. That axiom about better prognosis in the developing world has since been re-examined (reference 2) and there are clearly more problems with that theory than originally thought. Like many areas in psychosocial research it may depend more on your political biases before you read the research. The Scandinavian research on brief psychosis and brief reactive psychosis from about the same time frame certainly suggested similar rates of spontaneous recovery.

These experiences make me smile at couple of levels. Any time someone "confronts" me with the evidence of prognosis in schizophrenia and the World Health Organization (WHO) studies, I can point out I had a better and more thorough discussion about it with fellow psychiatrists in 1986. I have also lived in a developing country and saw how people with presumptive mental illnesses were treated. I have applied that experience and knowledge to clinical practice in this country.

There is the curious parallel of access to psychiatrists in both countries. How do the citizens who need them the most get access to them? The public radio story suggests that only people with resources (I take that to mean money) can get access to the limited number of psychiatrists in Kenya. This country is headed in the same direction largely because rational psychiatrists do not want to be ordered around by insurance companies. In the case of access for the severely disabled, individual states have different plans but the overall plan has been to ration access and incarcerate rather than hospitalize people with mental illnesses. In the US, there is generally an order of magnitude greater number of psychiatrists, but that does not translate to more access. I have talked to too many people who stop seeing a psychiatrist when their insurance stops. The insurance industry, state governments, and the federal government all have an interest in restricting access to psychiatrists. If people only see psychiatrists if they have poor insurance coverage and psychiatrists are fleeing insurance - this is a chronic problem that will only get worse.

In the meantime, I hope that Ms. Wafula continues to be successful in her crisis intervention program and raising awareness that severe mental illness is a public health problem that needs to be addressed. Families should have more resources and more help. The WHO program to raise awareness about suicide also seems like a good idea.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

References:

1. Emily Johnson. Fighting the 'funk:' How one Kenyan battles her mental health problems by helping others. PRI The World. March 3, 2015.

2. Cohen A, Patel V, Thara R, Gureje O. Questioning an axiom: better prognosis for schizophrenia in the developing world? Schizophr Bull. 2008 Mar;34(2):229-44. Epub 2007 Sep 28. Review. PubMed PMID: 17905787

Supplementary 1: The map graphic is from the CIA Factbook in the public domain.

Supplementary 2: WHO Infographic on Suicide.

Supplementary 3: I mention the New Stanley Hotel in this post, but sometime after I was there it was blown up by terrorists. The replacement versions (at least according to Google) continue to be threatened by terrorists, who apparently want to target the tourist business in Kenya.

Sunday, September 28, 2014

Neanderthals - Real Human Differences and Stereotypes

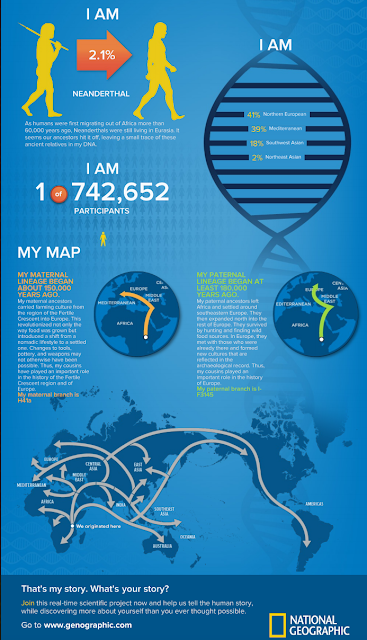

That's right - I am 2.1% Neanderthal. There have been some fascinating developments in human paleogenetics in the past decade including the characterization of genomes other hominins including the Neanderthals and the Denisovans from old remains. It casts a different light on some of the stories based on stereotypes from the past. For example, the common view of Neanderthals were that they were strong, but not very intelligent or sophisticated beings. As as result Homo sapiens could easily outcompete these brutes and as a result modern day man is the only surviving species. It was quite a surprise to learn that after the Neanderthal genome had been characterized portions of it could be identified in the modern human genome and that ancient DNA may have a role in the HLA (human leukocyte antigen) genes that play a central role in immunity. There is the related question about whether incorporating the DNA of a new species could lead to certain autoimmune problems. That fact compounded my interest in this area that was originally piqued by the first NatGeo Genographics project. That project gave confirmation and graphics to the fact that at some point or another about 60-70,000 years ago, our ancestors walked out of the Rift Valley in East Africa and began their migrations around the globe. Some of those folks migrating north through Europe encountered Neanderthals and Denisovans along the way. Contrary to the conventional story that humans "outcompeted" them, they mated and produced offspring.

A quick review on relevant taxonomy. From zoology, the naming convention is Genus and species. Modern humans are Homo sapiens. Considering this convention there were about 16 different species of the genus Homo and apart from Homo sapiens all of the others are extinct. That includes Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) and Denisovans. In historical terms, at one time or another there was more than one Homo genus walking the earth. Looking at a graphic from the Smithsonian suggests that Homo sapiens, Homo floresiensis, Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis), and Denisovans were all walking the Earth sometime in the time zone about 20-30,000 years ago. Genetic technology has revolutionized this area of morphology based research. There is a lot of speculation but no good conclusions about why Homo sapiens is the only surviving species.

I don't know if they still teach this in Medical School but in all of my major rotations I was taught to describe the patient in the first sentence by age, sex, and ethnicity based on outward appearance. There were various rationales provided for that opening sentence but even in medical school (now a long time ago) they did not make a lot of sense to me. Of course there were cultural and political influences on these descriptions. The "38 year old black male..." became the "38 year old African-American male..." at some point and back again depending on the politically correct term of the time. It was all very unscientific, but many physicians seemed to think that it was a more medically precise way to talk about the patient and condense relevant information about that patient. I did not have to consider anything beyond "male-female" versus "man-woman" to decide that my notes would never start with these words. The only facts that I capture in my opening lines is the actual age of the patient and whether they are a man or a woman. Male and female are non-specific terms and don't reflect the fact that I am talking about a human being. You could say that this is an old convention, but I still see it as present in most medical records that I review. In fact, it has stretched so that in some cases the characterization of white people has progressed from White to Caucasian to European, even though the person in question and their family has not set foot in Europe in over three or four generations. I guess I also missed the politically correct convention that white folks were now "European Americans" and yet I have seen that frequently in medical records.

I read a paper in Science about 20 years ago that there were no genetically significant differences based on race or skin color. It what seemed like a surprisingly simple statement, the authors pointed out that all humans are much more genetically related to one another than to non-human primates. Genetic differences based on skin color and facial features were trivial to non-existent. If you look at it that way that opening line: "24 year old Hispanic female..." becomes little more than an unscientific stereotype. Why include it in the medical record? Some might say that it provides the opportunity for the delivery of culturally appropriate health care. If that is the case, I would suggest including a more accurate description of the patients culture (as described by them) rather than presuming their culture based on their physical appearance or a check off on a standard intake form. Scientific rather than stereotyped descriptions of people should be the standard.

A related issue is how much people actually know about themselves and their family of origin. On the average, most of the people I talk with about their family histories know the high points for about 3 generations. Physicians are typically focused on heritable diseases but most third and fourth generation Americans in this country don't know much about how their families migrated to the US and where they were migrating before that. The first humans migrated out of the Rift Valley in East Africa about 70,000 years ago. That is 2800 generations ago, maybe more if we need to correct for the short longevity of prehistoric man. The fact that we are all Africans to start with and that so-called racial differences were a byproduct of the migration is a huge fact that nobody talks about. It has far reaching implications and it is why I like to talk about it.

The other issue is what happened to the Neanderthals? The story used to be that the Neanderthals were typical cave men. They were squat muscular, and not very bright. Their fate was considered to be extinction because they were outclassed and outcompeted by Homo sapiens. Paleogenetics has led to those assumptions being challenged. An excellent Nova special called Decoding Neanderthals captures some of the surprise and excitement of some of the first scientists who discovered Neanderthal DNA in the human genome. That program also looks at how inferences can be made about prehistoric beings based on both the archaeological evidence and the genetic evidence. In the case of archeology, the complexity of Neanderthal flint tool technology was investigated. They had a method of making flint tools with a broad sharp edge that could be resharpened. It was termed Levallois technology and the complexity suggests a higher level of intelligence than is commonly assumed. The second Neanderthal technology that was discovered was using a type of pitch on some of their implements. To manufacture this early epoxy required mastery of a thermal process again suggesting advanced intelligence. The final piece of evidence is the presence of the FOXP2 gene. This gene is responsible for speech and language in humans. There are FOXP2 variants, but when the Neanderthal DNA was decoded, it contained a copy of the FOXP2 gene identical to modern humans. That technology and the fact that Neanderthals were also social beings makes it a little more difficult to explain how they were "outcompeted" by Homo sapiens. I have not seen any theories about how that competition might have included direct incorporation of large numbers of Neanderthals directly into the Homo sapiens population. What are the numbers of Neanderthals who could have been incorporated into the population given the current DNA percentages? I suspect that it could have been large.

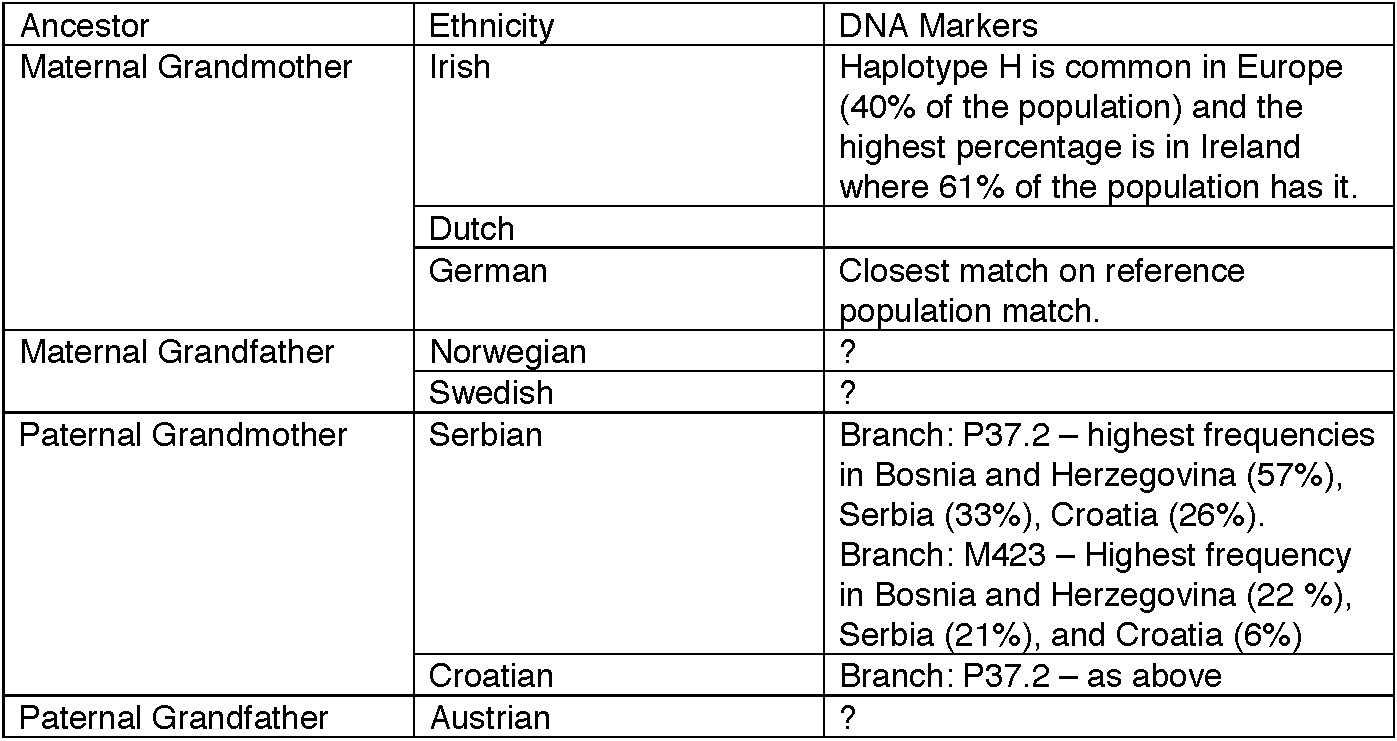

To use an example from my own ancestors, I constructed a table looking at the stated ethnicities of my grandparents. My maternal grandparents had been in the US for a generation longer. My paternal grandmother still spoke and read her native language. My maternal grandfather knew just small bits of Swedish. He taught me a prayer in Swedish but did not know the translation and neither do I. Small customs usually having to do with celebrations and food persisted to a small degree but on the balance my family was Americanized. Comparing the stated ethnicities of my grandparents to DNA markers results in a couple of matches, but as many question marks.

Will there come a time when genetics will allow for better probability statements about who might inherit what disease? Given the fact that my haplotypes occur in less than 1% of the current NatGeo database of over 650,000 subject - maybe. But that depends on a lot more study and a medical record descriptor about presumed ethnicity has very little to do with it. There is a related issue about how the science of paleogenetics can be politicized like any other branch of science. Chris Stringer wrote an excellent commentary about this in Nature. He observed a trend speculating that some genomes were more "modern" than others based on their content of "ancient" DNA. He summarizes this well in two sentences:

"Some of us have more DNA from archaic populations than others, but the great majority of our genes, morphology and behavior derives from our common African heritage. And what unites us should take precedence over that which distinguishes us from each other."

The current evidence also seems to suggest that the migration out of Africa is only part of the story. The identical FOXP2 gene found in both Neanderthals and modern humans, suggests a common ancestor long before the African migration. There are currently 7 billion people on earth. The processing power of the human brain means that there are 7 billion unique conscious states. It should not be too difficult to imagine that isolated groups of humans in in recent times will result in different appearances, customs and practices. The all too human characteristic of promoting the interests of these groups even to the point of warfare against others seems to be a common element of human consciousness.

A more widespread appreciation that these distinctions are by convention only might moderate a tendency for groups to see themselves as different or "better" than other groups of modern humans. That leap of consciousness will hopefully happen in future generations.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

Supplementary 1: One of the most striking aspects of this project is the economics of it all. Over 680,000 people willing to pay $200 apiece for this information. Researchers take note. This may be a new way to fund research and generate large amounts of data at the same time. You probably need a willing department head, IT department, and IRB. There is also a question of collaboration. Is there any correlate between mental illnesses and the genomes of the Neanderthals and Denisovans? If I have a well characterized sample of research subjects with a specific problem does it make sense to look at that issue?

Supplementary 2: There are currently only 19 references to the issues of ancient DNA in Medline at this time. Seems like another good area for research.

Supplementary 3: My old high school biology text was ahead of its time in another way. I remember that it predicted that the human race would eventually appear to be uniform due to increased mobility and intermixing of different races.

Supplementary 4: The infographic at the top of this post was generated by the National Geographic Genographic Project based on my DNA sample.

Supplementary 5: The evidence of bias against Neanderthals in popular culture is significant. My first thought was the Geico commercials based on the premise: " three pre-historic men who must battle prejudice as they attempt to live as normal thirty somethings in modern Atlanta". Even the Wiki piece refers to them as "Neanderthal-like". Wikipedia has interesting references on this page and also a separate page entitled "Neanderthals in popular culture."

Supplementary 6: Updated NatGeo infographic accessed on April 9, 2016. NatGeo knows how to make a world class infographic. Note that the sample size has gone from 678,632 to 742,652. The remaining details are about the same but there is more updated information on the web site.

References:

Monday, September 15, 2014

Will The Real Neuropsychiatrists Please Stand Up?

Recent dilemma - one of several people around the state who consult with me on tough cases called looking for a neuropsychiatrist. He had called earlier and I advised him what he might discuss with the patient's primary care physicians that might be relevant. I suggested a test that turned up positive and in and of itself could account for the subacute cognitive and behavioral changes being observed by many people who know the patient well. I got a call back today requesting referral to a neuropsychiatrist and responded that I don't really know of any. I consider myself to be a neuropsychiatrist but do not know of other psychiatrists who practice in the same way. There is one neuropsychiatrist who practices at the state hospital and is restricted to seeing those inpatients. There is one who sees primarily developmentally disabled persons with significant psychiatric comorbidity. There are several who practice strictly geriatric psychiatry. One of the purposes of this post is to see if there are any neuropsychiatrists in Minnesota. My current employment situation precludes me from seeing any neuropsychiatry referrals.

Neuropsychiatry is a frequently used term that is the subject of books and papers. Several prominent psychiatrists were identified as neuropsychiatrists. I went back to an anniversary celebration for the University of Wisconsin Department of Psychiatry and learned that early on it was a department of neuropsychiatry. It turns out that the Department of Neuropsychiatry was established in 1925 and in 1956 it was divided into separate departments of Psychiatry and Neurology. One of the key questions is whether neuropsychiatry is an historical term or whether it has applications today. The literature of the field would suggest that there is applicability with several texts using the term in their titles, but many don't even mention the word psychiatry. As an example, a partial stack from my library:

A Google Search shows hits for Neuropsychiatry and basically flat during a time when Neuroscience has taken off. Both of them are dwarfed by Psychoanalysis, but much of the psychoanalytical writing has nothing to do with psychiatry or medicine.

What does it mean to practice neuropsychiatry? Neuropsychiatrists practice in a number of settings. For years I ran a Geriatric Psychiatry and Memory Disorder Clinic. Inpatient psychiatry in both acute care and long term hospitals can also be practice settings for neuropsychiatrists. The critical factor in any setting is whether there are systems in place that allow for the comprehensive assessment and treatment of patients. By comprehensive assessment, I mean a physician who is interested and capable of finding out what is wrong with a person's brain. In today's managed care world a patient could present with seizures, acute mental status changes, delirium, and acute psychiatric symptoms and find that they are treated for an acute problem and discharged in a few days - often without seeing a neurologist or a psychiatrist. There may be no good explanations for what happened. The discharge plan may be that the patient is supposed to follow up in an outpatient setting to get those answers. That certainly is possible, but a significant number of people fall through the cracks. There are also a significant number of people who never get an answer and a significant number who should never had been discharged in the first place.

Who are the people who might benefit from neuropsychiatric assessment? Anyone with a complex behavioral disorder that has resulted from a neurological illness or injury. That can include people with a previous severe psychiatric disability who have acquired the neurological illness. It can also include people with congenital neurological illnesses or injuries. One of the key questions early on in some of these processes is whether they are potentially reversible and what can be done in the interim. Some of the best examples I can think of involve neuropsychiatrists who have remained available to these patients over time to provide ongoing consultation and treatment recommendations. In some cases they have assumed care in order to prevent the patient from receiving unnecessary care form other treatment providers. Aggression is a problem of interest in many people with neurological illness because it often leads to destabilization of housing options and results in a person being placed in very suboptimal housing. Treatment can often reverse that trend or result in a trained and informed staff that can design non-medical interventions to reduce aggression.

What is a reasonable definition? According to the American Neuropsychiatric Association neuropsychiatry is "the integrated study of psychiatric and neurologic disorders". Their definition goes on to point out that specific training is not necessary, that there is a significant overlap with behavioral neurology and that neuropsychiatry can be practiced if one seeks "understanding of the neurological bases of psychiatric disorders, the psychiatric manifestations of neurological disorders, and/or the evaluation and care of persons with neurologically based behavioral disturbances." That is both a reasonable definition and a central problem. In clinical psychiatry for example, if a patient with bipolar disorder has a significant stroke what happens to their overall plan of care from a psychiatric perspective? In many if not most cases, the treatment for bipolar disorder is disrupted leading to a prolonged period of disability and destabilization. Neuropsychiatrists and behavioral neurologists practice at the margins of clinical practice. That is not predicated on the importance of the area, but the business aspects of medicine today. If psychiatry and neurology departments are established around a specific encounter and code, frequent outliers are not easily tolerated. Patients with either neuropsychiatric problems or problems in behavioral neurology can quickly become outliers due to the need to order and review larger volumes of tests, collect greater amounts of collateral information, and analyze separate problems. In any managed clinic, the average visit is typically focused on one problem. Neuropsychiatric patients often have associated communication, movement, cognitive and gross neurological problems. Some of these problems may need to be addressed on an acute or semi-acute basis.

Where are they in the state? Neuropsychiatrists are probably located in areas outside of typical clinics. By typical clinics I mean those that are outside of the HMO and managed care sphere. They can be identified as clinics that are managed by physicians rather than MBAs. The three largest that come to mind are the Mayo Clinic, the Cleveland Clinic, and the Marshfield Clinic. Apart from those clinics there are many free standing neurology and fewer free standing neuropsychiatric clinics. Speciality designations in geriatric psychiatry or neurology, dementias, developmental disorders, and other conditions that overlap psychiatry and neurology are good signs. There will also be psychiatrists in institutional and correctional settings with a lot of experience in treating difficult to treat neuropsychiatric problems. There may be a way to commoditize this knowledge and get it out to a broader audience. Since starting this blog I have pointed out the innovative pan in place thought the University of Wisconsin and the Wisconsin Alzheimer's Institute (WAI) network of clinics. They have impressive coverage throughout the state and provide a model for how at least one aspect of neuropsychiatry can be made widely available through collaboration with an academic program.

What should the profession be doing about it? The American Psychiatric Association (APA) and just about every other medical professional organization has been captive to "cost effective" rhetoric. IN psychiatry that comes down to access to 20 minutes of "medication management" versus comprehensive assessment of a physician who knows the neurology and medicine and how it affects the brain. The new hype about collaborative care takes the psychiatrist out of the loop entirely. The WAI protocol specifies the time and resource commitment necessary to run a clinic that does neuropsychiatric assessments. I have first hand experience with the cost effective argument because my clinic was shut down for that reason. We adhered to the WAI protocol.

What the APA and other medical professional organizations seems to not get is that if you teach people competencies in training, it is basically a futile exercise unless they can translate that into a practice setting. The WAI protocol provides evidence of the time and resource commitment necessary to support neuropsychiatrists. It is time to take a stand and point out that a psychiatric assessment, especially if it has a neuropsychiatric component takes more than a 5 minute checklist and treatment based on a score. A closely related concept is that total time spent does not necessarily equate with the correct or a useful diagnosis. I have assessed and treated people who have had 4 hours of neuropsychological testing and that did not result in a correct diagnosis.

If those changes occurred, I might be able to advise people who ask that there are more than two neuropsychiatrists in the state.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

1: Benjamin S, Travis MJ, Cooper JJ, Dickey CC, Reardon CL. Neuropsychiatry and neuroscience education of psychiatry trainees: attitudes and barriers. Acad Psychiatry. 2014 Apr;38(2):135-40. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0051-9. Epub 2014 Mar 19. PubMed PMID: 24643397.

Neuropsychiatry is a frequently used term that is the subject of books and papers. Several prominent psychiatrists were identified as neuropsychiatrists. I went back to an anniversary celebration for the University of Wisconsin Department of Psychiatry and learned that early on it was a department of neuropsychiatry. It turns out that the Department of Neuropsychiatry was established in 1925 and in 1956 it was divided into separate departments of Psychiatry and Neurology. One of the key questions is whether neuropsychiatry is an historical term or whether it has applications today. The literature of the field would suggest that there is applicability with several texts using the term in their titles, but many don't even mention the word psychiatry. As an example, a partial stack from my library:

A Google Search shows hits for Neuropsychiatry and basically flat during a time when Neuroscience has taken off. Both of them are dwarfed by Psychoanalysis, but much of the psychoanalytical writing has nothing to do with psychiatry or medicine.

What does it mean to practice neuropsychiatry? Neuropsychiatrists practice in a number of settings. For years I ran a Geriatric Psychiatry and Memory Disorder Clinic. Inpatient psychiatry in both acute care and long term hospitals can also be practice settings for neuropsychiatrists. The critical factor in any setting is whether there are systems in place that allow for the comprehensive assessment and treatment of patients. By comprehensive assessment, I mean a physician who is interested and capable of finding out what is wrong with a person's brain. In today's managed care world a patient could present with seizures, acute mental status changes, delirium, and acute psychiatric symptoms and find that they are treated for an acute problem and discharged in a few days - often without seeing a neurologist or a psychiatrist. There may be no good explanations for what happened. The discharge plan may be that the patient is supposed to follow up in an outpatient setting to get those answers. That certainly is possible, but a significant number of people fall through the cracks. There are also a significant number of people who never get an answer and a significant number who should never had been discharged in the first place.

Who are the people who might benefit from neuropsychiatric assessment? Anyone with a complex behavioral disorder that has resulted from a neurological illness or injury. That can include people with a previous severe psychiatric disability who have acquired the neurological illness. It can also include people with congenital neurological illnesses or injuries. One of the key questions early on in some of these processes is whether they are potentially reversible and what can be done in the interim. Some of the best examples I can think of involve neuropsychiatrists who have remained available to these patients over time to provide ongoing consultation and treatment recommendations. In some cases they have assumed care in order to prevent the patient from receiving unnecessary care form other treatment providers. Aggression is a problem of interest in many people with neurological illness because it often leads to destabilization of housing options and results in a person being placed in very suboptimal housing. Treatment can often reverse that trend or result in a trained and informed staff that can design non-medical interventions to reduce aggression.

What is a reasonable definition? According to the American Neuropsychiatric Association neuropsychiatry is "the integrated study of psychiatric and neurologic disorders". Their definition goes on to point out that specific training is not necessary, that there is a significant overlap with behavioral neurology and that neuropsychiatry can be practiced if one seeks "understanding of the neurological bases of psychiatric disorders, the psychiatric manifestations of neurological disorders, and/or the evaluation and care of persons with neurologically based behavioral disturbances." That is both a reasonable definition and a central problem. In clinical psychiatry for example, if a patient with bipolar disorder has a significant stroke what happens to their overall plan of care from a psychiatric perspective? In many if not most cases, the treatment for bipolar disorder is disrupted leading to a prolonged period of disability and destabilization. Neuropsychiatrists and behavioral neurologists practice at the margins of clinical practice. That is not predicated on the importance of the area, but the business aspects of medicine today. If psychiatry and neurology departments are established around a specific encounter and code, frequent outliers are not easily tolerated. Patients with either neuropsychiatric problems or problems in behavioral neurology can quickly become outliers due to the need to order and review larger volumes of tests, collect greater amounts of collateral information, and analyze separate problems. In any managed clinic, the average visit is typically focused on one problem. Neuropsychiatric patients often have associated communication, movement, cognitive and gross neurological problems. Some of these problems may need to be addressed on an acute or semi-acute basis.

Where are they in the state? Neuropsychiatrists are probably located in areas outside of typical clinics. By typical clinics I mean those that are outside of the HMO and managed care sphere. They can be identified as clinics that are managed by physicians rather than MBAs. The three largest that come to mind are the Mayo Clinic, the Cleveland Clinic, and the Marshfield Clinic. Apart from those clinics there are many free standing neurology and fewer free standing neuropsychiatric clinics. Speciality designations in geriatric psychiatry or neurology, dementias, developmental disorders, and other conditions that overlap psychiatry and neurology are good signs. There will also be psychiatrists in institutional and correctional settings with a lot of experience in treating difficult to treat neuropsychiatric problems. There may be a way to commoditize this knowledge and get it out to a broader audience. Since starting this blog I have pointed out the innovative pan in place thought the University of Wisconsin and the Wisconsin Alzheimer's Institute (WAI) network of clinics. They have impressive coverage throughout the state and provide a model for how at least one aspect of neuropsychiatry can be made widely available through collaboration with an academic program.

What should the profession be doing about it? The American Psychiatric Association (APA) and just about every other medical professional organization has been captive to "cost effective" rhetoric. IN psychiatry that comes down to access to 20 minutes of "medication management" versus comprehensive assessment of a physician who knows the neurology and medicine and how it affects the brain. The new hype about collaborative care takes the psychiatrist out of the loop entirely. The WAI protocol specifies the time and resource commitment necessary to run a clinic that does neuropsychiatric assessments. I have first hand experience with the cost effective argument because my clinic was shut down for that reason. We adhered to the WAI protocol.

What the APA and other medical professional organizations seems to not get is that if you teach people competencies in training, it is basically a futile exercise unless they can translate that into a practice setting. The WAI protocol provides evidence of the time and resource commitment necessary to support neuropsychiatrists. It is time to take a stand and point out that a psychiatric assessment, especially if it has a neuropsychiatric component takes more than a 5 minute checklist and treatment based on a score. A closely related concept is that total time spent does not necessarily equate with the correct or a useful diagnosis. I have assessed and treated people who have had 4 hours of neuropsychological testing and that did not result in a correct diagnosis.

If those changes occurred, I might be able to advise people who ask that there are more than two neuropsychiatrists in the state.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

1: Benjamin S, Travis MJ, Cooper JJ, Dickey CC, Reardon CL. Neuropsychiatry and neuroscience education of psychiatry trainees: attitudes and barriers. Acad Psychiatry. 2014 Apr;38(2):135-40. doi: 10.1007/s40596-014-0051-9. Epub 2014 Mar 19. PubMed PMID: 24643397.

Wednesday, August 13, 2014

The Stanley Center Grant

The details of this grant and some of the history of previous grants are given in this press release from the Broad Institute. A few of the details include the fact that the Broad Institute has about 150 scientists working on the genetics of severe mental illnesses. That focus includes detailing the genetic basis of these disorders, a more complete elaboration of the the pathways involved and developing molecules that can modify these pathways as a foundation for more effective medical treatment. The focus of this group is on severe psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, autism and attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. It was also the single largest donation for psychiatric research - ever.

Any search on research grants over the past decade will produce thousands of research articles that were funded by the Stanley Foundation. The press release details the fact that grants from the Stanley Foundation have been incremental and that they are obviously monitored for progress by the grantees who are satisfied with the progress being made. That has not stopped some critics from suggesting that the money is basically either wasted, that it could be better used for symptom control, or that it would be more useful for research in symptom control. My goal here is to question some of these arguments about basic psychiatric research in much the same way that I question the arguments that usually attack psychiatric practice and clinical research. My speculation is that the underlying premises in both cases are very similar.

The basic arguments about whether it is a good idea to fund basic science research as it applies to psychiatry range from speculation about whether or not it might be useful to the fact there are more urgent needs to funding on the clinical side. Many of these arguments come down to the idea of symptom management versus a more scientific approach to the patient. There are few areas in medicine that have a purely scientific approach to the patient at this time. The more clearcut examples would be locating a lesion somewhere in the body, performing a biopsy and making tissue diagnosis. That is an example of the highly regarded "test" to prove an illness that seems to be a popular idea about scientific medicine. But in that case the science can run out at several levels. The diagnosis depends on correctly sampling the lesion and that can come down to the skill of the sampler. It depends on the agreement of pathologists making the tissue diagnosis. The tissue diagnosis may be irrelevant to the health of the patient if there are no treatments for the diagnosed illness.

In many cases in medicine, treatment depends on symptom recognition and monitoring. In some cases there are tests of basic anatomy or function. A good example is asthma. As I have previously posted here (see Myth 4), the majority of asthmatics have inadequate control of asthma and the approach to asthma is generally symptom control. The current basic science of asthma depends on identifying genes and gene products that will allow for more specific treatment of the underlying pathophysiology and there are surprising similarities with mental illnesses. For example, there is no single asthma gene. The genetics of the various aspects of asthma pathophysiology including the degree to which it can be treated is assumed to be polygenic in the same manner as the genetics of severe psychiatric disorders. The only difference being that a larger portion of the human genome is dedicated to brain proteins (personal correspondence with experts puts that figure as high as 25%). Genome wide association studies of severe asthma can have as much difficulty identifying candidate genes that reach statistical significance. Any thought experiment comparing the reference pathway for asthma to any number of similar pathways that are operative for brain plasticity, human consciousness and the variants we call mental illnesses will show that there are surprising few specific interventions for asthma signaling and that signaling occurring in the brain is even more complex. The reason why we have impressive brain function is structural complexity at cellular, structural and biochemical pathway levels. And yet the rhetoric of critics usually considers asthma as a disease to be more legitimate than psychiatric disorders and the lungs are apparently considered a more legitimate target for research funding than the brain.

What are the critics saying? Allen Frances, MD DSM critic has decided that neuroscience research may be so complicated that the $650 million dollar grant may be a drop in the bucket in sorting out the basic science. He suggests:

"But there is a cruel paradox when it comes to mental disorders. While we chase the receding holy grail of future basic science breakthrough, we are shamefully neglecting the needs of patients who are suffering right now. It is probably on average worse being a patient with severe mental illness in the US now than it was 150 years ago. It is certainly much worse being a patient with severe mental illness in the US as compared to most European countries."

My experience in psychiatry is clearly much different from Dr. Frances. Although I am probably at least a decade younger, I can remember a time when there was no treatment at all. As a child I heard the stories of my great aunt working in a county sanatorium full of patients with tuberculosis and severe mental illnesses. This was state-of-the-art treatment before the era of psychopharmacology. Large numbers of institutionalized patients went there and many never left unless they had a mood disorder that suddenly remitted or they received electroconvulsive therapy. Those leaving often ended up on county "poor farms" for the indigent. Contrary to Dr. Frances observations that was about 50 years ago. Going back earlier than that I consider Shorter to be definitive. In his text he describes what describes what it was like to have a psychotic disorder before the asylum era in many countries of the world and concludes:

"In a world without psychiatry, rather than being tolerated or indulged, the mentally ill were treated with a savage lack of feeling. Before the advent of the therapeutic asylum, there was no golden era, no idyllic refuge for those supposedly deviant from the values of capitalism. To maintain otherwise is a fantasy." (p4)