I think about discussions I used to have over lunch with

several specialists. Our typical group consisted of 3 GI docs, 1 or 2

Infectious Disease docs, a nephrologist and me.

We usually talked about movies but one day it turned to pancreatic

cancer. The question became – if you

could screen for it would you? This

discussion happened back in the 1990s and the consensus at that time was no. One of the pieces of evidence offered was the

poor prognosis after surgical intervention – irrespective of the time of

diagnosis.

I personally know 10 people who were diagnosed with

pancreatic cancer. Four of them are on the paternal side of my family and one

is a first degree relative – my sister. My earliest recollection of the disease

was visiting my paternal aunt who lived a few blocks from my family. Back in the 1950s, there was no useful imaging

and diagnoses typically depended on exploratory surgery and direct tissue

sampling. People who lived in remote areas did not travel to large referral

centers to see specialists. You lived and died based on the skill of local

physicians – some who had surgical training but were not technically general

surgeons. Blood banking also did not exist and my father and uncle had to

donate blood for my aunt. Nine of the 10 people I have known with pancreatic

cancer are deceased some of them within weeks to months of the diagnosis. My sister has been a trail blazer. After a fortuitous diagnosis while being

scanned for gallbladder disease, pancreatic cancer was diagnosed and she

underwent radiation therapy, chemotherapy, a Whipple procedure, and maintenance therapy with a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor. She saw an oncologist who recommended genetic

testing and discovered she had an ATM gene variant. The genetic counselor she

was seeing at the time recommended that all her siblings get tested for the

same gene and to see if their children also needed to be tested.

ATM stands for “ataxia telangiectasia mutated.” Ataxia telangiectasia (AT) is a hereditary

degenerative ataxia that occurs in 1 in 20K to 100K live births (3,4). Gait problems and truncal instability occurs

in the first decade of life followed by progressive ataxia. Telangiectasias

starts at about age 5 and are most evident in the conjunctive but can occur at

various sites on the body. Immunodeficiency is noted with frequent respiratory

infections. Humoral and cell mediated

immunity are affected as evidenced by decreased immunoglobulins and

lymphocytopenia. AT is also associated with an increased frequency of cancers beginning

with hematological malignancies in childhood and different malignancies as

adults (6). Lifespan with AT is

decreased but is now more than 25 years with supportive measures.

The mutations causing AT were discovered as mutations in

the ATM gene in the late 20th century. The ATM gene is located on chromosome 11, and

the gene product is a serine-threonine kinase involved in DNA repair (5). Like

most human genes there are a large

number of mutations and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Those mutations associated with AT are

insertions, deletions, missense, and truncations. These mutations can lead to absence or loss

of function ATM protein. In my case the

lab report read:

Variant Details:

ATM, Exon 10,

c.1564_1565del (p.Glu522Ilefs*43), heterozygous, PATHOGENIC

This sequence change

creates a premature translational stop signal (p.Glu522Ilefs*43) in the ATM

gene. It is expected to result in an absent or disrupted protein product.

Loss-of-function variants in ATM are known to be pathogenic (PMID: 23807571,

25614872).

This premature

translational stop signal has been observed in individual(s) with breast cancer

and ataxia-telangiectasia (PMID: 9000145, 9463314, 10330348, 10817650, 12497634,

21965147, 27083775).

In order to appreciate how the ATM protein works – a brief

review of cell biology is in order.

Cells reproduce according to a cell cycle with various components. The

protein components and cell signaling of that cycle were discovered in the past

40 years. The cell cycle has checkpoints

designed to stop the cycle and repair any DNA that is discovered as defective

along the way. ATM is one of the proteins that modulates that process. Functional ATM protein means that it is less

likely that damaged DNA is passed along in new cell lines and that reduces the

risk of cancer. ATM mutations are

associated with increase risk for pancreatic, ovarian, breast, and prostate

cancer and as previously noted – malignancies associated with AT. That is the mile high version of checkpoint

and checkpoint proteins. If you want a

more detailed explanation, put it in the comments section and I will add more.

This mechanism is interesting to consider when thinking

about genomic versus environmental effects. Peak incidence for new diagnoses of

pancreatic cancer occurs during the 70s. If you have a defective DNA repair

mechanism – is this the time where those defects accumulate to the point of

creating malignancy? How is

your history of avoiding carcinogens like alcohol and tobacco smoke relevant to

that probability? What about the

protective effects of antioxidants and exercise? At some point does a partially

functional ATM protein protect against cancer or is the fully functional

protein required?

The referral process in my own primary care clinic went

smoothly when I told my internist about my sister’s diagnosis. I got an online

appointment with a genetic counselor and when the results came back – she told

me there was a 10-15% chance of pancreatic cancer and one clinic that did risk surveillance

at Mayo. She asked me if I was

interested and why. She also advised me

that there are currently loopholes in the law that allow some companies to

discriminate against you based on genetic testing. After discussing what those

companies did – I told her I was not concerned about it and she made the

referral. I met with the

gastroenterologist who headed the clinic, signed up for additional research

protocols, had an MRI scan and just completed an upper GI endoscopy with

ultrasound (US). The ultrasound device

is in the head of the gastroscope and it needs to be positioned in various

areas of the stomach and duodenum to visualize the entire pancreas. The US

procedure was also set up to proceed with a fine needle biopsy of the pancreas

– but no lesions were noted and no biopsy was necessary. If a biopsy is

required it is done through the wall of the stomach or duodenum. Current screening is on an annual basis and

the orders have already been placed for next year.

Getting back to the answer to the question posed in the

title - it comes down to genes. One of the cultural myths in the US is that

you always bear some level of responsibility for your disease. Recall any discussion

about this with friends or family: “Did you hear that your classmate died last

week from X?” The next question or

comment is likely to be – “well he (smoked, drank, never exercised, was obese,

didn’t take care of himself, never saw a doctor, etc.”). There always must be

an explanation for your old classmate dying prematurely and it is rarely biological. Even though everybody in

town with the same risk factors – outlived him by 20 years. The stark reality is that it does not take a

risk factor-based analysis. All it takes is a gene (or many genes) that code

for the disease either directly or indirectly.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

References:

1: Armstrong SA,

Schultz CW, Azimi-Sadjadi A, Brody JR, Pishvaian MJ. ATM Dysfunction in

Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma and Associated Therapeutic Implications. Mol Cancer

Ther. 2019 Nov;18(11):1899-1908. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-19-0208. PMID:

31676541; PMCID: PMC6830515.

2: Klein AP.

Pancreatic cancer epidemiology: understanding the role of lifestyle and

inherited risk factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jul;18(7):493-502.

doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00457-x. Epub 2021 May 17. PMID: 34002083; PMCID:

PMC9265847.

The risk of death from pancreatic cancer rises

dramatically with age from <2 deaths per 100,000 person-years for

individuals in the USA aged 35–39 years to >90 deaths per 100,000

person-years for individuals aged >80 years.

3: Subramony SH, Xia

G. Disorders of the cerebellum, including the degenerative ataxias. In:

Neurology in Clinical Practice (7th edition). RB Daroff, J

Jancovic, JC Mazziotta, SL Pomeroy (eds). Elsevier, London, 2016. p: 1468-1469.

4: Rothblum-Oviatt,

C., Wright, J., Lefton-Greif, M.A. et al. Ataxia telangiectasia: a review.

Orphanet J Rare Dis 11, 159 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-016-0543-7

5: ATM

serine/threonine kinase [ Homo sapiens (human) ]

Gene ID: 472, updated on 12-Mar-2023

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/472

6: Hsu F, Roberts

NJ, Childs E, et al. Risk of Pancreatic Cancer Among Individuals With

Pathogenic Variants in the ATM Gene. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(11):1664–1668.

doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.3701

“The cumulative risk of pancreatic cancer among

individuals with a germline pathogenic ATM variant was estimated to be 1.1%

(95%CI, 0.8%-1.3%) by age 50 years; 6.3%(95%CI, 3.9%-8.7%) by age 70 years; and

9.5%(95%CI, 5.0%-14.0%) by age 80 years. Overall, the relative risk of

pancreatic cancer was 6.5 (95%CI, 4.5-9.5) in ATM variant carriers compared

with noncarriers.”

7: Trikudanathan G, Lou E, Maitra A, Majumder S. Early detection of pancreatic cancer: current state and future opportunities. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2021 Sep 1;37(5):532-538. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000770. PMID: 34387255; PMCID: PMC8494382.

8: Oh SY, Edwards A, Mandelson MT, Lin B, Dorer R, Helton WS, Kozarek RA, Picozzi VJ. Rare long-term survivors of pancreatic adenocarcinoma without curative resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2015 Dec 28;21(48):13574-81. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i48.13574. PMID: 26730170; PMCID: PMC4690188.

9: Overbeek KA, Goggins MG, Dbouk M, Levink IJM, Koopmann BDM, Chuidian M, Konings ICAW, Paiella S, Earl J, Fockens P, Gress TM, Ausems MGEM, Poley JW, Thosani NC, Half E, Lachter J, Stoffel EM, Kwon RS, Stoita A, Kastrinos F, Lucas AL, Syngal S, Brand RE, Chak A, Carrato A, Vleggaar FP, Bartsch DK, van Hooft JE, Cahen DL, Canto MI, Bruno MJ; International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening Consortium. Timeline of Development of Pancreatic Cancer and Implications for Successful Early Detection in High-Risk Individuals. Gastroenterology. 2022 Mar;162(3):772-785.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.10.014. Epub 2021 Oct 19. PMID: 34678218.

10: Søreide K, Ismail W, Roalsø M, Ghotbi J, Zaharia C. Early Diagnosis of Pancreatic Cancer: Clinical Premonitions, Timely Precursor Detection and Increased Curative-Intent Surgery. Cancer Control. 2023 Jan-Dec;30:10732748231154711. doi: 10.1177/10732748231154711. PMID: 36916724; PMCID: PMC9893084.

"The overall poor prognosis in pancreatic cancer is related to late clinical detection. Early diagnosis remains a considerable challenge in pancreatic cancer. Unfortunately, the onset of clinical symptoms in patients usually indicate advanced disease or presence of metastasis."

11: National Center for Biotechnology Information. ClinVar; [VCV000127340.60], https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/VCV000127340.60 (accessed March 19, 2023).

Graphics:

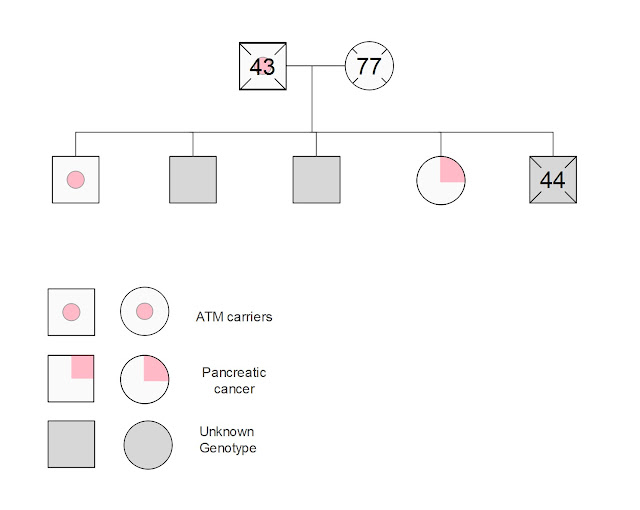

I drew that genogram of my immediate family using EDraw Max. I am one of the two siblings that tested positive for the ATM variant. My other siblings have not been tested.