For starters GLP-1 agonists are drugs like Ozempic and Weygovy. See this post for a current list. It is hard not to hear about them since they are heavily hyped in just about every form of media. They are being touted as a cure for just about everything. Various celebrities are either promoting them or denying that a dramatic weight loss was associated with their use. Some in the weight loss and exercise industry are pushing back with statements about side effects and rapid weight gain if you ever stop taking them. The sales of these drugs is a windfall for the pharmaceutical industry and current pricing means that other businesses that make money from rationing access to medical care and medications will be trying to prevent their use. I thought I would post a contrast today between the latest review of conditions these medications have been researched for and a new paper that suggests they may increase the frequency of psychiatric disorders.

The rest of the title comes from my experience in many

medical settings over the decades. Any

time a medication is commonly prescribed you can count on someone saying “We

should just put it in the drinking water.”

Examples over the years have been amoxicillin, H-2 blockers like

ranitidine, statins, beta blockers, lorazepam, and even haloperidol. It all depends on the prescription frequency

in a particular setting. At the rate GLP-1 agonists have been hyped - somebody

is saying it somewhere. The irony in

that statement is that many medications are now in the water supply and not

doing anything for anybody.

When I describe this group of drugs as hyped that is exactly

what I mean. The only comparable hype has been for cannabis and psychedelics/hallucinogens. Typical newspaper headlines about GLP-1s say

they are wonder drugs and go on to describe them as indicated for several

conditions ranging from addiction to Alzheimer’s disease. Currently 5.4% of all medication

prescriptions in the United States are for GLP-1 agonists. These drugs have been

around for 20 years and during that time transitioned from use primarily

for Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 to weight loss. Despite all the clinical trials

and experience with them I do not think the final verdict is in and the main

papers relevant to this post will illustrate why.

The first paper (1) is a large observational study using

databases from the Veterans Administration (VA) health care system (1). The authors describe the rationale of their

study as looking at the real-world outcomes of the use of GLP-1 agonists – both

the positive effects and adverse outcomes. They had an N of 1,955,135 followed

for a median of 3.68 years looking at 175 health outcomes. The authors use an interesting

methodology. Patients were recruited

based on incident use of a medications for Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) between

October 1, 2017 and December 31, 2023.

That created 4 groups based on the medical treatment of T2DM) including GLP-1 agonists

(N= 232,210), sulfonylureas (N= 247,146), Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4i)

inhibitors (N= 225,116), and SGLT2i inhibitors (sodium-glucose cotransporter 2

inhibitors) (N= 429,172). There was also

a treatment as usual (TAU) group (N= 1,513,896) with Type 2 DM who took

non-GLP-1 antihyperglycemics between the study dates of October 1, 2017 and

December 31, 2023. As a point of reference,

I have included a table of the medications in each class used for T2DM.

|

Glucagon-like

peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists |

exenatide

(Bydureon) exenatide

(Byetta) liraglutide

(Victoza) liraglutide

(Saxenda) dulaglutide

(Trulicity) semaglutide

(Wegovey) semaglutide

(Ozempic) semaglutide

(Rybelsus) tirzepatide

(Mounjaro) tirzepatide

(Zepbound) |

|

|

|

|

Sulfonylureas |

Glipizide Glimepiride Glyburide |

|

|

|

|

dipeptidyl peptidase

4 (DPP4) inhibitors |

alogliptin (Nesina,

Vipidia) sitagliptin

(Januvia) saxagliptin

(Onglyza) linagliptin

(Tradjenta) |

|

|

|

|

sodium−glucose

cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors) |

bexagliflozin

(Brenzavvy) canagliflozin

(Invokana) dapagliflozin

(Farxiga) empagliflozin

(Jardiance) ertugliflozin

(Steglatro) |

This study was designed to assess groups on 175 health

outcomes from these treatment cohorts compared with two control groups. One control group was a composite of equal

numbers of diabetic subjects using oral hypoglycemics and the other control

groups was diabetics who continued GLP-1 agonists that they had already been

started on. Results varied but generally

the health outcomes measured were significantly improved on the GLP-1 agonists

compared with the controls and across categories. For example, when GLP-1 agonists were compared

with the sulfonylurea, DPP4, and SGLT2 classes outcomes were improved in

13.14%, 17.14%, and 11.43% of the outcomes respectively.

Risk of adverse outcomes were 8%, 7.43%, and 16.57% in the

same order. Those adverse events in

aggregate included: nausea and vomiting, gastroesophageal reflux disease

(GERD), sleep disturbances, bone pain, abdominal pain, hypotension, headaches,

nephrolithiasis, and anemia.

When comparing the addition of GLP-1s to treatment as usual

(the composite control) better outcomes were observed in 24% and increased risk

of adverse outcomes in 10.86% of outcomes.

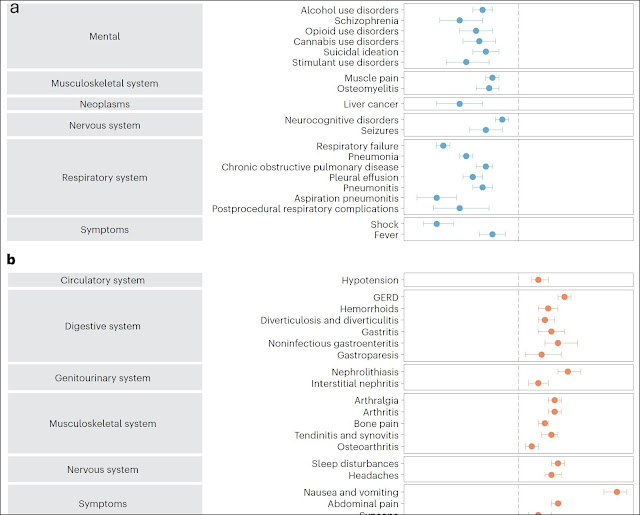

The reduced risk of several CNS disorders were estimated by

hazard ratios and they were modestly decreased for alcohol use disorder,

cannabis use disorder, stimulant use disorder, opioid use disorder, suicidal

ideation of self-injury, bulimia, schizophrenia, seizures and neurocognitive

disorders. Risk reductions were in the

10-16% range.

The authors of this paper use several graphing techniques to present their data. They graphed hazard ratios for both improved and adverse outcomes and made negative log transformed Manhattan plots as a measure of statistical robustness as alternate graphing technique. The paper is open access and I encourage reading the paper to see these data presentations. I included a partial Forest plot at the top of this post to illustrate some of these graphs and the outcomes they measured. The blue dots indicate reduced risk relative to controls and the orange dots indicate increased risk (calculated as hazard ratios (3).

The strength of this study is that it summarizes a large

amount of data across a VA database.

Since it is administrative data it is collected in nonstandard way and

the diagnoses are not necessarily made by experts - this data may not be as robust as a prospective randomized clinical trial. The population was older white veterans and

that may be a factor when considering pleotropic effects. The authors conclude that the GLP-1 agonists

had broad pleotropic effects based on the spectrum of positive results

and preclinical work. They emphasize the

positive results for neuropsychiatric diseases and disorders. They discuss the issue of suicidal behavior

and point out that earlier studies raised concerns to the point that the

European Medicines Agency investigated and found no evidence for causality. This study showed decreased suicidality and

possible antidepressant effects. The

results generally showed significant positive effects on outcomes across major

disease categories with a clear group of adverse effects.

For comparison there is a recent large retrospective cohort study (2) that uses deidentified data on patients from 66 different health care organizations. This appears to be a database with a commercial purpose, but I cannot identify what that purpose might be based on their web site. In their rollover map, most of the deidentified patients in this database are Americans. The study was approved by an IRB in China and I assume that is where the analysis takes place. The study was focused on examining the effects of GLP-1 agonists on patients being treated for obesity. Subjects were selected for a diagnosis of obesity and incident use of a GLP-1 agonist. It was a retrospective cohort analysis similar to the first study but propensity score matching was done to pair treatment subjects more closely with controls. Exclusion criteria included use of any other weight loss drug and any psychiatric diagnosis or significant symptom like suicidality.

The main results of this study are summarized in 3 tables in

the body of the paper (Tables 2, 3, and 4).

Psychiatric outcomes were measured over a period of 5 years and the percentage

of patients with major depression, any anxiety, any psychiatric disorder and

suicidality (ideation or behaviors) we measured at 6 months, 1 year, 3 years,

and 5 years. The cumulative incidences

of disorders and suicidality increased over these intervals. Hazard ratios were calculated compared with

the control population and they were generally doubled.

Results stratified on demographic factors and GLP-1 agonist

potency showed that both sexes had higher than expected psychiatric morbidity

associated with GLP-1 agonist use but that women had significantly higher hazard

ratios across all categories. Age was inversely correlated with older

populations having lower risk of psychiatric comorbidity. Finally, the potency

of the GLP-1 agonist directly correlated with potency of the GLP-1 agonist and

time of exposure. The authors discuss

the limitations of their study and implications for future use and study.

Both studies generally illustrate some of the advantages and problems of conducting

large clinical trials. The numbers in the hundreds of thousands or million plus

range would be very difficult if not impossible to conduct randomized clinical

trials on. It is manageable using the naturalistic

retrospective designs employed here commonly referred to as real world designs. The obvious limiting factor is expense and

the methodological problem of drop outs over time. In these specific cases the first study is selecting

a subject cohort based on a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus type 2 (DMT2) and

the second obesity. Both are

heterogeneous populations with some overlap.

If I was influenced at all by some of the current psychiatric literature,

I might suggest transdiagnostic features common to both but the

importance of that term seems inflated relative to common medical diagnostic

formulations. Instead - I will use the

parlance of medical trials and point out that there are signals in both papers. Those signals are both good and not so

good. In the first paper there were

clearly improvements in many medical outcomes when T2DM was treated with GLP-1

agonists in about 25% of the conditions studied and adverse outcomes in about

10%. Improvement occurred in conditions

outside of the endocrine/metabolic sphere including some psychiatric conditions.

In the second study, significant increases in psychiatric conditions were noted

to occur associated with GLP-1 agonist potency and total exposure in a

population selected for obesity treatment.

The authors are careful to point out that obesity and metabolic syndrome

may be a risk factor for mood disorders and they provide an excellent

discussion of how trial design and patient selection may have affected these

results.

When these trials are reported in the news, they are

generally not reported as showing modest results. Side effects are typically ignored. I have not heard anything about the study

that showed that increased rather than decreased psychiatric morbidity may be a

possible outcome. The media generally

reports them as miracle drugs and patients with the best possible

results are given as examples.

GLP-1 agonists are clearly serious medications with

potentially serious adverse effects. The

prescription of these medications requires close monitoring and thorough

patient education. If I was prescribing these medications today - in the informed consent discussion I would include the potential for modest outcomes, potentially increased psychiatric side effects, the general potential for side effects, and why outcomes may be variable. I would also make sure to let people know that long term outcomes at this point are not known with any degree of certainty.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

References:

1: Xie Y, Choi T,

Al-Aly Z. Mapping the effectiveness and risks of GLP-1 receptor agonists. Nat

Med. 2025 Jan 20. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-03412-w. Epub ahead of print. PMID:

39833406.

2: Kornelius E, Huang

JY, Lo SC, Huang CN, Yang YS. The risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidal

behavior in patients with obesity on glucagon like peptide-1 receptor agonist

therapy. Sci Rep. 2024 Oct 18;14(1):24433. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-75965-2.

PMID: 39424950; PMCID: PMC11489776

3: Spruance SL, Reid

JE, Grace M, Samore M. Hazard ratio in clinical trials. Antimicrob Agents

Chemother. 2004 Aug;48(8):2787-92. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.8.2787-2792.2004. PMID:

15273082; PMCID: PMC478551.