For about the past year, I have been using transversed edges per second (TEPS) in my lectures about neurobiology to give a rough estimate of the computing power of the human brain and a rougher estimate of where brain power compares with artificial intelligence (AI). I finally found the detailed information on the AI Impacts web site and wanted to post it here, both for future reference and to possibly generate more interest in this topic for psychiatrists.

I have been interested in human computer comparisons since I gave a Grand Rounds on the topic back in the 1990s. Back then I was very interested in bandwidth in the human brain and trying to calculate it. My basic approach was to look at the major bus systems in the brain and their fiber counts and try to estimate how much information was passing down that bus. In engineering terms a bus is a path that the computer or processors use to communicate with other devices or processors. The rate at which that communication passes down that pathway is a major limitation in terms of computing speed to the rate at which tasks are transmitter to peripheral devices. Engineers typically specify the characteristics of these communication paths. A good example are the standard USB connectors on your computer. Today there are USB 2.0 and USB 3.0 connectors. The USB 2.0 devices can support a data transfer rate of 480 Mbps or 60 MBs. The USB 3.0 connection supports 5 gbps or 640 MBs.

In the work I was doing in the 1990s, I looked at the major structures in the brain that I considered to be bus-like the fascicles and the corpus callosum. Unfortunately there were not many fiber count estimates for these structures. It turns out that very few neuroanatomists count fibers or neurons. The ones who do are very exacting. The second issue was the information transfer rate. If fiber counts could be established was there any reliable estimate of the information contained in spikes. I was fortunate at the time that a book came out that was somewhat acclaimed at the time called Spikes. In it the authors, attempted to calculate the exact amount of information in these spikes. They used a fast Fourier transform (FFT) methodology that I was familiar with from quantitative EEG (QEEG). From available data t the time I was limited to calculating the bandwidth of the corpus callosum. I used a fiber (axon) count of 200 million. It turns out that the corpus callosum is a heterogeneous bus with about 160,000 very large fibers. Using a bit rate of 300 bits/sec for each spiking neuron multiplied by the entire bus results in a total of 60 Gbs. I had a preliminary calculation but realized I had about another 11 white matter fiber tracts connecting lobes, hemispheres and the limbic system. I did not have the fiber counts for any of these structures and the top neuroanatomist in the world could not help me.

Then I found an interesting question posted in a coffee shop. In the process of investigating it, I found some preliminary data about a group that was using a calculation called tranversed edges per second (TEPS) and showing at least on a preliminary basis that the human brain is currently calculating at a rate that is currently on par with supercomputers. I found additional papers from the group, just this week. The articles can be read and understood by anyone. They are interesting to read to look at the authors basic assumptions as well as how they might be wrong. They give rough estimates in some cases about how large the error might be if their assumptions are wrong. They provide detailed references and footnotes for their assumptions and calculations.

Their basic model assumes that the human brain is comprised of interconnected nodes in the same way that a supercomputer connects with processors or clusters of processors. This basic pattern has been described in some situations in the brain but the details are hard to find. There is also a question about the level for analysis of the nodes. For example are large structures the best choice and if not how many smaller networks and nodes are relevant for the analysis. In high performance computing (HPC) several bottlenecks are anticipated as nodes try to connect with one another including bus latency, bus length in some cases, and the smaller scale of any circuity delays on the processor. The ability to scale or divide the signal without losing the signal across several pathways is also relevant. For the purpose of their analysis, these authors use one of the estimated numbers of neurons in the brain (2 x 1011). The authors use a figure of 1.8-3.2 x 1014 synapses. Division yields synaptic connections for each neuron at 3,600-6,400.

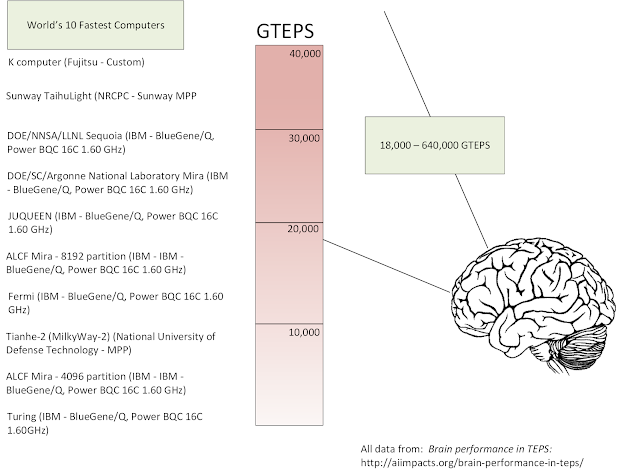

The TEPS benchmark is discussed in detail on the Graph 500 web site under 8.2 Performance Metrics (TEPS). Reference 1 contains a more basic accessible definition as the "time required to perform a breadth first search of a large random graph requiring propagating information across every edge of the graph." The information propagation is between nodes or nodes and memory locations. The Graph 500 site also contains a listing of top performing supercomputer system and a description of their total number of processors and cores. The rankings are all in billions of TEPS or GTEPS in terms of the performance benchmark with 216 systems ranked ranging from 0.0214748 to 38621.4 GTEPS.

For the human brain calculation, the authors use the conversion of TEPS = synapse-spikes/second = number of synapses in the brain x average spikes/second in neurons = 1.8-3.2 x 1014 x 0.1-2 = 0.18 - 6.4 x 1014 TEPS or 18 - 640 trillion TEPS.

What are the implications of these calculations? If accurate, they do illustrate that human brain performance is limited by node to node communication like computers. The AI researchers are not physicians, but it it obvious that taking more nodes or buses off line will progressively impact the computational aspects of the human brain. We already know that happens at the microscopic level with progressive brain diseases and at the functional level with processes that directly affect brain metabolism but leave the neurons and synapses intact. The original research in this area with early estimates was performed by researchers interested specifically in when computers would get to the computational level of the human brain. Several of these researchers discuss the implications of this level of artificial intelligence and what it implies for the future.

For the purpose of my neurobiology lecture, my emphasis in on the fact that most people don't know that they have such a robust computational device in their head. We tend to think that a robust memory is the mark of computation performance and ignore the fact that is why humans can match patterns faster than computers and comprehend context faster than computers. We also have a green model that is more cost effective.

These are all great reasons for taking care of it.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

References:

1: AI Impacts: Brain performance in TEPS: http://aiimpacts.org/brain-performance-in-teps/

2: AI Impacts: Human level hardware: http://aiimpacts.org/category/ai-timelines/hardware-and-ai-timelines/human-level-hardware/

3: AI Impacts: Brain Performance in FLOPS: http://aiimpacts.org/brain-performance-in-flops/

4: Rieke F, Warland D, de Ruyter van Steveninck, Bialek W. Spikes: Exploring the neural code. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA 1997, 395 pp.

Attribution:

Slides below are from my original 1997 presentation (scanned from Ektachrome). Click to enlarge any slide. I am currently working on a better slide to incorporate the work of the AI Impacts and Graph 500 groups on a single slide with an additional explanatory slide.

Additional reference:

My copy of Spikes:

Thoroughly Read: