I have been a serious cyclist for longer than I have been a psychiatrist. At midnight on Labor Day in 1972, two friends and I took off on a trip that we hoped to accomplish the same day. I was riding a CCM 10-speed bike built around Reynolds chromoly tubing. We were traveling to a town 164 miles away. My first friend dropped out at 57 miles. The second made it all the way but for the last third of the trip he was falling asleep on his bike. That trip and several others taught me valuable lessons about cycling. The picture at the top of this post is me stepping off the bike after my initial test cruise yesterday. When I was slightly younger, I would have been out biking as soon as the snow melted. Less than 5 years ago I was out biking down the Gateway Trail on a mountain bike and I hit a patch of ice and went down hard.

As I was dusting myself off, I recalled a story from a gastroenterology colleague of mine who is about 10 years older than me. He would always ride in the

Minnesota Ironman, a spring ride that is designed to be a century (100 mile) ride but also can be broken up to shorter rides. It is scheduled this year for April 26th, with options to ride 14, 27, 29, 60, and 100 miles. The problem in Minnesota at this time of the year is the weather. My GI colleague told me he was sitting there waiting for the ride to start. It started to rain and sleet. By starting time, he was soaked, cold and his shoes were full of ice cold water. He got off the bike, walked over to the van that would be at the finish line with T-shirts, picked up his T-shirt, and went home. I guess the lesson there is that at some point, you realize that you can enjoy cycling and not be miserable doing it. It is a lot easier to ignore misery when you are younger.

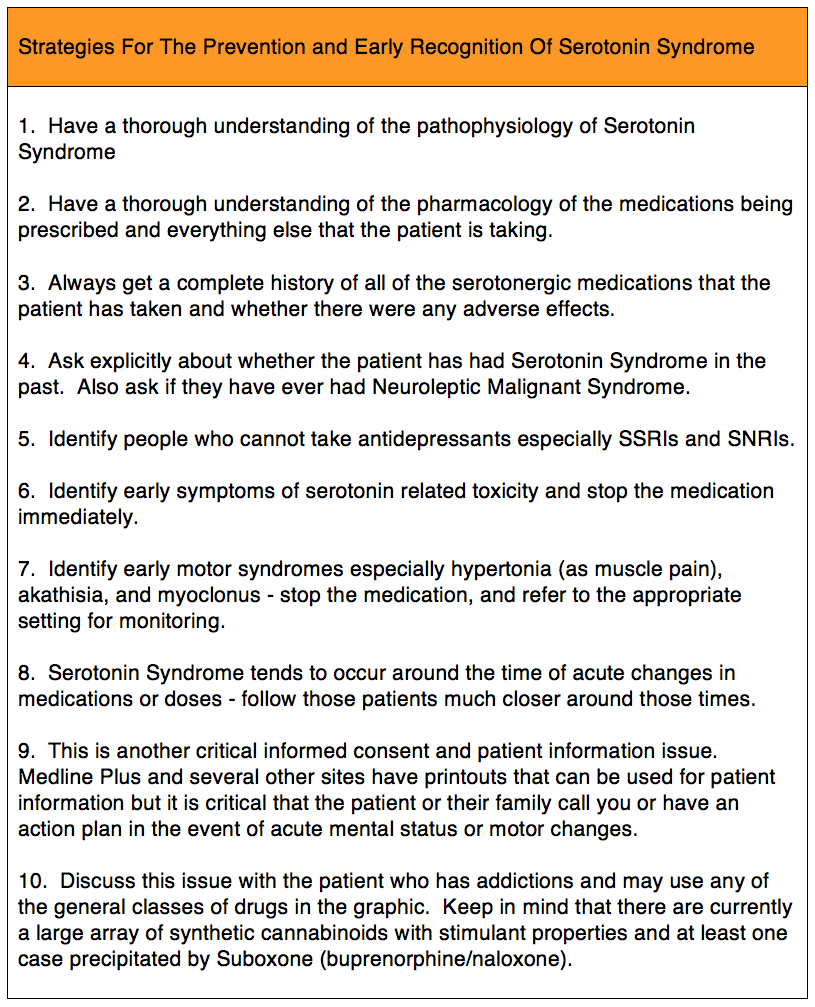

When you are younger, your physiology is also a lot better. I was doing pretty well until about 7 years ago when I had an episode of atrial fibrillation. By pretty well, I mean essentially unlimited exercise potential. I could go as hard as I wanted for as long as I wanted up until that point and even after that point for a while. But eventually I realized that even

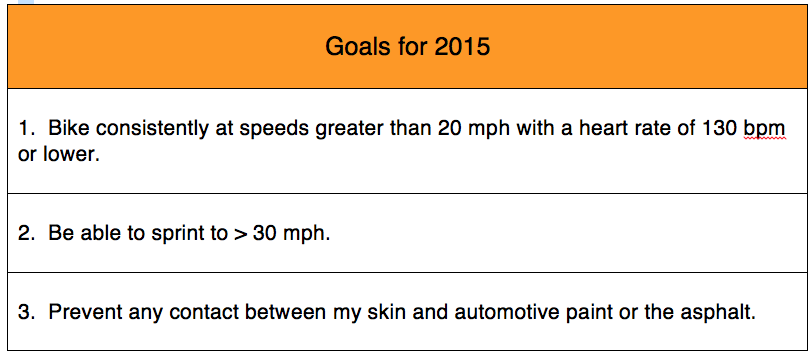

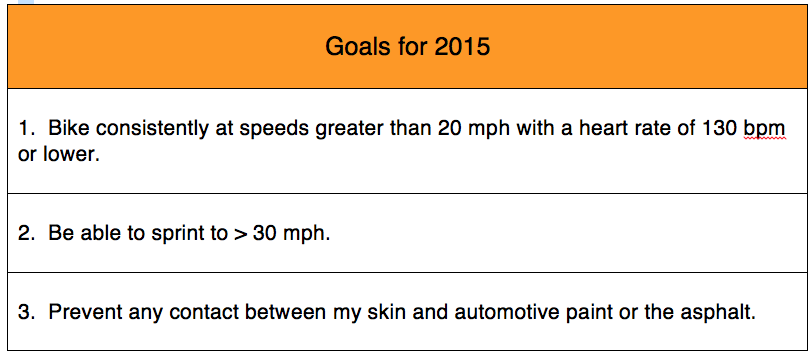

exercise induced tachycardia predisposes a person to atrial fibrillation. I had to tone my very high heart rates down into a more conservative range in order to prevent episodes of atrial fibrillation and the conditions that predispose to atrial fibrillation. Now when I am out in the country, I am always watching a heart rate monitor instead of my speed. That is somewhat depressing and it has an impact on self image when you have to go from unlimited exercise capacity to somewhere on the deterioration spectrum. My goals have varied over the past 30 years from biking 200-250 miles per week to doing more speedwork for racing. My fastest race time occurred when I would do 2 - 50 mile rides on the weekend and 4-18 miles rides during the week. For half of the 18 milers I would try to ride as fast as I could. These days my goals are a lot more conservative and these are my modest goals for 2015.

That may be a little optimistic but for comparison I watched Fabian Cancellara lead the peleton at what appeared to be a leisurely pace into a small French town a few years ago. They were doing 30 mph on the flat and his heart rate was 130 bpm.

I thought that I would share a few observations here about some other things I have learned over the years about cycling that might be useful.

1. Use good gear and keep it in good working order:

The kind of bike you ride is highly subjective. When I first started cycling, high end bikes could only be assembled from components. I used to ride

Vitus frames that were aluminum tubes that were glued together. The mechanical components were made by Campagnolo, Shimano, and SunTour in various prices ranges. My all time favorite components were SunTour

Superbe Pro. They seemed so light and effortless. I just liked the way the gears changed. It seemed like there was just a lot less rolling resistance. But SunTour just went out of business one day. I currently ride a

Trek bike with a carbon fiber frame after riding aluminum frames for over 20 years. Bikes today are so much better in just about every way than they used to. If you bike a lot, it pays to ride the best bike that you can afford and go to a shop where people can explain it to you and fit you to the bike. Don't ride a bike that gives you consistent pain in any part of your body. You should always feel stretched out and ready to go. Don't hesitate to buy a bike that you think looks cool. Don't hesitate to buy as many bikes as you want. These are both strong motivators for riding.

2. Be safe and stay alive:

Biking is in many ways like getting into an open

Land Rover and driving out into the Serengeti among the predators and large animals. Anything can happen and you have minimal protection. Just pulling out of my driveway I always double check the air pressure (it should always be at the max) and I make sure my front wheel is not ready to fall off by pounding on it with my fist. I am riding high pressure tires with tire liners to prevent a blowout. I don't have time to fix flats out on the road.

And then I become hypervigilant......

I was screaming down a hill in Duluth one day and all it took was a split second for a large black Labrador to run out of a bush and right under my front tire. Hitting that dog was like hitting a tree stump at that speed and I went right over the handle bars and onto the shoulder. I personally know too many cyclists who were killed or became quadriplegic in accidents like this. It is the main reason I continue to do a lot of upper body strength training to provide some elasticity in the event of a crash.

In another close call, I was heading south on Cty Hwy 15 from Square Lake Trail just north fo Stillwater, Minnesota. Washington County has the highest per capita income of any county in Minnesota and that is reflected in the state of their roads and what happens to the roads at the county line (they get worse). It is the ultimate biking territory because most of the roads have 5 - 10 feet of pavement to the right side of the white line. That is a lot of biking space compared to most county highways. Coming north in the other lane was a truck pulling a boat on a trailer. I heard some scraping and saw some sparks. Suddenly the boat and trailer reared up, disengaged from the back of the truck and was headed right at me. It cut in front of me by about 5 feet. I think I was saved by the ultra-wide shoulders in Washington County.

I always stay to the right hand side of the while line by as wide a margin as I can. All it takes is this little experiment to prove to yourself that this is the best place to ride. Count the number of cars out a hundred that you see crossing that line in proximity to you when you are riding. The number I get is about 6% and that is when they see that you happen to be riding next to them. Hopefully the new car designs with

lane deviation alerts will train people to stay in the driving lane. But it is going to be a long time before everybody has them and let's face it some of those drivers may be intoxicated even in the light of day.

3. Stay as competitive as you want to be:

I was never a big time racer. I rode only in an annual unsanctioned 40 mile event. It was kind of a free-for-all and it was pretty dangerous. It was a pack style race but in the end, some of the riders were using aero handlebars (ouch) and there was always a massive crash at about the ten mile mark. Some of the riders were Cat 2 and rode in it for practice.

I can recall reading Greg Lemond's book about the attitude to have as you get older - basically that you have more responsibilities and more time commitments away from cycling. That is also true. Ever since I left Madison, Wisconsin in 1986 - I have been a solo biker. The only exception was a play date that my wife arranged. He was a tri-athlete and the husband of one of her health club friends. The plan was to do a 60 miler from Mahtomedi to the Chemolite plant in Hastings back up to Square Lake Park via Stillwater and back to Mahtomedi. This guy took off like he was time trialling and I did not catch him until the 20 mile mark. By then he had hit a wall and his speed started to fall of precipitously. The last third of the way he was down into the 10 mph range and eventually fell off his bike and fractured his wrist. The last few miles into Stillwater I was riding next to him trying convince him to stop so that I could call his wife and get him picked up.

That incident captures some of the problems of biking with other people. What are the mutual expectations? If it is some kind of competition is it at least a benign competition? The skill level has to be in the same ballpark as well as the overall expectations of the ride.

What about people that you encounter along the way? During my time of unlimited exercise, my rule was not to be passed (within reason). I would also try to catch anyone on the horizon, but to do it in the most unassuming manner possible. As aging has taken its toll I have to pick my battles. Two years ago I was out biking towards an average sized hill when I noticed a pack of about 8 guys quite a bit younger than me closing fast. I naturally assumed that their social brain worked like mine and they were trying to trounce the old man going up the hill. By this time I was trying to stick to my heart rate rule of not exceeding 130 bpm and I looked down and I was already at 120 bpm. I increased my speed to match their figuring that some of them were maxed out trying to close the distance. At the bottom of the hill I shifted to a bigger gear and hit it as hard as I could. The group caught me halfway up the hill and then seriously faded. I was the first guy up and over the top. I won't tell you what my heart rate was at the time. I was somewhat elated, especially when the last rider in that group looked over at me and said sarcastically: "Nice work Lance".

Some people view competitiveness as either a character flaw or the most desired personality characteristic. I see it as neither. To me it is the embodiment of training and study in the field as well as the third dimension of how long you can put off the ultimate deterioration of your body. When I win these little competitions that I devise for myself, it is not about the anonymous opponents who I will never know. It is a battle against my own death anxiety and mortality and a good way to stay physically fit in the process.

4. Drivers are either not paying attention or they are trying to kill you:

If you bike long enough or even pay attention to the newspapers, cyclists are always getting killed. Seven hundred and thirty two cyclists are killed every year and 49,000 injured, but it is possible that the police only record about 10% of the injuries. In my town it is about 1-2 people per year. That suggests to me that the fatality estimate is also too low. I personally know both experienced and inexperienced cyclists who were killed and seriously injured. In one of the most noted cases a driver mowed down three cyclists while trying to adjust her CD player. The only defense against the inattentive and/or drunk driver is to be as far to the right of the lane marker as possible and try to avoid sharing the actual traffic lane whenever possible. There are some additional helpful approaches.

Avoid riding in traffic until you know what you are doing. The basic skill requirement is to be able to bike in a straight line and not veer all over the road. That seems easy but it is not. Any type of distraction including talking with your fellow riders and looking over your left shoulder can cause you to drift into the traffic lane. Don't ride in traffic if you are drifting all over the road for any reason. Don't ride in traffic until you can glance over your left shoulder and not drift into the traffic lane. If you know you can't do that - stop the bike completely, put your feet on the ground and look behind you.

Bike with people you know and trust. If you are biking distances at speed you have to know that the person in front of you is not going to pull up all of a sudden without warning and cause a crash or lead you to veer into the traffic lane. Ride single file most of the time, except where you have enough shoulder surface to comfortably ride side by side. You should have enough confidence in your fellow riders that you know they will not make any contact with you.

In some cases, the nature of the ride is just plain dangerous. I can recall riding out of Aspen to

Independence Pass. The shoulder on that road gets down to 6 inches wide as it winds up to the pass. The day that I did it, there was constant

Airstream trailer traffic. The vehicles pulling those trailers were all outfitted with very long side view mirrors to see around the trailers and they were dangerously close. To make matters worse, I was aware of a cyclist who was hit from behind by one of these mirrors. That image of a mirror imprint on my back made the ride up a lot less enjoyable than it should have been. Sometimes your cycling goals take you into dangerous territory in spite of everything you know about safety.

Aggressive drivers are an entirely different problem. They come in several classes that I would described as the appropriately angry driver, the enraged driver and the personality disordered driver. There is a significant overlap between the personality disordered driver and the enraged driver and that depends on the assumption that a person can have defects in emotional reasoning in the absence of major character pathology. As far as I know that study has not been done. Prevention is always the best initial approach and by that I mean not doing anything to piss drivers off. It does not take much. After all they are in a two ton vehicle obligated to adhere to the rules of the road or risk legal penalties and suddenly the cyclist in the oncoming lane buzzes right through a stop sign. That action is enough to cause the mild-mannered banker who you personally know to start pounding his steering wheel with both hands while screaming epithets out the window (Don't ask me how I know that). Simply put you will anger fewer drivers by adhering to the same rules that they have to. That will not prevent all angry encounters because there remains some ignorance about traffic laws. For several weeks I encountered an angry young woman cycling toward me in the wrong direction on my side of the road. She was riding against the traffic. She was aggressively swearing at me and telling me I was going the wrong way until I politely told her to read the drivers manual.

But obeying all of the traffic laws will not keep you out of the cross hairs of our various personality disordered citizens. I was biking up Myrtle Street in Stillwater, MN one day. It is quite a haul and most road bikes don't come with small enough chainrings to make it up that hill very comfortably. I was 2/3 of the way up when suddenly a young man in a large 4WD pick up truck (not that there is anything wrong with that) pulled up next to me and started to harass me all of the way to the top. His basic heckle with the expletives removed was: "Yeah you're not so tough now are you?" Wait a minute, I am the 55 year old guy riding up this hill on a bike and you are the thirty something guy sitting in a 400 horsepower truck going up the same hill and I'm not so tough? Harassment like that can be disorienting, I flipped into my mindfulness mode and thought about all of the times I have biked this hill - while keeping an eye on how close the truck was to me.

In a previous incident, I was at the bottom of this hill when an elderly driver decided to turn right into me as we came up to the third or fourth cross street. Luckily she was going at a low rate of speed and I was at the right place where I could slam my hand down on the roof of her car and spin myself and the bike out of the way. She was oblivious to the whole situation and kept driving.

One of the worst things that you can do with the enraged or personality disordered driver is to escalate the encounter. It took me a while to figure this out. The best example I can think of involves being harassed by a motorcycle club on day toward the end of my ride. I doubt that they were 1%ers, but they were all young very muscly guys wearing sleeveless motorcycle jackets and seeming quite intoxicated. As I rode by one of them had climbed the cyclone fence that surrounded this establishment and started to shout "Wheelie! Wheelie! Wheelie!......" as I pulled up to a stop sign. Several of his peers caught wind of this and started to do the same thing. It was a scene out of a biker film from the 1970s. Clearly they were expecting a response from me. In the old days, I might have said something and it would have been off to the races. Today the exchange went something like this:

Me: "I can't do a wheelie."

Intoxicated Biker: "Why not?" (angry tone)

Me: "Because I am too old!"

Intoxicated Bikers: Explode into laughter. As I ride away they are reassuring me that I am not too old to do wheelies.

So the bottom line is that some of these ugly confrontations can be defused with humor.

5. Fantasize your brains out:

Psychiatrists don't talk about fantasies any more. I think that an active fantasy life can be very adaptive. I have fantasies that I can pull up in any terrain. In the hills or mountains I can imagine myself riding between the Schleck brothers in the Alps. On level ground or into the wind, I can see Miguel Indurain time trialling in front of me and I am just trying to maintain the correct spacing between us until I can pull out and pass him. The weeks of the

Tour de France are generally the times of peak fantasy for me. There is always the case of a solo rider who breaks away from the best cyclists in the world and stays away. I can't think of anything as exciting in all of sports. I am waiting to watch that clip and incorporate it into my fantasy world. I can hear Phil Liggett calling out my name.....

6. The cognitive versus the emotional aspects of life:

I have decades worth of meticulously detailed training information - all handwritten. Distances and times, routes, intervals, heart rates, etc. In the 21st century, none of that stuff is necessary. You can automatically record all of that data and download it to your computer after the ride. You can study whatever parameters that you want. But don't get too lost in the details. I live for the time during the year when I am cruising along in a fairly steep gear and can put my foot down and

go.

Bam! I am sure that any coronal section of my brain on fMRI at that point would show my nucleus accumbens lighting up, but the subjective experience is most pleasurable. It can occur only with the right distribution of power and weight and I notice that it is advanced on in the season. If it ever disappears, I know that I will miss it.

7. Wear the most radical clothing you feel comfortable with:

Most non-cyclists don't understand the utilitarian nature of cycling clothing. I was speedskating one night and came off the ice with some biking gear on. One of the hockey dads decided to give me a rough time and commented how I must think that I was pretty cool because I had special speedskating clothing on. Keeping in mind that he had several kids with about a thousand dollars worth of hockey gear on, I said: "Well no, this is my cycling clothing." On top of thermal underwear of course.

I have been in pursuit of the perfect biking shorts and saddle for the past 30 years. When I find a pair that seems to meet the criteria, it doesn't take long for the manufacturer to change the design or the chamois. It is a basic fact that you cannot expect to bike every day if your perineum is trashed or you develop saddle sores. The best way to do that is to think that you are going to ride more than 10 miles in a pair of cotton Bermuda shorts over boxers. I am currently trying out some very high tech shorts. They were so high tech that I had to send an e-mail to the company. I was concerned about what kind of chamois lubricant to use, because of all of the high tech materials used in the short. Their reply was totally unexpected. Don't use anything. Wear these trunks dry. So for the first time in 30 years I don't have some kind of lubricant between my ischial tuberosities and my bike saddle.

Live and learn.

8. Inclement weather:

I don't bike in the rain or snow anymore. I will also not be biking up to

Independence Pass again unless they ban Airstream trailers. I have an

ergometer in my basement and I try to match the outdoor conditions. I know that at many levels that is an illusion. I do however always bike in extremely hot weather and in the wind. It takes a certain mindset to overcome those conditions. You have to be able to feel that you are going with the wind and benefitting from the temperature at some level.

This is a long post and that's all I can think of for now. So the next time you see some old dude out on the road biking - he may be a narcissist wrapped in Lycra, but it is more likely he has a lot on his mind and he is trying to live the best way that he can.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

Supplementary 1:

Disclaimer: I am not a cycling coach or expert. The point of this post was to look at some of the unspoken psychological aspects of biking from the standpoint of individual consciousness. Don't take any of this as advice on how to cycle or live your life. Follow the advice of your personal physician on all matters related to exercise especially if you have decided to start a new program or alter your intensity.

Supplementary 2:

I am a guy so this is written from a male perspective. I know that women are as dedicated and serious about biking as I am, but I can't speak to their conscious state. If you are a female cyclist feel free to comment about your conscious state in the comment section below. Or better yet, send me an essay and I will post it as an invited commentary by a distinguished guest. I am very interested in your motivations, cycling fantasies, and daydreams about cycling and any insights that you have developed as a result. Not everyone can keep riding and I am very interested in the ways that people do.