In the 1960's a condition called Quebec beer drinker's

cardiomyopathy was described in the medical literature. Between August 1965 and April 1966 46 men and 2 women were admitted to 8 hospitals in Quebec with acute cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure. Twenty of them died. During the epidemiological analysis it was determined that they were all heavy beer drinkers. An extensive analysis of the this phenomena is available in full text at the initial link on this page. For those of us trained through the end of the 20th century the clinical methods in the 1960s were not that far removed. The mystery was solved then by a combination of epidemiology and pathology:

"Suspicion of cobalt as the toxic agent was aroused after examination of the thyroid glands removed at autopsy showed changes similar to those found in cobalt intoxication. Had cobalt been added to the beer? Yes"

Similar patterns had been observed in Minneapolis, Omaha, and Louvain (Belgium). Why am I suddenly interested? The

New England Journal of Medicine Clinical Problem-Solving case of the week entitled "Missing Elements of the History." In this case a 59-year old women who was previously in good health develops acute congestive heart failure and a cardiomyopathy is diagnosed. She has a complicated course with an initial pericardial effusion. After acute treatment no etiology of the cardiomyopathy was determined and she was assessed for heart transplantation. Her heart failure worsened and she developed cardiogenic shock and needed a left ventricular assist device. Three months later she received a heart transplantation and was discharged home in 20 days.

Was the patient in question a drinker of cobalt laced beer? No - but she did have cobalt in her body. She had bilateral DuPuy ASR metal-on-metal hip prostheses that had been placed 5 years and 4 years prior to the heart transplant. She had learned about one year prior to transplantation that the prostheses were being recalled due to a higher than expected failure rate and a protocol for follow up was sent to her. She was advised to get repeat hip imaging and serum cobalt levels done. Pelvic MRI showed reactive areas with fluid collection and the cobalt level was elevated at 287.6 mcg/liter with a reference value of less than 1.0 mcg/liter. The prostheses were removed 11 and 13 months post heart transplantation. She had a complicated course but apparently recovered. Serial cobalt levels were done and 16 months after transplantation remained at 11.8 mcg/liter a significant drop. She also had a chromium level determined at 248.9 mcg/liter about 8 months after transplantation.

The NEJM article points out that about 1 million people had these prostheses implanted between 2003 and 2010. The authors here strike me as being overly modest in saying that they cannot absolutely confirm that this is a case of cobalt induced cardiomyopathy, but there is just too much evidence to hedge around. Read their timeline of events in Table 1. and see what you think. It would certainly seem to have implications for regulatory bodies like the FDA. The parallel regulatory body in the UK states that any patient there needs lifetime annual follow up including imaging and blood cobalt and chromium levels. The FDA

recommendations are much more nonspecific and they appear to be placing the monitoring burden on primary care physicians and other specialists.

What does the New York Times report about this story? They have a story in November 2013 about $2.5 - 3 billion being award to a group of about 8,000 patients in the US. They have another story that the manufacturer seemed to know earlier about the high than expected failure rate and need for replacement. In that

same story they quote the total number of recipients as "93,000 people, about one-third of them in the United States" as opposed to the NEJM estimate of 1 million people world wide. Most of the stories I could find (15 of 26) were in the business section. There is an interesting quote near the end of the article about how taking it off the American market was strictly a business decision. In other articles there is a hint of a cover up and a hint of doctors not speaking up to warn other doctors, but the story has been out there since March 2010. Where is the outrage?

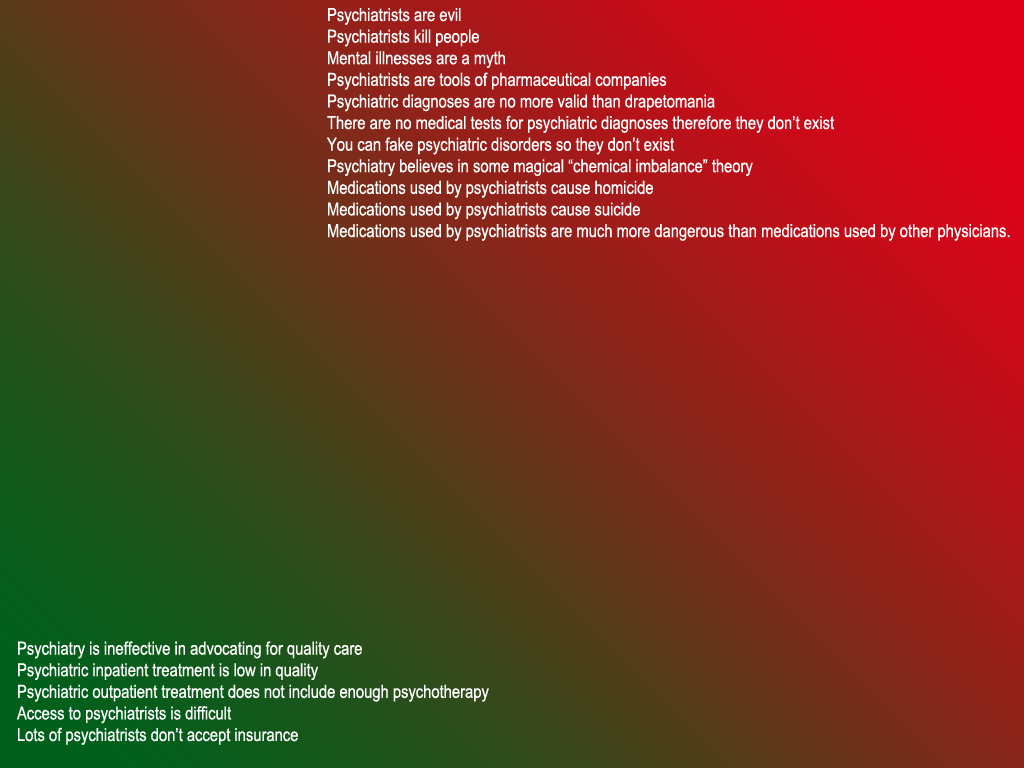

We have just gone through a several year period of bashing psychiatrists for daring to rewrite a diagnostic manual that they use by themselves. Further that manual explicitly says that you really can't just read the manual. You need to be trained in medicine and psychiatry first. There was plenty of outrage then. Critics of all types in the New York media writing an endless stream of negatives about psychiatry and the DSM-5. Accusations of conflict of interest (more appropriately the appearance of conflict of interest). Outrage over various parties not being to have enough input into the book (when in fact the web site designed for that purpose took in thousands of comments that were debated by the work groups). Outrage over whether the manual was written to appease the pharmaceutical industry that

ignored the basic facts. I could certainly go on, but what is the point? Everyone has heard these stories. They are commonplace.

The DSM-5 came out and nothing happened. Clinical psychiatrists did not blink an eye or make any major changes. Nobody ended up with elevated cobalt or chromium levels. Nobody ended up with needing more surgery or congestive heart failure from cardiomyopathy. I certainly do not want to minimize what all of these hip implant patients are going through but it seems that the press and the FDA are doing just that. I think the lesson is certainly there when you look at how the media overreacts to psychiatry they end up appearing to be very tolerant of significant problems in other fields of medicine.

My suggestion for the psychiatry critical press is that it might actually be worthwhile to critique other branches of medicine where there are significant problems. Hold them up to the standard that you apply to psychiatry and see what happens.

If you can't there is clearly something wrong. At the minimum I propose that outrage should be proportional to a real problem rather than the appearance of a problem. Or better yet - it could just disappear and be replaced by a more rational analysis.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

Allen LA, Ambradekar AV, Devaraj KM, Maleszewski JJ, Wolfel EE. Missing elements of the history. N Engl J Med 2014: 320(6): 559-566.

Siegel E, Lautenbach AF.

Determination of cobalt in beer. Siebel Institute of Technology and World Brewing Academy.

Interesting historical document on why cobalt may be added to beer including the fact that the FDA apparently approved this application in 1963.

Clinical Note 1: I added this for the clinical psychiatrists out there who I know see a large number of people with hip implants. Be on the lookout for pain, lack of follow up with their surgeon or signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure. The

FDA warning also suggests depression and cognitive changes.

MedlinePlus also has patient handouts. It probably is also a good idea to remember that some people may be taking cobalt and/or chromium ionic forms as a supplement. As an example poor quality information that can be seen on the Internet, there is some information on the that cobalt boosts erythropoetin (EPO) and athletic performance that is based on animal studies from the 1950s. Trying that would obviously be an extremely bad idea. A history of use of supplements is important for these reasons.