"Exacerbation of both COPD and asthma, which are basically defined and diagnosed by clinical symptoms, is associated with a rapid decline in lung function and increased mortality." -

Frontiers in Microbiology October 1, 2013.

For starters this is a lengthy and somewhat obsessive look at a personal episode of illness and the implications it has for some of the common threads on this blog ( overidealization of general medicine, dislike of psychiatry, inaccurate comparisons of psychiatry to the rest of medicine, wild criticism of psychiatry, etc.). So if you are not into that - this would be a good place to stop and move on...........

I have been off work 9 out of the past 10 days with an upper respiratory infection leading to an exacerbation of asthma. At least that is one theory. I first noticed it when I stepped off my ergometer trainer about 2 weeks ago and noticed that I did not seem to be able to take a deep breath and I was wheezing mildly. I saw an Internist the next day who did a history and examination and got a chest x-ray and an electrocardiogram - both of which were normal. She decided to double the dose of a corticosteroid inhaler that I was using and told me to increase double the dose of the albuterol inhaler I was using. She said she would not add oral prednisone at this point. When I got home I realized that my corticosteroid inhaler was empty and I needed a new one. The office was contacted and sent a prescription for the previous dose rather than the new dose. When I called and asked them to read the documentation, the note mentioned an even higher dose that was not possible with the inhaler I was using. The inhaler cost $187 for one month so I figured it was easier just to start using it rather than wait for them to sort of all of the communication problems, especially because the physician was not available for another several days and I was still wheezing.

Two days passed and my breathing seemed slightly better so I went into work. By mid afternoon the inability to take in a deep breath came back and I went to an Urgent Care clinic through my health plan right after work. The new doctor repeated the history, physical, and chest x-ray (again negative). He prescribed a more intensive course of therapy with a 12 day prednisone taper starting at 60 mg/day and a nebulizer machine with ampules of 2.5 mg albuterol. He told me to keep taking both inhalers and add both of these. When I got home I took the prednisone and assembled and used the nebulizer.

I will digress to say that I am a firm believer in the absolute need to control blood pressure and pulse. I measure my blood pressure and pulse four times a day or more depending on the circumstances. White coat hypertension probably happens but how many people know what their blood pressure is once they get back home? I know from personal experience that a hostile work environment can drive both your pulse and blood pressure through the roof not just for days but for weeks to months. The only time I am comfortable being hypertensive is when I am exercising because it it physiological, I have been monitored doing it by

sports physiologists and they were happy with it, and I know there is a compensatory post exercise response that controls BP and pulse in the long run. I take what most physicians agree is a homeopathic amount of antihypertensive but my BP is never greater than the

CDC recommended cut off blood pressure of 120/80. It is usually 10 points less. That belief comes from seeing many people over the years who had decades of untreated hypertension that either they or their physician seemed to attribute to something else. Psychiatrists are occasionally in the situation of treating patients with extremely high blood pressures like greater than 200 systolic and 120 diastolic who refuse treatment. They are usually being seen by psychiatrists because of the need to get a court order for them to be treated and that often takes several weeks, putting the patient at risk all the while. I have seen the full spectrum of blood pressure related problems and there is only one logical conclusion that blood pressure needs to be well controlled.

I am also a student of respiratory viruses and a veteran of two different avian influenza task forces. The task force experience left me quite pessimistic about our ability to fight off any actual pandemic for a reason that is quite striking - the denial that there is an airborne route of infection. Everyone on the task force was focused on hand washing and controlling fomites and there was very little focus on what was needed to contain airborne infections, probably because we learned that capacity would be overwhelmed on the first day of the pandemic. At that point we are basically in a slightly better position than we were in the

influenza epidemic of 1918. At one point they showed us a couple of plastic covered pallets of Tamiflu in a government warehouse somewhere. I stopped attending when they started to talk about where the dead bodies would be stored.

But my interest is also in the area of common everyday respiratory viruses. When you are working in a hospital with 1970s era ventilation systems (contain the air to save heat) you witness the staff around you and yourself and the patients get ill in mini-epidemics 3 - 4 times a year. All with the same symptoms of varying severity. Some will end up on antibiotics and some will end up on Medrol dose packs or both. It happens whether you wash your hands or not. At some point I started to e-mail the Minnesota Department of Health and inquire about the respiratory surveillance of flu and flu like illness. At some point they got tired of my email and

put it all online. The bottom panels show (with a lag time) the likely viral culprits based on various identification methods. Rhinovirus and adenovirus are among the usual suspects. Reading my copy of

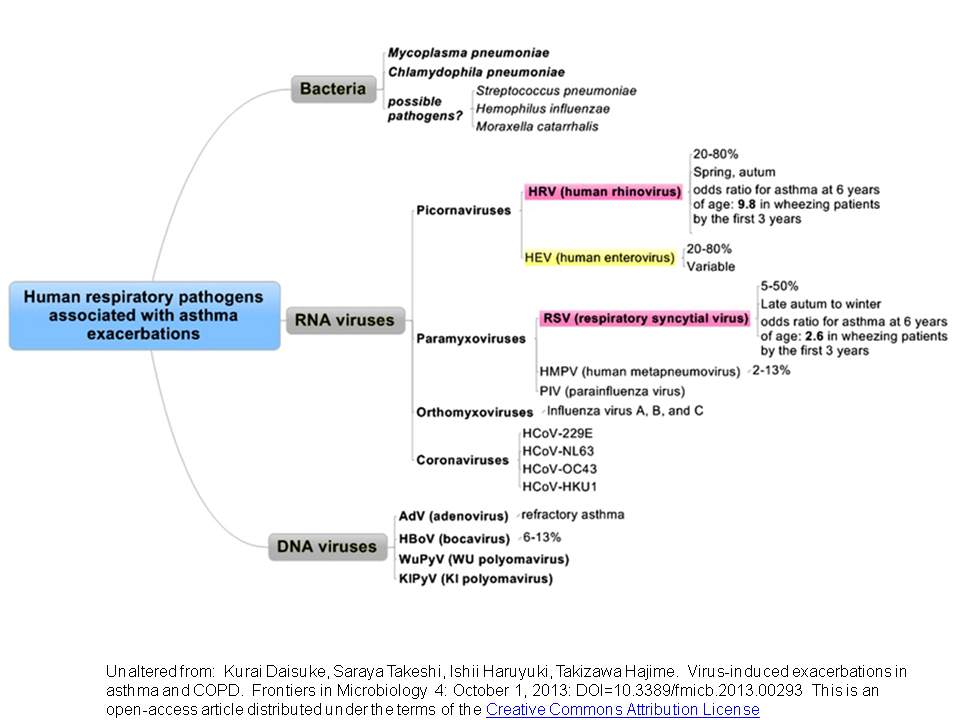

Gorbach, Bartlett and Blacklow confirms the syndromes.These are the kinds of trends I would see every year. I consulted with a top expert in airborne viruses in building. He had done the first studies to confirm that viruses can be sampled in the airflow of buildings and that they are typically airborne viruses. For two years, I studied the airflow and filtering characteristics of buildings and how older ventilation systems might be modifiable to reduce the risk of respiratory infect by airborne viruses. I looked at the specific air flow characteristics of the building I worked in. I surveyed the employees on each unit showing a high clustering of upper respiratory infections and and flu like illnesses. During that entire time I got numerous respiratory infections with no exacerbations of asthma, but according to the following graphic - it was just a matter of time (

click to enlarge):

After the initial nebulizer treatment my systolic and diastolic blood pressure was up about 30% and I was feeling somewhat agitated and anxious. I had only had one nebulizer treatment in my life and it was about 20 years ago. I looked at the doses and found the inhaler contained 180 mcg of albuterol compared to the 2.5 mg in the nebulizer with greater bioavailability. In other words the nebulizer delivered 14 times the dose and I was told to use it up to 6 times a day. I slept about 2 hours that night.

The next day I ran a drug interaction search on my revised list of medications and several potential drug interactions were noted - a couple of them significant. I logged into my health plan and sent my personal Internist a note with several question on the interactions with drugs and my existing medical morbidities. He called me up concerned that I might have the flu, but I had just seen him and been referred for an extensive immunology evaluation for the flu shot and got it. I told him about my experience with the nebulizer and he chuckled: "In the ER they might give you this very 1 - 2 hours but of course you are hooked up to a monitor and they are checking your blood every hour." At this point I have not had a single blood test. He suggested that I try a new inhaler - levalbuterol and the equivalent nebulizers. They were supposed to have fewer side effects. I spaced the treatments out exactly 8 hours and five minutes after the third treatment my heart rate shot up to 140 beats per minute and a blood pressure of 147/103. I took some medication that I knew would bring it down in about 45 minutes, but also prepared to call 911 if it continued to climb. Gradually over the course of 30 minutes my blood pressure and pulse recovered.

So what can be concluded by my latest foray into the healthcare system?

1. Medical knowledge may not lead to any improvements. As far as I can tell nobody is very receptive to the idea that respiratory viruses exist and that while hand washing is helpful it will not necessarily protect you against some of the worst viruses. The unreceptive parties occur at all administrative levels and seem content with watching employees get recurrent viral infections and use their paid time off. Is that a form of cost shifting?

2. Syndromal diagnoses are alive and well in medicine and not just psychiatry. I have talked with 4 physicians during this week long bout of illness and none of them have a clear diagnosis other than an exacerbation of asthma. The asthma we are talking about is not a specific type or subtype that may have implications for treatment - but the good old heterogeneous type. As heterogeneous as just about every known psychiatric diagnosis. The first physician thought the likely cause was dry winter air. By the time I had seen the second physician I had some additional symptoms to suggest a URI. Only my personal physician seemed concerned that I may have influenza and called me back a second day to make sure that I had not developed a fever. I had vital signs determined, peak flow meters, oxygen saturations, 2 chest x-rays and an electrocardiogram. None of the tests was a biological test for asthma or whether there was an underlying infectious agent. None of the tests were positive or could quantitate my illness. Recall that a typical argument rolled out about psychiatric diagnoses is that there is no specific test and that they are all syndromes. I learned that clinics in my health care system no longer do the rapid test for influenza because it is not considered to be accurate. In all cases I was being treated based on a syndrome and nothing else.

3. Could a more specific diagnosis be worthwhile? Most certainly since there is some evidence that rhinovirus is a common cause of asthma exacerbations and may also be a cause for asthma in childhood. There is also evidence that rhinovirus can replicate its RNA in the lower respiratory tract for up to 16 days post infection. It was only recently discovered that rhinovirus inhabits the lower respiratory tract and can replicate there. The biological test that was done for influenza is no longer used because it was inaccurate, would that be useful to know? I have a previous post here about

asthma endophenotypes. Is there an endophenotype for rhinovirus induced asthma? Is it caused by epigenetic mechanisms? These are all parallel questions that psychiatric researchers are working on right now with most major psychiatric disorders.

4. Cost shifting to the patient is paramount from several sources. I purchased 3 - $200 inhalers in 3 days that were not covered by my insurer. The first one was an error because it would have covered 2 weeks of treatment and it did not match the documentation in the original note. In all three cases the pharmacists warned me about the high cost of the inhaler, but when I asked them if there was a generic substitution they said there was none. The current albuterol inhaler also has no generic apparently because it is the only environmentally friendly one. That is the difference between a $50 copay and a $4 copay. There is also an angle from the perspective of ethical purism and pharmaceutical manufacturers. Is this a case to be made for samples? Should a patient try a sample of the inhaler in their doctor's office to make sure they can tolerate it and know the price before going to the pharmacy? That way there would be an assurance that the patient could tolerate and afford a very expensive medication. I currently have $400 of inhalers that will be used twice and are otherwise worthless to me. The other scenario that is difficult to contemplate is a person being forced to drive away from the pharmacy without a medication due to the surprise cost or copay.

5. There was minimal discussion of side effects and contingencies but scripting was noted. Scripting is a public relations initiative where health care personnel are trained to ask questions that the patient may be asked about in a satisfaction survey. For example at the end of the visit the physician says: "Do you have any additional questions for me today?" A week later you get a survey to rate the physician on whether or not he asked that question. In the meantime no warnings about prednisone or what to do if I got hypertension or tachycardia from the albuterol. I was told that I might expect some palpitations and that might be expected because "there was more medicine in there than from the inhaler". The levoalbuterol was supposed to solve the problem but it resulted in significant tachycardia and I later learned it was pulled from a hospital formulary because it did not "work as advertised". That is the optical isomer did not protect against side effects like tachycardia.

6. Pattern matching is implicit and probably carries the day. I have previously written about the importance of pattern matching in medical diagnosis and it was probably a significant factor in all of my physician encounters. They looked at me and could tell I was not acutely ill - I did not need to go to a hospital. There are various ways of phrasing it but that conclusion was uniform. The pattern matching also probably drives a lot of the questions that flowed from the patterns of asthma exacerbation in their previous patient encounters.

7. Complex medical diagnoses are a process. On this blog I have pointed out why a checklist screening is generally an inadequate approach. There is probably no better example than logging in to your health care system's triage software and realizing that your problem is not listed among the choices. In this case information changed over time from asthma due cold air to asthma due to a viral exacerbation. The treatment was also significantly and expensively changed along the way.

8. Asthma and related conditions are a huge

public health problem. The prevalence of asthma is about 10% in developing countries and it accounts for 1 of every 250 deaths worldwide. Only 1 in 7 people with asthma have it

well controlled. Public health interventions seem like a last resort. Trying to get people interested in the true nature of airborne viruses and how to prevent these cyclical infections is practically impossible as far as I can tell. I have corresponded with the head of the

Cochrane Collaboration section on

Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses who cautioned me that no one knows how URIs spread or how many of the interventions work! Even World Health Organization (

WHO) initiatives seems to leave out the all important aspect of building design and airflow. There seems to be a distinct medical bias when it comes to respiratory infections. The only potentially useful and very cost effective public health interventions that I may have availed myself of are the pneumococcal vaccine polyvalent (Pneumovax) vaccine and the

influenza vaccine.

A related issue is how much epigenetics comes into play, specifically epigenetic modifications that occur to environmental exposure of let's say - rhinovirus. Is it possible that exposure to rhinovirus causes more long term health problems for kids than exposure to cigarette smoke? If that is even possible, why aren't we doing more about it?

9. The elegant hypothetical molecular mechanisms of disease don't translate well to clinical medicine in the case of asthma any more than they do with mental illnesses. Skeptics and critics of psychiatry (most of whom seem to know nothing about molecular biology) frequently use this rhetoric without understanding how little these mechanisms apply in other major diseases. Cytokine signalling alone has been described as "having such staggering complexity that the long term behavior of system is essentially unpredictable." Brain complexity is far greater. The use of prednisone to shut down inflammation is more of a shotgun approach to shutting down inflammation rather than anything to do with disease specificity. Given the fact that

endophenotypes are not actually diagnosed at this point and viral infections often are associated with acute onset of asthma, it would seem that there is not a lot of diagnostic specificity beside the syndromes. There is also the question of the time course of improvement. People have ideas about how quickly medication prescribed by a psychiatrist should take to work. Very few of those ideas are accurate. On the other hand here I am on day 16 of treatment for asthma and I am still ill. Aren't real treatments that are based on elegant biological mechanisms supposed to work faster than that?

In the end I am reminded that psychiatry is no different than the rest of medicine that deals with complex heterogenous conditions. Diagnoses are imprecise, there is a focus on patterns, there are very few pathognomonic or gold standard tests, and the management of side effects of medications is as important as treating the underlying problem - at least in non acute situations. Information transfer between the patient and physician is imperfect and nobody seems to be working on ways to optimize it. If anything the critical time domain is being restricted by businesses and governments. Those same businesses and governments seem completely disinterested in non medical approaches to reducing disease burden like building design. There are plenty of false positives and the best assurance you can get is from a single physician who knows you the best. Despite all of the medical care I have received these past two weeks, I think about all of the decisions I had to make on my own and ask myself: "How do people with no medical training decide what to do in this situation and how do they know what information is relevant?"

It must be mind boggling.

Despite all of the technology and medical knowledge a lot of the information transfer still comes down to what happens between the patient and the doctor. There has to be enough time for that to happen. It has to be meaningful and the patient should know what to do if problems occur.

That is true for doctors of all specialties.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

Supplementary Information 1: The supplementary material here is a graphical primer on allergic asthma and how exacerbations of asthma may occur. Rather than an airborne allergen a respiratory virus triggers the cascade of events that leads to the flare up (top figure). That fact is still only recently being elucidated. For example, rhinovirus is a common initiator and it has only recently been demonstrated that rhinovirus replicates in the lower respiratory tract and that rhinovirus RNA can be present for as long as 16 days. As indicated by the tables that follow, cytokine signalling in asthma is complex. The authors show here it may involve up to 22 separate cytokines. Corticosteroids like prednisone and prednisolone inhibit gene expression via transcription factor NFκB to decrease the activity of cytokines. They also reduce the activity of nitric oxide, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and adhesion molecules by similar effects on on synthesis and decrease lymphocyte activity.

Supplementary Information 2: I have a

post available that looks at the early addition of prednisone, but there is a lot of additional information. The following table is the actual course of treatment that I received from four different physicians (color coded) over the course of two weeks. It is posted here for discussion purposes only and should not in any way be construed as medical advice. The disclaimer for this blog applies in that nothing here is for the purpose of medical treatment or advice.