There was some of the usual controversy in the media today. Is Attention Deficit~Hyperactivity Disorder over diagnosed or underdiagnosed? The usual controversy contained the usual stories of how easy it is to get a diagnosis of ADHD in some places. In some places it seems like just a matter of expense - a thousand dollar test battery. In other places there are people disabled by the condition who cannot get adequate treatment. In the meantime there are international experts cranking out reams of papers on the importance of diagnosing and treating this condition in childhood. Occasionally an article shows up in the papiers about the cardiovascular safety of these medications. And in the New England Journal of Medicine there was a paper about a higher incidence of psychosis due to these medications. Where does the reality lie?

I was fortunate enough to have worked at a substance use treatment center for about 12 years just prior to retiring. Only adults were treated at that facility. A significant number of them were diagnosed and treated as children. There were also a significant number of patients newly diagnosed as adults - some as old adults in their 60s and 70s. Whether or not ADHD can occur as a new diagnosis during adulthood is controversial and establishing a history consistent with childhood ADHD is problematic due to recall errors and biases. Secondary causes of ADHD in adults such as substance use problems and brain injuries increases in prevalence. Although I am speculating, secondary causes seem a more likely cause of attentional symptoms in adults and therefore acquired ADHD without childhood ADHD if it does exist is an entirely different problem.

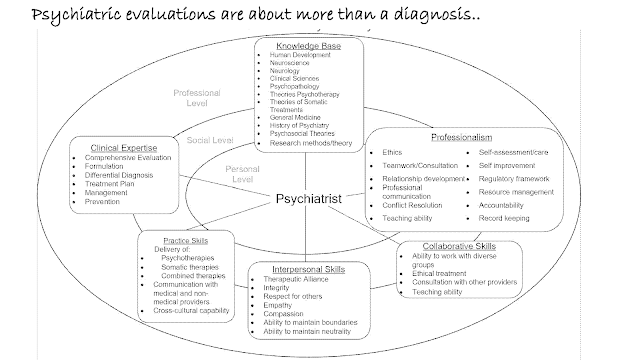

Prescribing stimulants to patients who may have stimulant use disorders is problematic for a number of reasons. Initially we had an administrative safeguard on the practice. Stimulant prescriptions could only be approved with a second opinion by another psychiatrist after reviewing the record. Eventually we had a core of psychiatrists who practiced the same way and the second opinion was no longer necessary. Over the course of 12 years I developed these discussion points. I think they are a good example of the minimum ground you need to cover in an evaluation for ADHD. I typically had a 60-90 minute time frame to work with and could see people on a weekly basis for 30 minute follow ups. These evaluations were often controversial and resulted in collateral contacts, typically with a family member who was advocating for the stimulant prescription.

A few basic points about ADHD and establishing the diagnosis. Like many psychiatric disorders there is no gold standard test. Like some of the media discussions, I have been told that a person underwent days of testing before they were given the diagnosis of ADHD. These are typical paper and pencil tests, but there have also been tests based on watching a computer screen and even crude EEG recordings. There are a few places that use very sophisticated brain imaging techniques. Unfortunately none of these methods can predict a clear diagnosis or safe and effective use of a medication that can reinforce its own use. That leaves clinicians with diagnostic criteria and and a cut off based on functional status as a result of those symptoms. That may not sound like much, but it eliminates a large pool of prospective ADHD patients who have no degree of impairment and those who are obviously interested in possible performance enhancement rather than ADHD treatment. Stimulant medications are highly abusable, as evidenced by several epidemics of use dating as far back as 1929. We are in the midst of a current epidemic. For those reasons it is important not to add to the problem as either the individual or population levels. In my particular case, I was seeing patients who were all carefully screening for substance use and adequate toxicological screening. Since they voluntarily admitted themselves into a treatment center it was also more likely that they recognized the severity of the problem and were more open to treatment. Even against that background - it is worth covering the above points. Covering those points often involves repetition because of cognitive problems in detox or disagreement.These are just a few health and safety considerations. My main concern in this area is that psychiatric treatments somehow have the reputation that they don't require medical attention. They are somehow isolated from the rest of the body. The person prescribing this medication needs to assess the total health status of the individual and determine if the medication prescribed is safe to use. Cardiac and neurological conditions are at the top of that list. I gave a blood pressure example because I have been impressed with how many people tell me that their blood pressure was not checked after a stimulant prescription or a stimulant was started despite diagnoses of uncontrolled hypertension, cardiovascular disease, cardiac arrhythmias or cerebrovascular disease. These were typically new prescriptions in older adults with no prior history of ADHD. Coexisting psychiatric disorders are also problematic. Most have associated cognitive symptoms if they are inadequately treated. That is not a reason to diagnose ADHD or start a stimulant medication. Typical symptoms that can be caused by stimulants are have to be recognized and the medication must be stopped if adjusting the dose is not helpful.It is important to keep the range of biological heterogeneity in mind. Once you have narrowed down a population of people who most likely have ADHD, they will not all have a uniform response to medication. They may not all want to take medication. As adults many stopped taking ADHD medication and adapted to a work and lifestyle that works very well for them. That is a very suitable outcome for an initial assessment. There is another group who want to try a verbal therapy for ADHD in some cases because they recognize they can no longer take stimulants because they were escalating the dose. That is also a suitable outcome for the assessment. In those people who have ADHD are want to take a medication, I think a non-stimulant medication like atomoxetine is a good place to start. In my experience it works very well. Disagreement about stimulants, especially in people with a stimulant use disorder typically requires extended conversations with the patient and their family. A quality control initiative can provide very useful data for that conversation. I suggest that any clinic or clinician who prescribes stimulants collect outcome data on those prescriptions. The key piece of data is a comparison of the relapse rate of those patients taking stimulants compared with patients treated with non-stimulants. Other data could be collected as well - like how long the prescriptions were refilled. There are rules about collecting that data depending on your practice setting. Check those rules first. Outcome data will be the best data on whether a correct decision was made about prescribing the stimulant.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

Photo Credit: Many thanks to my colleague Eduardo A. Colon, MD for allowing me to use his photos.