I quit my job last Thursday night at about 9:30 PM. My term of employment was officially over at

the close of business today – Tuesday January 19, 2021. It happened during an exchange of fairly

terse emails with my immediate supervisors. Those emails occurred in the

context of a flurry of daytime emails that were critical and could easily be

interpreted as making me look as bad as possible. I have no plans to disclose

the nature of these conflicts or the content of those emails.

I know from experience that responding to the content of

these messages at face value and ignoring the meaning is a mistake that you can

never recover from. It is also a mistake because it assumes that the people

representing corporations have a genuine interest in you as a human being. People – no matter how good they are – are

always expendable to the modern corporation and there is no better example than

healthcare companies. I also believe that because several of my previous supervisors

said it directly to my face.

I was very clear in my email that the

reason I was quitting was a decision that happened that day. It is good to maintain clear boundaries when

it comes to these decisions. Sometimes

there is a lot of emotion involved and when that happens a lot of charged rhetoric. By the time 9:30 PM rolled around – I was

very cool. I had been in a heightened

emotional state all day. That tends to

happen when people say things about me that are not true and try to make it seem

like I am personality disordered. By

heightened emotional state I generally mean a hyperadrenergic state. Anxiety, stress, tachycardia rather than anger. That distressed state resolved as soon as I

realized the situation with the administrators was hopeless and all I had to do

was quit. As soon as that occurred, I

was able to relax and fall asleep like nothing had happened. A complete cessation of the emails was also

helpful.

That decision in the last paragraph was very important to

me. As the son of a railroad engineer, I

was socialized to be very wary of any special interest (whether it was a

company or a union) that could affect your work or personal freedom. Being very

clear on what you want to experience was all part of that socialization and at

times it was fairly stark. There is a long learning curve. I did not really become an expert at it until

I walked away from a previous job 12 years ago. I thought I was going to work

at that job my entire career and retire – much like my Dad viewed his railroad job.

I recall my father showing me the front of his Brotherhood

of Locomotive Firemen and Engineers trade paper and angrily making the

following statement:

“Do you see this big house? That is where the President of the Union

Lives! Do you think he cares about what

happens to us?” (Fairly

certain my Dad would have probably used much more colorful language but I don’t want to embellish).

Of course not, Dad.

I heard a radio program several years ago about first-generation

white-collar workers from blue collar families.

According to the speaker, they were much less likely to integrate their

business lives into their social lives.

The example given was that they would not invite their boss over for

dinner. But nobody stated the reason –

and that is basic working-class distrust of management. Second-generation white-collar workers may

also have a much higher tolerance for bullshit than blue collar folks. In my

family of origin, bullshit was not a humorous or value free word. It was generally a pejorative.

There is also the way you exist in the work place. Some people need the social aspect at work for

many reasons including reassurance that they are in good standing. A lot of us like to keep our heads down, do

the work, and not comment on all of the social behavior in the workplace. We don’t want to hear about other peoples’

problems – not because we don’t care about our fellow man but because we were

raised to mind your own business.

I am in the latter category and find that it works very well. People I work with over time know they will

be treated fairly and they know that I am very loyal to them. That may be another reason why I react so

strongly when people make things up about me.

The boundaries are significantly less clear in a white

collar setting, especially with institutional rules and training on what

constitutes civility. Unless you are fired precipitously and escorted out by

security there are the superficial niceties – even if you are dying the death

of a thousand cuts. “Oh you’re leaving?

We are sorry to see you go! Let’s have some cake in the break room! Don’t be a

stranger!” All the while stories are

being spun about what happened to either make it seem like you were basically a

jerk or you were never there in the first place. At a previous job I endured

months of gaslighting and abuse. At one

point I asked my primary care doc for a prescription for a beta blocker just to

control my heart rate and blood pressure from the stress. I joke about taking

them like M&Ms, but at the time it was no joke. That was not going to happen again.

When I think about the range of normal and pathological

workplace dynamics I always come back to the work of the late Peter

Drucker. He was described as the world’s

greatest management thinker. One of

his key concepts is the knowledge worker. In other words, employees who were trained in

a profession – in many cases an independent professional. Drucker pointed out

that these employees need to be managed differently by virtue of the fact that

they know more about the business than their boss does. Further that they are not managed for widget

production as productivity. In the

current healthcare environment, the most highly trained employees are

physicians. They are treated like production workers and clerical workers rather

than knowledge workers and in many cases replaced en masse by other

workers who can do some of what they do.

As an example, I recently did a search through my health care system

looking for a primary care internist in the event that my current internist

retires. The search pulled up 50

practitioners and only 2 were physicians.

The way health care systems deal with knowledge workers is to either get

rid of them or ration them. All part of

the unending death spiral of low-quality care in America.

One of the big human-interest stories of the pandemic is

that medical school applications are apparently way up. The reason given is the presence of Anthony

Fauci, MD in the news. In all of these

clips, only a tiny fraction of Dr. Fauci’s expertise and body of work is

visible but his demeanor and consistent references to science make him easy to

identify with. He is a physician that others want to emulate. The problem for all of these

prospective medical students is that there are very few places any more where a

physician can practice at the top of what they were trained to do. There are practically no physician

environments that maintain an academic focus that was common in every setting that I trained at in the 1980s.

Apart from the workplace politics and all of the completely

unnecessary stress it produces my immediate consideration is finding a new

job. I do not need to work. I could

simply retire. When I was working a

burnout inpatient job – I fantasized about retiring early just to escape the

place. Since then, I have concluded that

I am still at the top of my game and have an excellent skillset to offer people

with significant psychiatric problems. These

services are clearly needed. In addition, I have a unique approach to

psychiatry that I think needs to be out there to counter the low-quality

checklist approach that has very little to do with psychiatry. The problem is finding the ideal environment

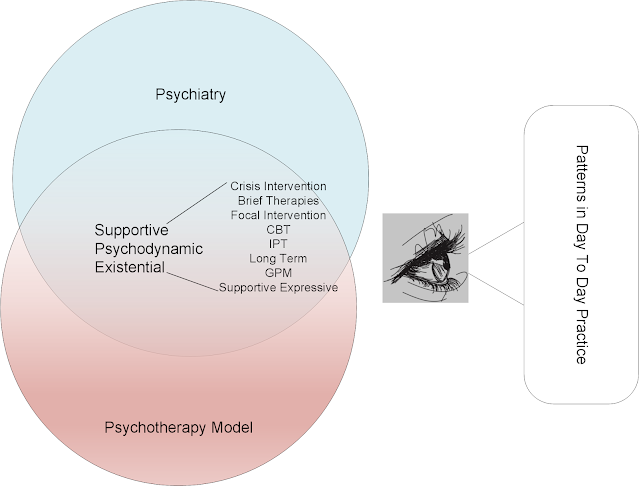

to utilize that skill set. The figure

below gives an example of the practice environments that I have worked in and

whether my skill set was utilized or marginalized.

Drawing on that experience whether I get another job at this point or retire depends on the following factors:

1: Malpractice

coverage: I could easily set up a private practice in the era of telepsychiatry

but any psychiatrist planning to retire at some point needs tail coverage. That is malpractice insurance through the

statute of limitations for malpractice in the state you practice in. In Minnesota that is three years and would

costs tens of thousands of dollars.

That’s right - three years paying out a good deal of money on the

hypothetical that you might be sued during that time – whether you have previously

been sued or not.

2: Practice

environment: The graphic below shows how

badly the practice environment has deteriorated with the invention of managed

care, pharmacy benefit managers, and an expensive labor-intensive electronic

health record (EHR). That means I have a

choice again between setting up my own office, hiring staff, buying and setting

up and EHR or going to work for a managed care company who has all of this but

expects me to become a template monkey and fill out 20-30 patient visit

templates per day. I use the term template

monkey out of respect for one of my colleagues who is a proceduralist and

told me at lunch one day that is what she had become. She presented it as a joke, but it is a

fairly depressing self-observation from one of the most highly trained MDs in

the profession and the hours it takes her to complete arbitrary forms that have

nothing to do with quality medical care.

While I am at it my inpatient and outpatient workflow is 30 minutes per patient follow up and 60-90 minutes for initial evaluations with some time in between for documentation and coordination of care. That coordination of care typically involves acquiring and reviewing records and speaking to the patient’s treating physicians. I also need to be able to dictate all of the notes rather than type them in to a template. I have yet to see dictation software work seamlessly enough, but I have seen transcription companies with industrialized versions do excellent job for a very low price. I need help from clerical resources, I don’t need to become a clerical worker.

3: Availability of

necessary equipment, tests, and specialists:

For 22 years I worked in a very collegial environment that was full of

medical and surgical consultants. I knew all of them and they knew me. There was mutual respect and plenty of

information exchange. We consulted informally

at lunch. If I had a patient with

complex problems – I would just do the evaluation, order all of the tests, make

a diagnosis and then call a consultant if necessary. I have not been in that environment for a

while and I am not used to leaving things hanging and depending that people

will follow my advice and see a cardiologist.

In fact, I know that people rarely follow through. Anyone who suggests that you can just kick

the can down the road, doesn’t really understand the practice of medicine

or psychiatry. In order to offer

treatment, I need to determine that the patient does not have serious

underlying illness and that I am not making any pre-existing conditions worse. So, I need a medically intensive

environment. I thought I could do without

it but that was a big mistake.

Apart from my current situation, this is a problem across the entire country. Medically trained psychiatrists and neuropsychiatrists are unable to find suitable practice environments. Managed care companies are quick to offer appointments with any prescriber for anxiety and depression or even more complicated problems. This is a system wide problem even though there is no organized system of mental health care in the country. If I get lucky and find the resources I need – the system will be lucky – at least in the geographic area where I can serve patients. It is a basic fact that the necessary practice environment for most medically intensive psychiatrists has become a fantasy in the United States. That fantasy could easily be remedied by a national work force supplying psychiatrists with what they need and paying them as employees.

If I am not fortunate enough to find the right practice environment

– I will be enjoying retirement and to me a lot of that will still be studying

psychiatry, medicine, and science. It is

what I do and I enjoy doing it.

Old patterns of behavior die hard – at least for me.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

Supplementary 1:

My official last day was the close of business on Tuesday

January 19 and that is why this is being posted later that same day.

I do wish my fellow former employees the very best (including

the administrators) and hope that everything goes well for them. After I announced my resignation, I received

at least 50 very positive emails telling me that they liked working with me and

wishing me well in the future. In many

cases they were extremely complimentary. We all worked together to help people

solve very difficult problems in a highly constrained environment. We were

typically successful to some degree. For all of the compliments all that I can

say is thank you and:

“The light that shines on me – shines on you”.