Sunday, April 22, 2018

American Academy of Sleep Medicine versus Minnesota Medical Cannabis Program

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) came out with a position statement about the use of medical cannabis for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). In brief they think it is not a good idea. The entire statement can be read at the link. I think that it is important to keep in mind that they concerns about safety and efficacy are generally dependent on the fact that like most of the conditions on the Minnesota list, there is minimal to no scientific data to back up the suggested uses.

The AASM is not the first professional society to take a position on medical cannabis. One of the first purported applications of medical cannabis was for glaucoma. The American Academy of Ophthalmology has a position statement on Cannabinoids for Glaucoma that reviews the history of this application and concludes that although cannabinoids can lower intraocular pressure, the duration of this effect is too short and the side effect profile too problematic for cannabinoids to be used for this application. The statement points out that long acting cannabinoids for this application were recommended by the Institute of Medicine in 1999, but as of 2018 statement - there has been not suitable cannabinoid derivative.

That brings me back to the familiar refrain on this blog and that is the fallacy that cannabinoids or any street drug for that matter represents some form of miracle drug. Humans have been aware of cannabis for many applications for about 5,000 years. A reasonable question is why some miracle application or even one less than a miracle has not been found at this point in time. Why for example, were opioids developed as effective pain medications from the natural compounds over the same period of time? I have attended the lectures on physicians who advocate for medical cannabis. Some of them invoke Chinese medicine and quasi-scientific explanations like the entourage effect about why the whole plant needs to be smoked. I don't really see a need for physicians to certify people to access these largely unproven treatments, especially when medical colleagues are describing them as potentially unsafe and ineffective.

I have no problem with the state of Minnesota supplying medical cannabis to people with a condition that has no clear cut treatment. I have no concerns about the state supplying cannabis to people who are terminally ill. I do have a problem when cannabis is listed as a treatment when in fact there is little to no evidence that it is effective and vastly superior treatments exist. Glaucoma and obstructive sleep apnea are two of these conditions. From a purely psychiatric standpoint post traumatic stress disorder, and autism have existing treatments and autism has a newly approved treatment. In the case of Tourette's syndrome and other movement disorders - the data remains very preliminary.

As a prescribing physician, I have serious doubts about the thinking that goes into prescribing cannabis as an actual medication. I prescribe medications every day. These medications are all approved for use by the FDA. There are specific indications and off label uses. There are potentially serious side effects. The medications have to be prescribed to take the patient's chronic illnesses into account. For example, I would not prescribe a sedative to a patient who I thought might have obstructive sleep apnea. Prescribing cannabis, even in a special program that eliminates smokable cannabis continues to not make any sense to me.

The list at the top of this page is directly from the Minnesota Medical Cannabis program as of today. It lists all of the current conditions that qualify a person to take it. I see the list as a political compromise to delay and potentially thwart the recreational marijuana movement. It should not be a surprise that medical cannabis has always been a mainstay of the strategy to legalize recreational marijuana. While that drama plays out - I hope that people in Minnesota don't forgo effective medical treatment for medical cannabis. Today that means CPAP for obstructive sleep apnea and glaucoma drugs and surgery for glaucoma.

There is no evidence that medical cannabis can come close to the medical effectiveness of those options. At the political level - this is also a great example of how politics negatively impacts quality medical care.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

References:

1: Ramar K, Rosen IM, Kirsch DB, Chervin RD, Carden KA, Aurora RN, Kristo DA, Malhotra RK, Martin JL, Olson EJ, Rosen CL, Rowley JA; American Academy of Sleep Medicine Board of Directors. Medical cannabis and the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(4):679–681.

2: Petitions to Add Qualifying Medical Conditions to the Medical Cannabis Program. This document documents the review process for adding qualifying conditions to the list. Link

Graphic:

The table at the top of this post is directly from the Minnesota Medical Cannabis web site and is used here as a public document.

Saturday, April 21, 2018

First FDA Approved Cannabis Product - Epidiolex

|

| Cannabidiol (CBD) |

Headlines yesterday were that the FDA Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee approved a cannabis product for the treatment of seizures. The draft agenda for that meeting is available on the FDA web site but no vote or minutes of the meeting. This has been a widely hyped application of medical cannabis since the term was first used to try to start the legalization of cannabis products. Ironically the first example of a patient used as an example for this application did not have the syndrome in question.

At the time I am typing this post there is no FDA approved package insert for the compound and no prescribing information available on the manufacturer's website. There is a considerable amount of detail in the patent that is available online. The patent focuses on the use of cannabidiol in treatment resistant epilepsy including Dravet syndrome; myoclonic absence seizures or febrile infection related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES). The patient states that when cannabidiol is used for these disorders the total reduction in seizure frequency is 50-70% but as high as 90-100%. The product is formulated to be used separately or with other anti-epileptic drugs (AED). The patent suggests that the formulation is comprised of highly purified cannabidiol extract (98% w/w) with most of the psychoactive components - tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) removed.

The epidemiology and treatment of epilepsy especially Dravet's syndrome is reviewed in the patent. It is clear from that data that there are no good treatments for these disorders and that conventional AEDs are partially effective at best. The four treatment scenarios (non of which are randomized controlled clinical trials) all demonstrate efficacy for CBD in intractable epilepsy. These results are included in the table below.

Trials

|

Treatment

|

General

Response

|

Best Response

|

N=27

children and young adults

Dx: severe

childhood onset treatment resistant epilepsy (TRE)

|

Initial

dose: CBD 5mg/kg/day titrated to a max of 25 mg/kg/day in addition to

baseline AEDs

|

-after

3 months of therapy, 48% of patients had an equal to or greater than >50%

reduction in seizures.

-

|

- 2

patients were seizure free at three months

- 6

patients had a 90% reduction in seizures at three months

|

N=9

children and young adults with treatment-resistant Dravet syndrome

|

- as above

|

- after

3 months of therapy, 56% of patients had an equal to or greater than 50%

reduction in seizures,

|

- 2

patient were seizure free at three months

-3

patients has a 90% reduction of seizures at three months

|

N=4 patients

with myoclonic absence seizures who were taking at least two concomitant

anti-epileptic drugs

|

-as above

|

after 3

months of therapy, 2 of the patients had an equal to or greater than 50%

reduction in seizures, 1 patient (25%) had a 90% reduction at the three month

stage.

|

-0 patients

were seizure free

-1 patients

with a 90% reduction of seizures at three months

|

N=3

patients with FIRES (febrile infection related epilepsy syndrome)

|

-as

above

|

- 2/3

children has a 90% reduction in seizures

|

-2/3

children had a 90% reduction in seizures and regained some motor and intellectual

functioning.

|

A mysterious part of the patent process is that this is a simple organic chemistry extraction of CBD from cannabis plants and then resuspending for oral dosing. The authors specify that THC is essentially removed. The dosing is done in a standard mg/kg dose that would be expected for any medication. That dose range appears to be part of the patient. Does this patent mean that any CBD extracted from cannabis is the intellectual property of this company or is there more to it than that? If that is the case then any product with a CBD/THC ratio could be patented and there are currently 11 of these compounds prepared by a similar extraction process in the Minnesota Medical Cannabis Program. Is each one of these compounds patentable? Or is there some additional information about the formulation that is not included in the patent that would make this formulation more unique? At one point the patent states that the CBD can be synthesized as well as extracted.

The market for this product is potentially significant, if it works in less severe forms of epilepsy. Will it work for example in the case of a person who has a few seizures per month after their AEDs have been optimized? Can that person take the necessary dose of CBD and not experience significant side effects? Will the company or other companies try to get another FDA approved indication for CBD related products from the FDA? I suspect the standard will be higher in patients where there are compounds of equal or better efficacy. Will physicians prescribe CBD derived drugs off-label to people requesting them for philosophical reasons (eg. I want to be treated with a substance derived from a botanical)? Will the positive effects noted in these small trials persist as more and more people with epilepsy are exposed to the drug? Will there be more significant side effects with post marketing surveillance and maintenance use? There are still a significant number of people who do not appear to respond very well to CBD. Those are some of the questions I had considering the implications of this product release.

On theoretical grounds, a key question is whether the utility of this compound in severe epilepsy will lead to additional drug discovery of more compounds for this difficult to treat problem. For now, the FDA has made a sound decision getting this compound into the hands of the physicians who treat these disorders on a day to day basis.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

References:

1: Devinsky O, Marsh E, Friedman D, Thiele E, Laux L, Sullivan J, Miller I, Flamini R, Wilfong A, Filloux F, Wong M, Tilton N, Bruno P, Bluvstein J, Hedlund J, Kamens R, Maclean J, Nangia S, Singhal NS, Wilson CA, Patel A, Cilio MR. Cannabidiol in patients with treatment-resistant epilepsy: an open-label interventional trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016 Mar;15(3):270-8. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00379-8. Epub 2015 Dec 24. Erratum in: Lancet Neurol. 2016 Apr;15(4):352. PubMed PMID: 26724101.

4: Perucca E. Cannabinoids in the Treatment of Epilepsy: Hard Evidence at Last? J Epilepsy Res. 2017 Dec 31;7(2):61-76. doi: 10.14581/jer.17012. eCollection 2017

Dec. Review. PubMed PMID: 29344464.

5: FDA Briefing Document Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting April 19, 2018 NDA 210365Cannabidiol

5: FDA Briefing Document Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting April 19, 2018 NDA 210365Cannabidiol

Wednesday, April 18, 2018

A Report From The Minnesota Medical Cannabis Program

I have described the Minnesota Medical Cannabis Program in a previous post. It is a unique program because it does not provide smokable cannabis for medical purposes. All of the cannabis is in a form that is vaporized, edible, absorbed through the oral mucosa, or transcutaneously after application to the skin. It is produced by two companies and made into products of varying amounts of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), cannabidiol (CBD) . In the original matrix from the first post there appeared to be a total of about 11 products based on the THC and CBD ratios. For the purpose of this report the cannabis products were classified base on ratios of cannabinoids and route of administration according to the following table:

The program came out with a report on the experience of patients with chronic intractable pain using the program this week. They produce frequent reports and this is the latest. Although it is not a scientific study of the associated issues of pain relief it is interesting because of a number of considerations not the least of which is what happens when a state starts to manage a CSA Schedule 1 drug on their own and come up with their own process for certification and use.

The report details the cohort of patients who were qualified on the basis of intractable pain according to the following definition: “pain whose cause cannot be removed and, according to generally accepted medical practice, the full range of pain management modalities appropriate for this patient has been used without adequate result or with intolerable side effects.” (p 4).

The report focused on the results and side effects of 2245 patients certified by various practitioners for intractable pain between August 1, 2016 and December 31, 2016. It contains basic demographics of the patients and practitioners as well as a breakdown of the possible origins of their chronic pain. All of these details are available in the original report and I encourage any interested reader to find the details there. I am interested in the type of medical cannabis being used and the outcomes.

These details are fairly interesting from a descriptive standpoint. For example, just using the product definitions there is a distribution of how the products are purchased. The following bar graph illustrates the distribution of purchased products by THC and CBD content:

The report gets into more specific details about the types of THC and CBD products in each category and the average ingestion of these products per day in milligrams (mg). I am reproducing the first of a 4 page table here that contains progressively fewer patients in each strata:

It is apparent that very high THC products that are inhaled or ingested predominate the product distribution. Although the largest single group of patients were averaging 81.5 mg/day THC and 0.6 mg/day CBD the range is significant from 4.4 to 553.8 mg/day THC and 12.2 to 1,439.2 mg/day CBD.

Patient and treatment providers were asked to rate their degree of benefit from the medical cannabis program on a Likert scale where 1 = no benefit and 7 - great deal of benefit. Using that system 61% of the patients rated their experience as a 6 or 7 compared with 43% of the healthcare professionals rating the patient benefit as a 6 or 7. Specific benefits were rated and the top three included pain relief (56%), sleep improvement (10%), and reduction in pain medications and side effects (7%).

An area of interest in the report is whether or not the patient is reducing the amounts of other pain medications used in response to the use of medical cannabis. This question is asked to the certifying health care professionals. For this report, 586 responses of a total of 692 were used to determine that pain medications were reduced in 58% of the cases and not reduced in 48% of the cases. 221 reduced an opioid with 127/221 reducing the opioid by 50% or more. In addition, 16 reduced a benzodiazepine and 128 reduced a pain medication "other than an opioid or benzodiazepine" - but benzodiazepines are not pain medications. The full list of medications reduced or discontinued are available in Appendix E. Minnesota does have a Prescription Monitoring Program for controlled substances making it possible to quantify and confirm all of this data rather than depending on survey results.

The section of the report that I found most interesting was the section on a standard group of 8 symptoms followed in this patient group for improvement or no improvement. These symptoms are listed in the tables below.

The response options are on a standard analogue scale where 10 is the worst possible symptom and 0 is the symptom is not present. The report listed the results of this scale applied to intractable pain patients as shown in the table below.

It is an interesting report in that it gives improvements in symptoms over 4 months as well as the percentage of patients a 30% improvement in symptoms at some point in the initial 4 months, the percentage of patients who had a 30% symptoms improvement in the 4 month follow-up period, and the percentage of patients who had the 30% symptoms improvement and maintained it for at least 4 months. Only 11% of the pain patients maintained a 30% improvement in pain symptoms over the 4 month follow up despite higher ratings of initial pain relief. The most significant improvements were in nausea and vomiting.

Side effects were reported in the final section with about 10% of patient reporting severe side effects. These side effects included somnolence, sedation, headaches, dizziness, lightheadedness, confusion, fatigue, abdominal pain, mental fogginess, inability to concentrate, anxiety, panic attacks, and insomnia. Physical side effects were reported roughly twice as often as mental side effects and most were in the mild to moderate range. A typical metric found in clinical trials - medication discontinuation because of side effects was apparently not determined. In a series of statements included in the report, one patient stopped because of a lack of efficacy and there was a suggestion that stopping could occur for that reason or financial reasons but the data was not clear.

Although the current report is focused on intractable pain a couple of things seems clear. First, these reports are not scientific. There are no comparison drugs or placebos. Medical cannabis is added in many cases to a combination of existing opioid pain medications and benzodiazepines. In a purely qualitative sense, they do show what products are preferred by customers and these products contain significant amounts of THC. Second, in the case of the 8 symptom rating pain relief from medical cannabis appears to be modest at best. A significant number of patients acknowledged severe side effects, but were these side effects of the same level of severity that might be seen in a clinical trial? In those patients who replaced opioids or to a lesser extent benzodiazepines - was that because the initial medications were ineffective for pain or because cannabis has superior effects on pain?

The most interesting part of the data to me is that fact that medical cannabis is highly promoted for chronic pain. That promotion was initially political - for the purpose of legalizing medical cannabis. Currently it takes the form of cannabis saving people from opioid overdoses and this report makes an attempt to record reduced amounts of opioids use due to the cannabis. The problem is that it is all survey data. There are no standardized doses of cannabis and no attempt to determine a placebo effect. Physicians used to reading clinical trials need to ask themselves: Is a patient interested in using medical cannabis in Minnesota capable of answering the questions in an unbiased manner? Will their interest/belief in medical cannabis influence survey results? And if that is true - what does it mean that medical cannabis ends up with such a poor result for pain relief over a period of 4 months? I have concerns about the survey results based on my interviews with thousands of cannabis smokers. Although I am seeing people with significant addiction problems, I don't see the side effect frequency of insomnia, anxiety, panic, and paranoia that I am used to hearing hearing about. And in this group, I can't help but wonder how many of them have significant addictions? I also don't see a discussion of the fact that many opioid users commonly switch to cannabis when the opioid supply runs low or they make an attempt to stop using. There are potentially several mechanisms occurring in this population in addition to pain relief and side effects.

Another issue indirectly addressed by this report is what happens when you do an end run around the FDA? I have certainly been a critic of the FDA and its regulatory processes, but in the end there is always a study available for public discussion. That study typically has much more information content about drug efficacy and tolerability than the current Minnesota study because of the scientific design. This report is the type of data that you get when that regulatory hurdle is ignored.

The direction and legacy of medical cannabis in Minnesota seems to be contingent on the status of recreational cannabis. The program has been criticized for being too expensive compared with smokable cannabis. If Minnesota legalizes recreational cannabis, that may be the preferred route by many of the people in this program. Questions about the efficacy of cannabis in intractable pain remain unanswered despite all of the details in this report.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

References:

1: Minnesota Department of Health Office of Medical Cannabis. Intractable Pain Patients in the Minnesota Medical Cannabis Program: Experience of Enrollees During the First Five Months. Report

2: Desrosiers NA, Ramaekers JG, Chauchard E, Gorelick DA, Huestis MA. Smoked cannabis' psychomotor and neurocognitive effects in occasional and frequent smokers. J Anal Toxicol. 2015 May;39(4):251-61. doi: 10.1093/jat/bkv012. Epub 2015 Mar 4. PubMed PMID: 25745105.

Graphics:

All tables excerpted from reference 1 as a public document with no copyright.

Tuesday, April 10, 2018

Sensational Antidepressant Article from the New York Times

Take some quotes taken out of context, the suggestion that doctors know less about the problem than the New York Times does, and the suggestion that you may be "addicted to antidepressants" and what do you have - the latest article on antidepressants by the New York Times. Although the New York Times has never been an impressive resource of psychiatric advice they continue to play one and the latest article Many People Taking Antidepressants Discover They Cannot Quit is a great example.

The reader is presented with numbers that seem to make the case "Some 15.5 million Americans have been taking the medications for at least five years. The rate has almost doubled since 2010, and more than tripled since 2000." and "Nearly 25 million adults, like Ms. Toline, have been on antidepressants for at least two years, a 60 percent increase since 2010." Guaranteed to shock the average reader, especially in a culture that systematically discriminates against the treatment of mental illness.

Adding just a little perspective those figures translates to 15.5M/254M = 6.1% and 25M/254M = 10% of the adult population in the US. Looking at the most recent epidemiological estimates of depression in the US 1990 - 2003 shows one year prevalences of 3.4 - 10.3% of the adult population. The lifetime prevalences from some of those studies 9.9-17.1%. It seems that the claims of antidepressant utilization may be overblown relative to the epidemiology of depression and the number of people disabled by it. The authors go on to quote a study on the overutilization of antidepressants on data obtained from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) study. These same authors have quoted an increase of antidepressant use of 10.4%. This same study estimated a lifetime prevalence of depression of 9.5%.

Depression alone is not the sole indication for antidepressants. Anxiety disorders is another FDA approved indication. Anxiety disorders can add an additional 3% 1 year prevalence and 5-6% lifetime prevalence. About 16.5% of the population has headaches and antidepressants are used to treat headaches. Another 6.9-10% of the population have painful neuropathies that are also an indication for antidepressant treatment. Over a hundred million Americans have chronic back pain another indication for a specific antidepressant. The main reference points to a study (3) that suggests only about 7.5% of antidepressants are prescribed for nonpsychiatric conditions. Only 65.3% of the prescriptions were for "mood disorders. A study looking at antidepressant drug prescribing in primary care settings in Quebec Canada (5) provides specific data and concludes that 29.4% of all antidepressant prescriptions were not for depression or anxiety but for insomnia, pain, migraine, menopause, attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder, and digestive system disorders. Those same authors go on in a subsequent paper to provide a detailed analysis of the off-label use of those antidepressants.

The number of antidepressant prescriptions is far less drastic when taken in that context. I am not arguing that every person with an eligible condition should be on antidepressants. I am definitely saying that given the large numbers of people who will potentially benefit - the number of antidepressant prescriptions is not as outrageous as portrayed in the article.

What follows is a brief descriptions of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms and the fact that the medical profession doesn't know what to do about it. This is certainly not the case in any setting where I have practiced. Discontinuation symptoms are well know to occur with SSRI and SNRI medications. I routinely describe them and their varying intensity as part of the informed consent procedure when I prescribe these medications. The reality is that 20% of people will stop taking antidepressants in the first month after getting a prescription. Many will just get the prescription and never start. An additional 20-30% will stop in the next 3-4 months. Stopping antidepressants without medical guidance is so common that I routinely ask patients if they have abruptly stopped at any point when I am making any changes in their medications. The majority have stopped without getting any of the discontinuation symptoms. I qualify that by the fact that I have not prescribed paroxetine in 30 years because I considered it to be a problematic medication and I have a very low threshold for stopping antidepressants if I don't believe they are tolerated. Even in their referenced study (2) the authors state: "In one national study, for example, only about one-quarter of adults initiating antidepressants for new episodes of depression continued to take their medications for 90 days...". Does that sound like it is a medication that is difficult to stop?

They don't stop there. After making it seem like we are in the midst of an antidepressant epidemic and that people are unable to stop antidepressants they make an even more absurd argument - doctors are unable to help patients get off antidepressants. Before I go into their details consider this. I work at a facility where we routinely detox people off high doses of the most addictive drugs in the world. If we are able to do that, why would a doctor not be able to figure out how to discontinue a non-addictive antidepressant? This specific statement really had me rolling my eyes:

"Yet the medical profession has no good answer for people struggling to stop taking the drugs — no scientifically backed guidelines, no means to determine who’s at highest risk, no way to tailor appropriate strategies to individuals."

Do I really need a study to do something that I have been doing successfully for 30 years? Tapering people off of medications is something that every physician has to do. Successfully using antidepressants means being able to taper and discontinue one and start another or taper and discontinue one while starting another or starting another and eventually tapering and discontinuing the original antidepressant. That is not innovation - that is standard psychiatric practice.

I can only hope that the quotes from family physicians that follow were totally out of context. Statements about "parking people on these drugs for convenience sake." and that the "state of the science is absolutely inadequate" are ludicrous. I would say if you have to park somebody on a psychiatric drug or have questions about how it is used - it is time to send that patient to see a psychiatrist. Nobody should ever be "parked" on a drug.

These physicians seem to have lost sight of the fact that they do not have similar problems prescribing equal amounts of antihypertensive medications and leaving people on them indefinitely. There is no rhetoric about "parking" somebody on an antihypertensive medication or a cholesterol lowering drug or a medication for diabetes. The fact that depression is the leading cause of disability in the world seems to be ignored. The fact that up to 15% of people with depression die by suicide is not mentioned. The suggestion is that this disabling and potentially fatal condition should not be addressed as rigorously as other chronic illnesses.

In the midst of all of the confusion created in this article, the authors fail to point out the likely cause of increased antidepressant prescriptions but they quote one psychiatrist who comes close. He points out that the increase in antidepressants is due to primary care physicians prescribing them after brief appointments and (probably) not being able to follow the patient up as closely as a psychiatrist. This was one of the main findings in the paper by Mojtabi and Olfson (2). The specific quote "...the increase in long-term use (of antidepressants) was most evident among patients treated by general medical providers."

What is really going on here? This blog has repeatedly pointed out that mental health care and treatment by psychiatrists has been rationed for about 30 years. The result of that rationing is that there are few reasonable resources to treat all kinds of mental illnesses. With that end result, the argument is now being made that we really don't have to build the infrastructure back up - we just need to shift the burden to primary care clinics. In order to make it more simple for them we can just screen people with a rating scale for depression (PHQ-9) or anxiety (GAD-7) and treat either symptoms with a medication. That way we can not only ration psychiatrists, but we can also ration psychologists and social workers who could possibly treat many of these patients with psychotherapy alone and no medication. For that matter, we could treat a lot of these patients with computerized psychotherapy - but managed care organizations will not. State governments and managed care organizations will screen people, make a diagnosis based on a rating scale, and put that person on an antidepressant medication as fast as possible.

That is a recipe for high volume and very low quality work. A significant number of those patients will not benefit from a medication because they do not have a compatible diagnosis. A significant number will not benefit from the medication because it is not correctly prescribed. In order to compensate for that inadequacy, a model of collaborative care exists that provides a psychiatric consultant to the primary care clinic. That psychiatrist never has to directly see the patient. The collaborative care model depends on putting patients on antidepressants as soon as possible and even more classes of psychiatric medication.

That is the real reason for increased antidepressant prescriptions and people taking them. It is not because nobody knows how to prescribe them or stop them. It is not because they are "addictive". It is because there is a lack of quality in the approach to diagnosing and treating depression in primary care settings and that is a direct result of federal and state governments and managed care organizations.

To be perfectly clear I will add a series of rules that will not question the current business and political rationing of mental health resources but will address the problem of antidepressant over prescribing and antidepressant discontinuation:

1. Stop screening everyone in primary care clinics with rating scales - there is no evidence at a public health level that this approach is effective and it clearly exposes too many people to antidepressants and other medications. I am actually more concerned about the addition of atypical antipsychotics to antidepressants for augmentation purposes when nobody is certain of the diagnosis or reason for an apparent lack of response and nobody knows how to diagnose the side effects of these medications.

2. Provide any prospective antidepressant candidate with detailed information on antidepressant discontinuation syndrome - including the worse possible symptoms. While you are at it give them another sheet on serotonin syndrome as another complication of antidepressants. It is called informed consent. I encourage the New York Times not to write another article about serotonin syndrome.

3. Triage depressed and anxious patients with therapists rather than rating scales - brief, focused counseling, CBTi for insomnia, and computerized psychotherapy all have demonstrated efficacy in addressing crisis situations and adjustment reactions that do not require medical treatment.

4. Refer the difficult cases of discontinuation symptoms to psychiatrists who are used to treating it.

5. Don't prescribe paroxetine or immediate release venlafaxine - both medications are well know to cause discontinuation symptoms and they are no longer necessary.

6. Every physician who starts an antidepressant needs to have a plan to discontinue it - the idea that a patient needs to be on a medication "for the rest of their life" in a primary care setting is unrealistic. If that determination is to be made - it should be made by an expert in maintenance antidepressant medications and not in a primary care clinic.

7. Every patient should be encouraged to ask to see an expert if either their medication prescribing or treatment of depression is not satisfactory. The standard for treating depression is complete remission of symptoms - not taking an antidepressant. If you are still depressed - tell the primary care clinic that you want to see an expert.

In an ideal world, people with severe depression would be seen in specialty clinics for mood disorders, by psychiatric experts who could address every aspect of what they need. That used to happen not so long ago. It still happens in every other field of medicine.

But quality care like that is no longer an option if you have depression.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

1: Carey B, Gebeloff R. Many People Taking Antidepressants Discover They Cannot Quit. New York Times April 7, 2018.

2: Mojtabai R, Olfson M. National trends in long-term use of antidepressant medications: results from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014 Feb;75(2):169-77. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08443. PubMed PMID: 24345349.

3: Mark TL. For what diagnoses are psychotropic medications being prescribed?: a nationally representative survey of physicians. CNS Drugs. 2010 Apr;24(4):319-26. doi: 10.2165/11533120-000000000-00000. PubMed PMID: 20297856.

4: van Hecke O, Austin SK, Khan RA, Smith BH, Torrance N. Neuropathic pain in the general population: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Pain. 2014 Apr;155(4):654-62. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.11.013. Epub 2013 Nov 26. Review. Erratum in: Pain. 2014 Sep;155(9):1907. PubMed PMID: 24291734.

5: Wong J, Motulsky A, Eguale T, Buckeridge DL, Abrahamowicz M, Tamblyn R.Treatment Indications for Antidepressants Prescribed in Primary Care in Quebec, Canada, 2006-2015. JAMA. 2016 May 24-31;315(20):2230-2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.3445. PubMed PMID: 27218634.

6: Wong J, Motulsky A, Abrahamowicz M, Eguale T, Buckeridge DL, Tamblyn R.Off-label indications for antidepressants in primary care: descriptive study of prescriptions from an indication based electronic prescribing system. BMJ. 2017 Feb 21;356:j603. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j603. PubMed PMID: 28228380.

Saturday, March 31, 2018

The Prostate Is On The Wrong End - Why Should We Worry?

There is always a lot of news about the prostate these days. It has become the poster child of the evidence based crowd. Just last week I saw the headline: "Men are more likely to die in a structure fire than from prostate cancer." This is all part of the political approach to epidemiology that emphasizes that even though most men will develop some type of prostate cancer by the age of 85, they are likely to die of other causes. Therefore PSA screening is not useful because it leads to more invasive procedures with complications like prostate biopsy and then procedures with even more complications like radical prostatectomy. The sordid aspect of this business has been pointing out the options that several celebrities who made decisions about prostate cancer and therapies. Depending on the side you take - you will cheer the representative decision. I noticed that the celebrities who died from prostate cancer including misdiagnosis are omitted from that equation.

In clinical practice, young men with recurrent prostatitis have always been a red flag for me. They often end up on very long courses of antibiotics and seem to have chronic symptoms. The symptoms don't match descriptions of acute prostatitis that are more similar to an acute urinary tract infection. The anatomy of the male urinary tract often needs to be reviewed, especially the relationship of the prostate and the urethra. I have treated many young men who were very angry at their Urologists because of these chronic symptoms even though they were not medically explained. If I see these situations today - I typically call the Urologist and suggest treatment only for a clear cut case of prostatitis and whether they have noticed any changes in the patient's behavior.

My focus in this post is bladder outlet obstruction and all of the associated phenomenon due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. According to UpToDate (10) it is more common in men and 10% of men greater than the age of 70 and 1/3 of men over the age of 80 will develop it. Treatment is necessary to prevent renal complications, bladder dysfunction, infection and in severe cases delirium. I don't intent to focus on the urological treatment - only as required to explain the situation. I am more interested in what happens with this disorder and how the presentation may appear to be psychiatric. I think that this is a neglected are in the literature. Please send me any references that I may have missed.

The neuroanatomy and physiology of micturation is a complicated process. At the local level, micturation is innervated by both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. The sympathetic efferent innervation inhibits β3 adrenoreceptors to relax the detrussor muscle of the bladder and activates α1 receptors at the level of the urethra. Parasympathetic efferent innervation activates M3 muscarinic receptors in bladder smooth muscle and motor neurons stimulate acetylcholine nicotinic receptors in the external urethral sphincter to cause contraction. Relaxation of that sphincter muscle is facilitated by postsynaptic parasympathetic neurons that release ATP and nitric oxide. The efferent arm of micturation requires close coordination of that combination of motor and sympathetic nervous system components.

The afferent side of this function begins at the level of the bladder epithelium. These cells have complex signalling functions that can lead to local vascular and muscular responses in addition to sensory information being sent to higher centers. Bladder epithelium and underlying myelofibroblasts may function to send a stretch signal as the bladder fills. The actual mechanism that initiates that signal was not clear from the review I read. A local acetylcholine based mechanism was thought to led to local bladder contractions. This was thought to be the reason that antimuscarinic agents were used for bladder spasticity.

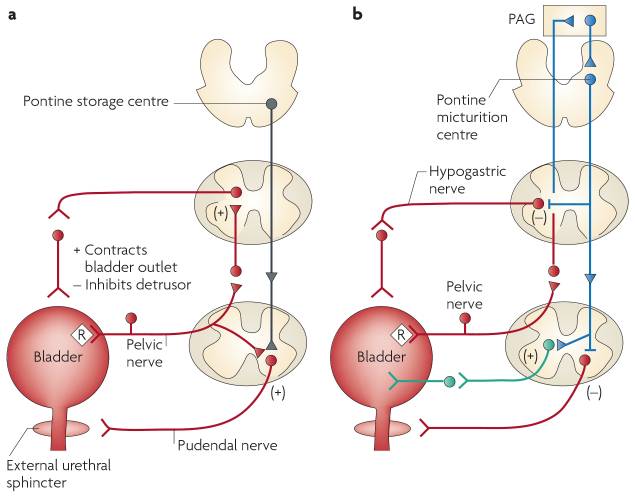

This process was not delineated very well until about the past 10-15 years. A combination of brain imaging during micturation and neuroscience techniques applied to determine the anatomic pathways. One of those techniques was the application of pseudorabies virus to the wall of the rat bladder. This technique leads to retrograde transport of the virus into affected structures. Viral markers go to structures in both the peripheral and central nervous system. A wide variety of cortical and subcortical structures are involved including the raphe nuclei, locus ceruleus, red nucleus, periaqueductal grey area, pontine micturation center, and cerebral cortex are involved. The parasympathetic excitatory reflex pathway is presented in the diagram below (1).

The circuits controlling continence

and micturation are shown below. The diagram on the left is the storage reflex

consisting of negative feedback to inhibit detrusor contractions and increase

urethral sphincter activity. In the voiding phase intense afferent activity in

the spinobulbospinal reflex pathways passes the pontine micturation center.

That leads to descending parasympathetic activity stimulates detrusor muscle

and inhibits urethral sphincter activity at the bladder outlet. Associated

structures at the brain level have been suggested by functional imaging

studies. The central mechanism suggested is release of tonic inhibition of the

micturation center by the frontal cortex. Some of the associated structures are

important limbic structures and have connectivity to other organ systems by

sympathetic tracts.

In the case of BPH, there is

increased intraluminal pressure in the proximal urethra or bladder outlet. This

alters the set point of the system. Voluntary voiding occurs but at higher

residual volume and detrussor pressure. That leads to typical symptoms of

frequent voiding, decreased urine flow, and small volumes. In extreme cases

total obstruction can occur on at least a temporary basis requiring temporary

catheter insertion to maintain urine flow.

Getting back to psychiatry, let me

illustrate the relevance of the problem.

Case 1: JD -

a 68 yr old man in fairly good health until about 3 months earlier. At that

time he started to experience profound sleep problems. He has obstructive sleep

apnea (OSA) and uses CPAP - but his parameters looking at the AHI and air

leakage are unchanged. He now has frequent nocturnal panic attacks that awaken him. Upon waking his heart is

pounding and he has palpitations. He purchased a single lead hand held ECG

device that takes a 30 second rhythm strip and recorded one ventricular

premature contraction in 30 seconds. He consulted both his pulmonologist and

cardiologist involved in the original OSA diagnosis. The pulmonologist looks at

his CPAP parameters and concludes that he does not need another sleep study.

The cardiologist tells him that these VPCs are benign and there is nothing to

worry about. JD is concerned because this is a definite change in his health

status and neither physician is concerned.

He went in to see his primary care

physician who examines him and jokes about the cardiac-bladder connection. He

does a prostate exam and concludes that his prostate is "about the 90th

percentile". No further evaluation or treatment is recommended.

His wife notices that he is sitting

up in a chair in the bedroom a lot more at night. He explains that he is having

palpitations and is very anxious at night. His wife tells him to see the

psychiatrist who is treating her for panic attacks. He makes an appointment and

goes in about 2 weeks later.

The psychiatrist does a complete

history and sleep assessment and concludes that these are not typical panic

attacks. JD recalls a number of dreams where he is running, exerting himself,

or very fearful in the dreams. He awakens with his heart pounding and

experiencing the irregular beats. As soon as he is able to void, the

tachycardia and palpitations resolve. The psychiatrist thinks they are related

to the episodes of urinary frequency and urgency associated with BPH and that

therapy targeted to address the bladder outlet obstruction will lead to a

resolution of the sleep problems and panic attacks. Since seeing his primary

care physician JD has acquired a wrist watch with a vibrating alarm. He uses it

to wake himself up at 2AM and 4AM and finds that pre-emptive bladder emptying

greatly reduces but does not eliminate the nocturnal panic attacks entirely.

The psychiatrist refers JD to a Urologist. He is assessed and treated with

tamsulosin - an alpha blocker that relaxes smooth muscle fibers in the bladder

neck and prostate. Taking the medication results in a significant improvement

but not a normalization of bladder emptying. JD is back to voiding once a

night. He has no nocturnal panic attacks or dreams where he is fearful or

exerting himself.

The background and case

illustrate a few points. Now that micturation is no longer a black box in the

brain, the affected structures and the types of symptoms that can be generated

need to be considered. It is an easy mistake to treat what seems like a panic

attack like a panic attack - especially when previous physicians have not been

impressed enough to work up or treat the problem. Nocturnal panic attacks in a

68 year old man with no previous psychiatric history suggests that there are

possible medical causes for these symptoms and in this case it was bladder

outlet obstruction. The closest syndrome to account for the findings in this

case is cystocerebral syndrome - typically delirium in elderly men with acute

urinary retention where no other cause can be identified (3-9). Decompressing

the bladder typically results in resolution of the acute confusion. That has

led several of the authors to postulate that an adrenergic rather than

anticholinergic mechanism is involved. I don't not have access to all of these papers

and cannot tell if the authors documented some of the problems noted in the

case described here (tachycardia, palpitations, VPCs, anxiety and panic) but

they are all presumptive hyperadrenergic mechanisms.

Whether sleep disturbance, panic

attacks, and eventual delirium can all occur in the same men with bladder

outlet obstruction is not known at this point. That progression of symptoms

seems to make sense but it is not well documented and may just be another

syndrome waiting for better characterization. One of the main differences may be the post void residual volume. In the case presented here that was about 200-300 ml. In the literature on cystocerebral syndrome there is usually urinary retention and a much larger volume - often 1 liter or more.

Until then BPH and the associated lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are markers that psychiatrists and sleep medicine specialists need to pay close attention

to - especially if it comes with insomnia, panic attacks and palpitations.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

References:

1: Fowler CJ, Griffiths D, de Groat WC. The neural control of micturition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 Jun;9(6):453-66. doi: 10.1038/nrn2401. Review. PubMed PMID: 18490916.

2: Griffiths DJ, Fowler CJ. The micturition switch and its forebrain influences. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2013 Jan;207(1):93-109. doi: 10.1111/apha.12019. Epub 2012 Nov 16. Review. PubMed PMID: 23164237.

4: Washco V, Engel L, Smith DL, McCarron R. Distended bladder presenting with

altered mental status and venous obstruction. Ochsner J. 2015 Spring;15(1):70-3.

PubMed PMID: 25829883; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4365850.

5: Saga K, Kuriyama A, Kawata T, Kimura K. Neurogenic bladder presenting with

cystocerebral syndrome. Intern Med. 2013;52(12):1443-4. PubMed PMID: 23774572.

6: Young P, Lasa JS, Finn BC, Quezel M, Bruetman JE. [Cystocerebral syndrome].

Rev Med Chil. 2008 Nov;136(11):1495-6. Spanish. PubMed PMID: 19301784.

7: Waardenburg IE. Delirium caused by urinary retention in elderly people: a case

report and literature review on the "cystocerebral syndrome". J Am Geriatr Soc.

2008 Dec;56(12):2371-2. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02035.x. Review. PubMed

PMID: 19093953.

8: Blè A, Zuliani G, Quarenghi C, Gallerani M, Fellin R. Cystocerebral syndrome:

a case report and literature review. Aging (Milano). 2001 Aug;13(4):339-42.

Review. PubMed PMID: 11695503.

9: Liem PH, Carter WJ. Cystocerebral syndrome: a possible explanation. Arch

Intern Med. 1991 Sep;151(9):1884, 1886. PubMed PMID: 1888260.

8: Blackburn T, Dunn M. Cystocerebral syndrome. Acute urinary retention

presenting as confusion in elderly patients. Arch Intern Med. 1990

Dec;150(12):2577-8. PubMed PMID: 2244775.

10: Glen W Barrisford GW, Graeme MS, Steele S. Acute urinary retention. O'Leary MP, Hockberger, RS Editors. UpToDate. Waltham MA: UpToDate Inc. http://www.uptodate.com (Accessed on March 30, 2018.)

Graphic Credits

Both neuroanatomy and urology graphics in this post are from reference 1 and posted here:

Reprinted by permission from Nature/Springer: Fowler CJ, Griffiths D, de Groat WC. The neural control of micturition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 Jun;9(6):453-66. doi: 10.1038/nrn2401. Review. PubMed PMID: 18490916. License number 4319020942759

The graphic of the empty sample cup is from Shutterstock per their standard licensing agreement.

10: Glen W Barrisford GW, Graeme MS, Steele S. Acute urinary retention. O'Leary MP, Hockberger, RS Editors. UpToDate. Waltham MA: UpToDate Inc. http://www.uptodate.com (Accessed on March 30, 2018.)

Graphic Credits

Both neuroanatomy and urology graphics in this post are from reference 1 and posted here:

Reprinted by permission from Nature/Springer: Fowler CJ, Griffiths D, de Groat WC. The neural control of micturition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 Jun;9(6):453-66. doi: 10.1038/nrn2401. Review. PubMed PMID: 18490916. License number 4319020942759

The graphic of the empty sample cup is from Shutterstock per their standard licensing agreement.

Sunday, March 25, 2018

Take Your Meds

"It might be because I have severe ADHD. It might be because it was jet fuel. I don't try to draw the line". - Stimulant user rationalizing use.

The above comment was made by a young man in the new Netflix documentary "Take Your Meds" about stimulant medications (but mostly Adderall). Fortunately or unfortunately depending on your viewpoint - physicians are still charged with the task of drawing the line. I don't typically like watching documentaries, but since this is my area of expertise I thought I would watch this one.

From the outset, it was apparent that the real downsides of using tremendously addictive drugs were not going to be emphasized. This was a sanitized version of abusable drugs. It was stated that prescription stimulant users were a class apart from methamphetamine users. There seemed to be an implicit message that in an egalitarian society - if the methamphetamine users had access to stimulants they would be better off. If we all could get access to performance enhancing drugs like stimulants the world would be a better place. A neuroscientist known for this kind of social commentary made some remarks basically stating that prescription stimulant use is another example of class factors in addiction. In this case because over half of the story was performance enhancement - that class argument was also made. Are those lower socioeconomic kids losing out because they don't have access to this performance enhancement? Probably not because the film makers don't present any data that performance enhancement actually occurs. It is the idea of performance enhancement.

A modicum of of common sense and medical use was introduced. They showed a very concerned pediatrician treating children of mothers who had some expertise in the field and nothing seemed to help their sons than stimulant medications. In one scene the pediatrician spends a time convincing one of these teenagers that it is up to him to take the medications. I do not know how doctors can have those conversations in awkward examination rooms with the unexamined identified patient sitting on an exam table and the doctor just standing there talking.

We meet a number of individuals over the course of the documentary. The first is a new college freshman. She is the first to comment the competitiveness/ performance enhancing aspect of stimulants - namely "Everybody here is on them. They are traded and sold. In order to be competitive I have to be on them."

We meet a former professional football player who starts taking them. We learn about how great he felt and how much of an advantage it seemed to make in all aspects of his play and in overcoming injuries. We learn that in the NFL, if you are a player you can get an exception to play with stimulants and take them if a doctor says that you have ADHD and then only the prescription written by the doctor. In this case the prescription was for Vyvanse 70 mg per day with 2-10 mg Adderall as needed on top of the Vyvanse. The Adderall was occasionally increased to 20 mg twice a day in addition to the Vyvanse. Either way he is taking more than the recommended total amount of stiumlant per day. One day before the game, the player in this case ran out of his usual stimulants and took Concerta (methylphenidate) from another player. Concerta had a different profile on toxicology screening and as a result he incurred a 4 game suspension. The details of what happens next are not clear but we see him when he is not longer playing professional football and has moved on with his life. In an interesting postscript, he talks about the conflict of being a different person on stimulants and what it means to take credit for what that person does.

We meet a Wall Street researcher and coder. We get opinions on what coders think of using stimulants to write code and their aspirations to write perfect code. He paints a picture of what it is like to work for a large investment concern. A room full of people on computers, expected to work very long hours and get rapid results. If additional time is needed, the plan is to take stimulants and get the work done. One night he declines stimulants, leaves work and the guy next to him stays there and at some point has a seizure from stimulants.

The common threads are the idea that stimulants are used as performance enhancers to be more competitive in academic and business environments. The idea is that every student and worker is expendable and if they can't do the job, somebody else will step up and do it therefore stimulants are necessary. Some seem annoyed by the charade of having to convince a doctor that they have ADHD in order to get a stimulant prescription. They would prefer just to get it without any medical diagnosis. Hallucinogens are brought up as additional performance enhancing agents - especially microdose hallucinogens.

There are the usual suggestions that this is a pharmaceutical marketing phenomenon. There is a brief discussion of America's first amphetamine epidemic and how the Controlled Substances Act was used to shut it down. The producers do mention that adult prescriptions for stimulant medications now exceed the prescriptions for children. They touch on problems with a totally subjective (first-person report) and a lack of clear objective markers for a diagnosis - but not the amount of fraud that goes on to get these prescriptions. Nobody ever points out for example, that none of these otherwise high functioning adults would qualify for the diagnosis on level of disability alone.

The only small bit of scientific data in the film was the work done by Farah, et al (1) who looked at the performance enhancing properties of amphetamines in health college students. Across a large number of neuropsychological variables it seems that the only one that was significantly improved was the persons perception of their performance. In other words, there was no objective sign that their performance was enhanced on cognitive testing but the subjects all believed they were performing better. There is more data that the performance enhancing aspects of stimulants are overblown.

That is certainly my experience interacting with amphetamine users for the last 30 plus years. I caught the tail end of the first epidemic and starting seeing obese patients on high dose amphetamines. Even though they had not lost a pound and were still very obese, they insisted on staying on high dose stimulants and were fearful they would gain weight if they stopped. In those days it was not uncommon to get a call to the Emergency Department because there was a narcoleptic patient there form another state who was taking high dose stimulants (> 100 mg/ day of amphetamines) for narcolepsy. My job was to figure out if the patient really had narcolepsy or they were lying to get stimulants.

Today my job is a little more subtle. Adults are operating from many levels of misconception about both stimulants and ADHD. Today I rarely meet an adult who does not think they have ADHD - even if they have a superior level of academic and vocational achievement. In some cases they have been swayed by the non-specific effects of stimulants - "I took my son's Adderall and for the first time I was able to focus and read well." In many cases they are influenced by professionals who have heard about the high heritability of ADHD and interpret this to mean if they diagnose a child with ADHD it means the parents and in some cases the grandparents have it. I have seen generations diagnosed this way. I work in the addiction field and everyone who is addicted to stimulants believes that they cannot live without them. They get quite angry if they are not supplied. That same population is in withdrawal form using very high doses of prescription or non-prescription stimulants and they also present with a residual ADHD that cannot be distinguished from ADHD but it is due to acute and chronic changes from stimulant overuse. Last but not last, the medical and potential medical complications of amphetamine use need to be carefully determined. Hypertension, cardiac changes, arrhythmias, and movement disorders are all fairly common in people who overuse stimulants.

These are a few of the major points that the Netflix documentary leaves out. It touches a few of the high points but like most media pieces it gets too focused on human interest stories. Historical lessons like what happened during the First Amphetamine Epidemic seem to be lost. When that ended in the 1970s even the rock bands of that era were sending the message that "Speed kills!" Addiction is more likely to happen if it is taken because for performance enhancement. Any time a person operates from the perspective that taking a medication will greatly enhance their performance, it is difficult to not think that "more is better."

If you are a bottom line person, I think you will be disappointed if you want to learn some science about ADHD and stimulant treatment in this documentary. You will hear a few sound bites but not much more. If your interest is more in the pharmaceutical industry selling stimulants and marketing them excessively, you will also get the superficial story. There is much more detail on annual prescriptions and trends. On a historical basis, I produced a timeline extracted from a history of America's first amphetamine epidemic that covers everything in the film and more without the film clips of Jack Kerouac. If you are an addiction specialist like I am, I think there is a message there that most of the prescriptions for adults are not for ADHD but for some type of cognitive enhancement and the basis for that is thin. That is a good take away message, but the real downside is not that apparent.

That downside is addiction. Compulsively using stimulants to the point that your life, your relationships, and your health are destroyed is as possible with prescription stimulants as it is with methamphetamine. Both are sold on the street by the same dealers. Contrary to what you read in the press or pick up in this film all it takes is exposure to amphetamines and the right genetic make-up to create an addiction. Having true ADHD, or the right socioeconomic standing, or willpower doesn't protect you against addiction. Once an addiction to prescription or nonprescription stimulants occurs it is a very difficult problem to recover from. Unlike opioids and alcohol - there are no known medications to assist in recovery.

So like most treatments in medicine, stimulants need to be cautiously applied. Indiscriminate use for performance enhancement does not seem like a good idea to me because it will cause proportionally more addiction and the cognitive gains across the population are minimal mostly restricted to the perception that you are doing much better than you are.

Not a good reason for taking stimulant medications unless you really need them.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

References:

1: Ilieva I, Boland J, Farah MJ. Objective and subjective cognitive enhancing effects of mixed amphetamine salts in healthy people. Neuropharmacology. 2013 Jan;64:496-505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.07.021. Epub 2012 Aug 1. PubMed PMID: 22884611.

2: Smith ME, Farah MJ. Are prescription stimulants "smart pills"? The epidemiology and cognitive neuroscience of prescription stimulant use by normal healthy individuals. Psychol Bull. 2011 Sep;137(5):717-41. doi: 10.1037/a0023825. Review. PubMed PMID: 21859174

Sunday, March 18, 2018

More On Takotsubo

I posted previously on Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and an association with antidepressant therapies. That occurred in the context of a patient with the condition that I recently treated. At times when there is a condition that is prominent on your mind and you tend to notice it immediately as you review the literature. In this case I noticed it in the New England Journal of Medicine as this weeks Case Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. If you plan on reading the case - please do that first before reading the summary that follows. Like most of these cases it is a textbook description of the way experts should think about complicated diagnoses. I will naturally focus on what I think are the high points for psychiatrists.

The patient described was a 55- yr old woman with a history of thyroid cancer but no other chronic illnesses. She had a history of Stevens-Johnson syndrome from cefadroxil. She was did not smoke, drink, or use other intoxicants. She was married and employed. Four months before the index episode she was jogging and had pounding in the chest, diaphoresis, and nausea for about 40 minutes. She was seen in a local ED and a mildly elevated troponin [0.055 ng/ml] that increased at 11 hours 0.415 ng/ml] , 4 normal ECGs, normal echocardiogram, and normal coronary angiogram. A subsequent MRI scan was done and was normal. The presumptive diagnosis was exercise related supraventricular tachycardia. She was prescribed a beta blocker and ASA and discharged.

She resumed jogging and eventually stopped the beta blocker. Four months later while skiing, she developed palpitations, dyspnea and weakness. she was assisted off the mountain, but developed nausea, emesis, chest pain, and shortness of breath. In the local emergency department she was tachycardic, tachypneic, and normotensive. Her oxygen saturation was 84% on room air. Troponin I [11.000 ng/ml] and N-terminal- pro-B-type natriuretic (NT-proBNP) [15,159 pg/ml] levels were elevated. Bedside cardiac ultrasonography showed severe left ventricular dysfunction with apical ballooning. She was transferred to a tertiary care center for suspected cardiogenic shock. At that center she was noted to be critically ill and received all of the measures necessary to treat the shock including mechanical ventilation and pressors alternating with antihypertensive treatment episodes. A left ventricular assist device (LVAD) was placed. She was subsequently transferred to MGH.

There she was noted to need continued need for treatment of heart failure. Infectious agents for myocarditis were ruled out. Femovenoarterial extracorporeal life support was added to improve cardiac output and also because the LVAD was causing significant hemolysis. The patient's cardiac status improved on day 3 and an endomyocardial biopsy was done when the extracorporeal life support was removed. That biopsy was consistent with myocardial injury, myocardial toxicity, mechanical stress and treated myocarditis. Acute myocarditis was ruled out.

A clinical diagnosis of takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy was made. A consultant discussed the limited differential diagnosis of apical ballooning not associated with coronary artery disease and the associated etiologies as:

1. Recurrent apical ballooning syndrome

2. takotsubo cardiomyopathy

3. Acute myocarditis

4. Coronary vasospasm

5. cocaine induced coronary vasoconstriction

6. thrombosis with endogneous fibrinolysis before angiography

Several etiologies (1,2,5) may depend on similar hypersympathetic mechanisms caused by exercise, neuropsychiatric disorders, psychiatric medications, or intoxicants causing catecholaminergic effects. Takotsubos was described as an increasing cause of acute non-ischemic cardiomyopathy in patients admitted with acute chest pain syndromes. In one series the disorder accounted for 7.5% of all admissions with acute chest pain. Eventually the patient is diagnosed with pheochromocytoma as the cause for takotsubos, the adrenal tumor is resected, she regains normal cardiac function and her recovery is uncomplicated. The staff at MGH has done another outstanding job of solving a complex medical problem and saving a crtically ill patient.

How does all of this apply to psychiatrists? I am sure that there are some people out there who are irritated just to see a psychiatrist talking about medicine. Well I will tell you:

1. Cardiotoxicity of catecholamines:

I think we have been lulled into thinking that anxiety and even panic attacks won't kill you so why worry about that patient with elevated vital signs or persistent tachycardia that won't go away? Granted - very few of those people will develop takotsubos and even fewer will have a pheochromocytoma. I have treated several people with takotsubos and none with a pheochromocytoma - so if I had to guess I would say the cardiomyopathy is much more common in clinical practice. Once you know that vitals signs (including pulses) need careful monitoring and caution needs to be exercised if medications are being added that might add to the catecholaminergic burden.

Over the years I have encountered very many patients with persistent tachycardia and otherwise normal electrocardiograms showing sinus tachycardia. The general sequence of events at that point it to assess for causes of the tachycardia and obtain Cardiology consultation to look for inappropriate sinus tachycardia and suggest treatment if that condition is found (2). Persistent tachycardia can lead to left ventricular hypertrophy and cardiomyopathy but that is typically rare.

I have discussed these cases with many Cardiology consultants who tell me that sinus tachycardia is "not normal" there are just no guidelines about what to do about it, especially if there is no obvious cause. Using beta-blockers just to treat tachycardia seems like an arbitrary decision on their part based on whether the patient experiences any distress from palpitations. Psychiatrists use beta-blockers for the same indications as well as the physical manifestations of performance anxiety.

2. Monitor vital signs, troponins and get timely Cardiology assessments:

You might find yourself in an environment where you have to go the extra mile to get help from medicine or cardiology. I found myself in a situation with patients who had chest pain and instead of transfer to medicine the decision was made to keep the patient on the psychiatric unit and measure troponins. That is the main reason I included the troponins in the above summary. Even the mildly elevated and trending higher troponins may be an indication of some type of milder myocardial damage. It might even be useful to discuss with the consultant that takotsubo might be a consideration.

3. Potential risk factors for takotsubos should be considered in all patients who are assessed:

From the list in the differential there are a wide range of catecholaminergic insults that psychiatric patient may incur including prescription and street stimulants (amphetamine, methamphetamine, cocaine, synthetic cannabinoids, JWH compounds, synthetic psychedelics), antidepressant compounds and atomoxetine, intoxication and withdrawal states (3), sleep deprivation, seizures (4) and physiological factors like extreme physical or emotional distress. It is very common to see one or more of these factors present during patient assessments and in that case, a cardiac review of systems should be done. I am cautious to not start a new drug with potential cardiac side effects until sinus tachycardia has resolved.

4. A diagnosis of takotsubos needs to be considered in the discharge plan:

In today's treatment environment of getting people out of the hospital as soon as possible or not admitting them in the first place acute stress induced cardiomyopathy takes on a different meaning. In the NEJM case, the patient had the unexpected burden of catecholamines from a pheochromocytoma that had obvious toxicity on cardiac function and she recovered uneventfully once definitive treatment was completed. What if you are a treating psychiatrist and you know your patient has this diagnosis? The decisions that need to be made include discontinuing any potentially toxic psychiatric medications and preventing damage from other sources of catecholamines. This is relevant if it is highly likely that the patient will be in a stressful environment or is highly likely to use some of the toxic medications. The discharge plan needs to be modified accordingly.

That is my proactive approach to sinus tachycardia and takotsubos when it is identified. It should be apparent that I do not take a passive stance when it comes to potential medical problems in my patients, especially when it directly affects psychiatric care and the recommended treatment plan. You don't have to be an expert in ECG or managing complex cardiac conditions but you do have to recognize when your patients health status is compromised. Saying that there has been "medical clearance" by another physician is not enough. This approach does help define the medical skill set that every psychiatrist needs to possess. In these cases knowledge of basic cardiac conditions, basic ECG skills, and how the medical and psychiatric treatment plans need to be modified is a requirement.

George Dawson, MD, DFAPA

References:

1: Loscalzo J, Roy N, Shah RV, Tsai JN, Cahalane AM, Steiner J, Stone JR. Case 8-2018: A 55-Year-Old Woman with Shock and Labile Blood Pressure. N Engl J Med. 2018 Mar 15;378(11):1043-1053. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc1712225. PubMed PMID: 29539275.

2: Homoud MK. Sinus tachycardia: Evaluation and management. Piccini J Editor. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate Inc. http://www.uptodate.com (Accessed on March 18, 2018.)

3: Spadotto V, Zorzi A, Elmaghawry M, Meggiolaro M, Pittoni GM. Heart failure due to 'stress cardiomyopathy': a severe manifestation of the opioid withdrawal syndrome. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2013 Mar;2(1):84-7. doi: 10.1177/2048872612474923. PubMed PMID: 24062938.

4: Kyi HH, Aljariri Alhesan N, Upadhaya S, Al Hadidi S. Seizure Associated Takotsubo Syndrome: A Rare Combination. Case Rep Cardiol. 2017;2017:8458054. doi: 10.1155/2017/8458054. Epub 2017 Jul 24. PubMed PMID: 28811941.

Graphics Attribution:

"Levocardiography in the right anterior oblique position shows the picture of an octopus pot, which is characteristic for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy."

Hammer N, Kühne C, Meixensberger J, Hänsel B, Winkler D. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy - An unexpected complication in spine surgery. Int J Surg Case Rep (2014). Link Used per open access license.

Conventions:

There does not appear to be a consensus on the spelling of takotsubo and whether or not it should be capitalized or not.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)